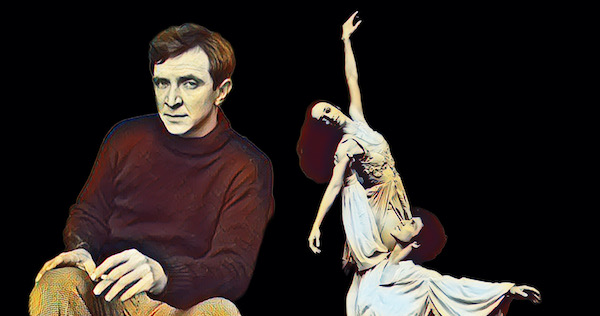

50 years ago, when choreographer John Cranko died suddenly at the age of 45, the dance world prematurely lost one of its most talented and promising creators. At the time director of the Stuttgart Ballet, Cranko transformed the small German company into one of the most renowned ballet houses in the world. As a young man, he had a seemingly bright future ahead of him, but when he collapsed on a flight from Philadelphia to Stuttgart, it all ended.

Just two days before that June 26, 1973, the Stuttgart Ballet was on its third American tour, having performed its version of Swan Lake in Philadelphia. It was the most talked about dance company at the time and everyone’s proposal was to take a vacation, so much so that her muse, friend, and star, Márcia Haydée had already landed in Rio de Janeiro when she received the news. The aircraft chartered by the company made a scheduled stop in Dublin, where Cranko, who had taken a sleeping pill and did not wake up, was pronounced dead on arrival at a hospital. The cause of death was a heart attack.

John Cranko was born in South Africa, and, according to his biographers, he always wanted to choreograph, learning to dance to have the means to achieve his goal. Informal, chain-smoking (he always had a cigarette in his hands) he was idolized by his dancers. Alongside Kenneth McMillan, Cranko was a choreographer who was modernizing dance, not getting stuck in recreating classics, but releasing completely new ballets. To understand what this meant, 18th and 19th-century ballets were always “complete” when they brought a plot to drive the dance. George Balanchine left this aside when he went to the United States, creating the “symphonic ballets”, small pieces without big sets or stories to lead, using only the music to lead the steps. John Cranko did not stick to this “modernity”, he created new ballets such as The Taming of the Shrew and Oneguin, to name just two of his contributions.

“As a choreographer, Mr. Cranko took the risk of reviving the full-night ballet at a time when most audiences favored plotless one-act work. It was a gamble he won,” wrote NY Times critic Anna Kisselgoff, who signed his obituary and quoted a 1969 interview with the artist in which he explained, “I don’t see why ballet shouldn’t be entertainment. , but it should be more than entertainment. There is the challenge of making a ballet work on two levels – as a dance and as a story.”

And it was as a great storyteller that he was always remembered. Having studied at the Royal Ballet and worked with Sadler’s Wells Theater Ballet since leaving South Africa, having to make his way with a company that had legends like Frederick Ashton still in business, John Cranko realized he would have to look elsewhere for opportunities to grow. , so it was a bit of a surprise that people led with the news that he had accepted to become ballet director in Stuttgart, at the Wiirttemberg State Opera. No one knew about the company’s capacity, but he knew that there would be space and creative demand there, after all, at the Royal, he was lucky. create a ballet every year and a half. Within a few years, the names of Cranko and Stuttgart were not only known worldwide but revered as well.

The 1960s were years of glory for him, who survived the harsh divorce of his parents by creating theater plays with his toys, until, at the age of 14, he discovered dancing. He took ballet classes at the University of Cape Town (where he choreographed his first pieces) and in 1946 entered the school of the Royal Ballet, then Sadler’s Wells Ballet, being among the founders of Sadler’s Wells Theater Ballet. Creating was his goal, he didn’t stand out as a dancer and as soon as he could, he started choreographing.

While at the Royal, he did not have good results with his ballet The Prince of Pagodas, but it was when he reassembled it for the Stuttgart Ballet that he established the link that would change his life. The following year he was invited to head the company.

Her version of the ballet Romeo and Juliet made two years before Kenneth McMillan’s popular production for the Royal, is considered by many to be one of ballet’s most creative works, having gained more prominence in recent years.

John Cranko‘s great muse was undoubtedly the ballerina Marcia Haydée, for whom he created his most iconic works and with whom he worked until her death. “The day before I auditioned for the Stuttgart Ballet, he was teaching a class, which was very strange, because he did choreography in class, it wasn’t a normal class. So at one point, he said, ‘Do this,’ and nobody did anything, and I raised my hand and said, ‘I think I know how to do it. And I let go like crazy. Later he told me that it was at that moment that he saw that I understood him. The next day, I auditioned for the corps de ballet, I rehearsed a part of The Sleeping Beauty and after dancing he went up on stage and told me to wait for him in the dressing room. Upon arrival, he said: ‘Marcia, I will not hire you as a corps de ballet, you won a contract as a prima ballerina’. I think that moment was pivotal in my life,” she commented in an interview two years ago.

With the 50th anniversary of his death approaching, it is always time to remember John Cranko’s genius and be grateful that his works contributed to the immortality of dance.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.