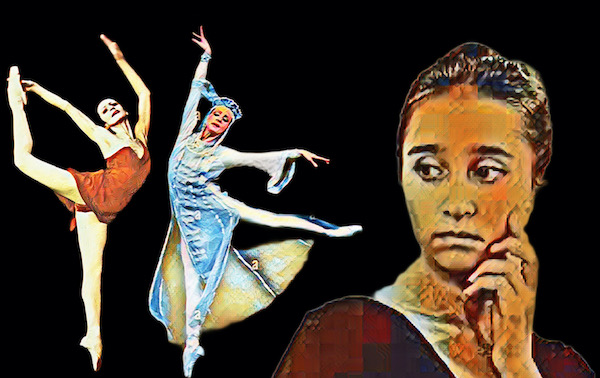

My admiration for some of the dancers who were top stars when they were still dancing is natural. Among them, I had the privilege of seeing the great Natalia Bessmertnova twice on stage, immortalized by films that lived up to the meaning of her last name: Immortal. Natalia was the muse of her husband and choreographer, Yuri Grigorovich, so she starred in some of her greatest works, including Spartacus and Ivan the Terrible. I saw her dancing both live, in Rio and Paris, I have the privilege. And in the year that completes 15 years of her death, I pay a brief tribute.

Natalia Igorievna Bessmertnova was born in Moscow on July 19, 1941, at the beginning of the Second World War, therefore in particularly difficult times, marking her childhood and bringing determination and compassion, and empathy that marked her personality from an early age. Daughter of a doctor, she was of reasonable social standing, she began her dance training at a very young age, at the Palace of Young Pioneers in Moscow, before entering the Bolshoi school in 1952.

She graduated at the age of 20, but there are conflicting accounts of her background. There is a version that her training period was far from suggesting that one day she would be one of the biggest stars of the company, with a history of fragile health, getting sick and getting injured frequently, in addition to being identified as slow to assimilate her studies. And then there’s the fact that in just nine years she graduated as the first student to earn the highest possible grade: A-+.

Putting the two together reinforces the legend that little Natasha only revealed what was hidden in her a year before graduation, in performances known as “graduation concerts”, when she technically stole the show and left the other graduates ‘erased’ in comparison. Once ‘revealed’, the rise was meteoric. In 1963, just two years after joining the Bolshoi Corps de Ballet, she debuted in her signature role, Giselle. From then on it was just success.

In her early years, personally coached by the legendary Marina Semyonova, Natalia focused on traditional classical repertoire, shining as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake, Raymonda, Aurora in Sleeping Beauty, and Kitri in Don Quixote. She often danced with Mikhail Lavrovsky and Yuri Vladimirov and conquered the West as the Bolshoi traveled to Europe and the United States.

The lightness of her dance and the docility of her person was clear in all of her roles, as well as her long arms, legs, and large black eyes. He was a magnet when she was on stage. But she also had a unique elasticity, lift, and strength that always surprised her, conveying a wide spectrum of emotions, as an actress too.

It was at the Bolshoi that she met her husband, Yuri Grigorovich, who was already a prominent choreographer and would later become the company’s artistic director. It wasn’t love at first sight, it seems. They say that when she first saw him, she didn’t recognize him, she just thought he looked weird and funny. It was her best friend, Nina Sorokina, who explained who he really was. Once in love, naturally, like her muse, Natalia went on to star in the biggest productions with which she was forever associated. Grigorovich knew how to bring out the best in her and created the roles of Shirin in Legend of Love and Phrygia in Spartacus for her.

It couldn’t have been easy dealing with backstage jealousy, especially since she was the one who inherited the repertory roles of Russia’s biggest star, Galina Ulanova when she retired. None other than Maria in Fountain of Bakhchisarai and Juliet in Leonid Lavrovsky‘s Romeo and Juliet. Legend has it that Natalia herself told the story of how, shortly after marrying Grigorovich, Maya Plisetskaya entered her dressing room and said: “It won’t work. He’ll leave you in a year.” The 40 years of marriage proved that it was true love. Only death separated them. Friends of hers also defend her from references to being in the shadow of her husband’s genius when they call her just a muse. In fact, witnesses say that she directly helped him create the steps, which is why she is so visible even when others dance that her soul is in the ballet.

Natalia’s success was also in staying in traditional roles, keeping her Giselle as one of the biggest references, being physically compared to two legends, Anna Pavlova and Olga Spessivtseva. Before leaving the Soviet Union, Mikhail Baryshnikov, who was Kirov, danced as Albrecht alongside her. It was her last performance with Kirov (Mariinsky), on April 30, 1974.

For me, Natalia’s best role, as well as Grigorovich’s ballet, is Ivan the Terrible from 1975, where she created the role of Tsarina Anastasia. The last collaboration of an original ballet by the two was in 1982, where she played Rita in The Golden Age. At her side was the young Irek Mukhamedov, with whom I saw her dance Spartacus on the Bolshoi’s first tour of South America in the 1980s.

Natalia retired from the stage in 1995 (four years after I saw her in Paris). It was a period in which many dancers resented Grigorovich’s (long) tenure and a time when backstage conflicts took the media stage. Natalia remained in support of her husband, accompanying him to other companies and dedicating herself to training new talent. She died in Moscow on February 19, 2008, after battling an undisclosed “long illness”. She was 66 years old. She left a legacy of iconic interpretations and an example of professionalism and companionship. Here, my eternal admiration for her.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.