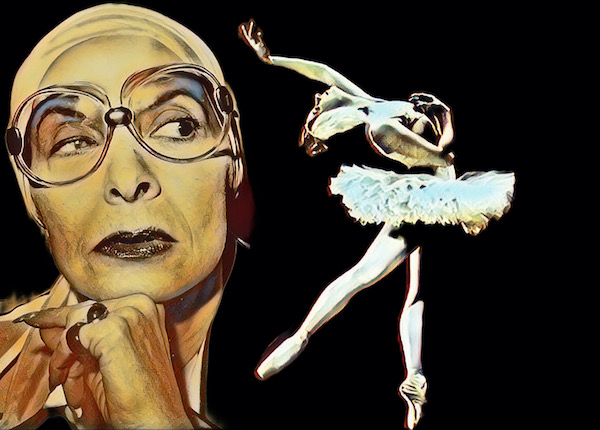

In October 2019, one of the biggest names in the History of Dance – Alicia Alonso – passed away at the age of 98, from what was described by Cuban TV channels as a “cardiovascular disease”. Alicia, who left a career of maximum stardom in the United States to return to her country in 1948, supporting Fidel Castro‘s Revolution, was a worldwide dancer. Her story would lead to a series and films, and I hope they still do her justice.

Alicia Alonso was one of the few considered ballerina assoluta, a title associated with virtuosos and icons. Even blind, she danced for many years, moving everyone with her perfection and dedication.

“I dance inside myself, with my eyes closed,” she said. Ours were always wide-eyed when faced with her Art.

At age 20, a Cuban woman in New York

Born “on the outskirts” of Havana, in 1920, Alicia was the daughter of a seamstress and an army vet lieutenant. Due to her father’s position, she lived at a very young age in Spain, where she studied flamenco and even learned to play castanets, before starting to study ballet at the age of eight, when they returned to Cuba. “When I was little, whenever I heard music I moved, maybe like Isadora Duncan, because I didn’t know what it was to dance” she once said.

She immediately revealed a natural talent for ballet and, signing as Alicia Martínez debuted on stage in the traditional Sleeping Beauty, aged just 11. Her love of dance set her on the path to her first husband, her classmate, Fernando Alonso, with whom she fell in love and whom she married when she was 16 and began using her married name.

The two then moved to New York, seeking more opportunities in the United States, since there was no ballet company in Cuba. While Fernando, who would later be a renowned choreographer, continued dancing, Alicia divided her time between ballet classes and rehearsals, as well as taking care of her daughter, Laura, born in 1938. Her professional debut in America was as a chorus girl in musicals on Broadway, who helped support a young immigrant family.

As she was a virtuoso, it didn’t take long for Alicia’s talent to be identified. At just 20 years old she was recruited into the newly formed American Ballet Caravan, later the New York City Ballet, and was immediately cast in leading roles. George Balanchine created the difficult Theme and Variations for Alicia and her partner, Igor Youskevitch, a ballet still danced around the world.

Backstage was confusing, with the dancer and her partner wanting a story and the choreographer insisting they follow the steps and the music. On one occasion she even said that Balanchine created complex steps to “eliminate their personalities”.

“I remember Mr. B. looked at me and said, ‘Can you do this step?’ which was nothing less than an entrechat six, a jump straight into the air with quick leg crossings. ‘Are you scared?’ he asked and I replied, ‘No, no. I’ll try, Mr. Balanchine.’” Of course, he did.

Other classics that were created based on Alicia were Undertow, by Antony Tudor, and Fall River Legend, by Agnes de Mille.

Because she wanted to dance the great classics, Alicia left Balanchine in 1941 to join the cast of Ballet Theater (later American Ballet Theatre). It was there that the legend of Alicia Alonso began to be written, with unsurpassed interpretations of Giselle and Swan Lake.

The vision problem and overcoming it

Alicia Alonso started having problems when she was on stage. Flashing lights and dark spots crossed her vision, hindering her movement. She decided to investigate and the bombshell came: she was diagnosed with severe retinal detachment. Her ballet career would have to wait.

The following two years were marked by three major eye operations that required absolute rest. Her dream was to dance the role that would become her signature, Giselle, and, even in bed, she memorized the steps in her head and practiced them with her fingers on the sheet.

The diagnosis after all the sacrifice was not encouraging. Not only would she never regain her peripheral vision, but what she had would progressively deteriorate. She would go blind at a young age and the best thing would be to retire her sneakers. Something that Alicia Alonso simply refused to accept.

In 1943 she returned to the Ballet Theater and danced her first Giselle, replacing the great Alicia Markova. The audience went down with her interpretation.

For no less than the next four decades, the dancer continued to disobey the doctors, without stopping dancing. As her vision worsened, she began using specially positioned lights to guide her on stage, also relying on the help of her partners who whispered directions to her.

On stage, in addition to being a great actress and having unique musicality, Alicia Alonso also had almost masculine strength and control, both in her equilibriums and pirouettes. In short, it was incredible.

Return to Havana

In times of World War II, it was only natural that the Ballet Theater would experience temporary financial problems, but Alicia took the chance to return home.

The dream, soon realized, was to found her own company, Ballet Alicia Alonso, with several dancers from Ballet Theater and staging the traditional Swan Lake and Giselle. This air bridge between Havana and New York became Alicia’s reality, supporting the company with Fernando as general director, and his brother, Alberto, as choreographer and artistic director.

Alicia Alonso‘s name would be aligned with international politics when, in 1959, Fidel Castro came to power. He invited her to transform her company into Ballet Nacional de Cuba and the ‘yes’ was immediate. With the support of the Dictator, Cuba became a world center for classical ballet.

Alicia’s project was even bigger: she would discover and train new local talent, and to do so, she toured cities and villages looking for candidates. The fact that through ballet they would have financial support, food, and the opportunity for a prestigious career, helped to spark an immediate interest in the dancer.

Tyrant?

In fact, over the next four decades she ‘discovered’ some of ballet’s greatest talents: Fernando Bujones, Jorge Esquivel, José Manuel Carreño, and Carlos Acosta are some of them. The Cuban National Ballet is still one of the most respected dance companies today, thanks to Alicia.

Of course, her connection to Fidel Castro also generated criticism, especially after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, because Cuba remained ‘closed’ and isolated, and so did Cuban ballet. As the company’s founder, and its main star, the dancer’s management quickly went from being firm to authoritarian. Her external popularity was not always in line with internal criticism.

Alicia danced until she was 70, reserving the best roles for herself. Yes, she danced Giselle until she departed from the stage, and many claim that, out of personal pride, she limited the careers of dancers who threatened her own fame. This combination led to the desertion of many young people, such as Carreño and Lupe Serraño, who went to ABT, and Acosta to the Royal Ballet. It was only close to her death, in 2019, that Alicia ‘flexed’, appointing Viengsay Valdés as her deputy artistic director.

Even during the Cold War, she was idolized

With the Cold War and its association with communism, it was expected that Alicia Alonso’s name would arouse rejection, but no. Her talent was so inspiring that she was idolized and honored inside and outside Cuba, and all over the world.

For example, in 1975, the greatest legends of classical dance gathered on stage in honor of the prima ballerina assoluta, names such as Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolf Nureyev, Márcia Haydée, Gelsey Kirkland, Fernando Bujones, Margot Fonteyn, Cynthia Gregory, and Erik Bruhn. Unsurprisingly, in Russia, ‘sister political regime’, there was an exchange between dancers, with Alicia and Maya Plissetskaya playing Carmen and Vladimir Vassiliev being her partner in Giselle, as two examples.

The Cuban National Ballet’s visit to Brazil, in the early 1980s, was one of the most publicized events in the country at the time, with Alicia receiving a standing ovation on stage.

Farewell to the stage at 70

With the loss of her vision, it was expected that Alicia would have shortened her time on stage, but dancing was her reason for living and she danced until she was 70, with several images of her technique in Giselle taking one’s breath away.

In her personal life, her dedication and firm commitment to the company also took its toll. Historians comment on her possessiveness from the beginning regarding the main roles, insisting on dancing them herself. In addition to the dancers, this created problems with her husband, with whom there were already other conflicts and they divorced in 1975. Alicia subsequently married Pedro Simón, a dance critic, editor, and philosophy professor who was also co-executive director of the company and became known as the wife’s “eyes”.

The news of Alicia’s death, two years before her 100th birthday, shouldn’t have, but it took the world by surprise. Perhaps she was to ballet what Queen Elizabeth was to the world: a symbol of constancy. But eventually, just human.

Her unique legacy in dance, however, is unparalleled. Her commitment to Art, dancing despite her blindness, and being a perfectionist and idealist, literally make her a legend. Furthermore, she was technically superior to many today. Her words serve as an inspiration to everyone, inside and outside of dance: “I sought perfection every day”, she said, “and I never gave up”.

Five years after her death, it is worth remembering her with the same passion she aroused in life. Absolute as her title.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.