Throughout the Ripley series, as well as in the book and film The Talented Mr. Ripley, Tom Ripley (Andrew Scott) has two antagonists who are never wrong with him: Freddie Miles (Eliot Sumner) and Marge Sherwood (Dakota Fanning), the best friend and girlfriend of Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn). So it’s easy to understand Ripley’s distaste for her, but what about the others?

Yes, Dickie’s father, Inspector Ravinni (Maurizio Lombardi), and practically all the men in the series are a bit of an irritant to Marge, without taking seriously what she’s been warning her all along that something wrong happened on San’s trip. Remus and that Dickie just didn’t disappear. It is blatant and even frustrating misogyny as it also reflects how independent women are judged and ignored. Dickie lost his life and fortune (I’ll talk more about him later), but one of Tom Ripley’s main victims is Marge Sherwood, who suffers gaslight when she is discredited and manipulated into believing that she “lost” her boyfriend because she is a woman and has him away from her by demanding a series of things that we know are justified. Still, why don’t they sympathize with Marge?

Who is Marge Sherwood?

We meet Marjorie Sherwood, known as Marge when Ripley arrives in Italy and introduces herself to Dickie Greenleaf. The American scammer was hired by the countryman’s father to locate him and bring him back to the United States (he doesn’t explore it in the series, but it was because Dickie’s mother was dying of cancer).

In theory an easy and well-paid job, but everything changes when Ripley meets Dickie and is enchanted by everything: his personality, his fortune, his careless sophistication, his indifference to his family (he solemnly ignores his parents’ plea), his passion for Art (even if he has no talent of his own) and his plans to live a hedonistic life. The only thing that clashes with him is precisely his girlfriend, Marge, with whom Dickie maintains a relationship without any major plans and therefore apparently disposable.

Marge in the book, the 1999 film, and the series differ greatly, another sign of how she is relegated to a supporting role no matter the medium. An expatriate like Dickie, she imagines herself an Ernest Hemmingway in skirts, an everyday writer and amateur photographer. Yes, she writes poorly, but she is an excellent observer of scenery and people: her lens takes beautiful photos of Italy and Dickie and she is never wrong with Ripley, although she never achieves the accuracy of her instinct.

A detail that is not overlooked by foreigners and that makes all the difference in understanding what causes male reactivity to Marge, a beautiful and intelligent girl, who is worth remembering. Firstly, she is not rich like Dickie, she comes from the interior of the United States and has a simpler house, separate from her boyfriend. In other words, she is a modern woman.

In the 1950s, when the story takes place, no woman should have been like this. They were all created to get married and have children, to be a gift and a home. Marge is the opposite. She doesn’t demand a commitment from Dickie (yes, fidelity, but not being Mrs. Greenleaf), she doesn’t tidy her house, she leaves her underwear visible on the line, scattered around the house, she doesn’t wash the dishes or go shopping. She lives as carelessly as Dickie, who, unlike her, has a servant wife who pays her to take care of everything for him.

This characteristic of Marge is not what author Patricia Highsmith wanted to highlight. She is partial to her beloved Ripley and clearly harbors in him her own dislike of the only prominent female character in the story. That’s right, Marge is not Patricia’s alter ego.

To Dickie’s father, Marge is an opportunist hoping to secure a marriage with him. As far as she knows, and it is never clear, it is under “her” influence that the son is far away, the problem is never with the man, it is always the woman who defines everything. And for Ravinni, who doesn’t think much differently, Marge is a jealous and paranoid girlfriend, someone Dickie wanted to get away from (an idea planted by Ripley).

I have a special sympathy for Marge, I feel sorry for her living in the time she did. And when Ripley gaslights her by blaming Dickie’s “suicide,” my heart broke because she believed it.

Therefore, as Dickie’s on-again, off-again romantic interest and Tom’s main rival for his affections, Marge Sherwood plays multiple women. She is intelligent, educated, and kind, but because she is in love with Dickie, she allows herself to be treated unfairly at the hands of him and those around him.

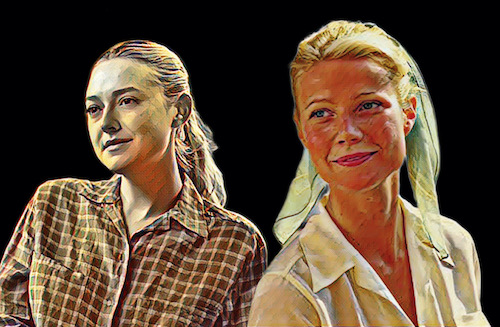

Dakota versus Gwyneth

A child actress who made a great transition to adult roles, Dakota Fanning had a shadow for more recent audiences who did not yet know the Tom Ripley created in 1955. The most recent – and beloved – was in Anthony Minghella’s 1999 film, with a Gwyneth Paltrow at the height of her career (and recent Oscar winner). Smartly, Dakota chooses

I have another path for the character, but the comparison is inevitable. And unfair.

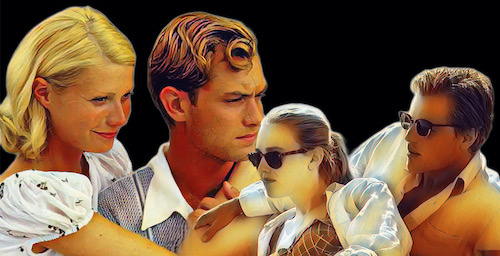

In the Oscar-nominated film 25 years ago, Gwyneth Paltrow‘s Marge is a rich, sophisticated young woman who is part of Dickie’s social circle. Sweet and affectionate, she is completely in love with her boyfriend, choosing to ignore his flirtations, not identifying anything wrong with Tom Ripley, on the contrary, being the person who hugs him and translates the facets of Dickie and his friends, including Freddie Miles.

In Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, Marge doesn’t catch the gay vibe between Dickie and Tom, she only realizes that something is wrong when she is abruptly excluded from her boyfriend’s life (who was murdered by Ripley) and that’s when she develops distrust and irritation with the psychopath. Gwyneth’s Marge has a sadder ending: she KNOWS the truth but is considered crazy and needs to keep quiet, as she has no way of proving anything.

The Netflix version of the series is less sympathetic to Marge, with a Dakota Fanning sort of mirroring her rival for as long as she’s known him. Mutual distrust is fueled by long silences and exchanges of glances between her and Andrew Scott, sometimes with more chemistry than between her and Johnny Flynn, who is Steve Zaillain‘s Dickie. Johnny played a mysterious millionaire, aware of his artistic limitations but very comfortable with where he wanted to live. He doesn’t love Marge like she loves him, that’s the same, but he’s more devoted to her than the peerless version of Judd Law, who more credibly fuels the competition between her and Ripley for his affections.

Dakota’s Marge is more assured than Gwyneth’s, openly defying Andrew Scott‘s Ripley. She is not even shaken by the “danger” of Freddie Miles’ influence wanting to take Dickie to an exaggerated Christmas, she is only irritated by Tom’s constant and inexplicable presence among them.

The placidity with which Marge deals with everything, even Dickie’s disappearance, waiting for him and only communicating via letters (how did she not pick up on the different writing style?) is somewhat disconcerting. After all, she had warned her boyfriend to cut Ripley out of their lives, but she became strangely quiet when Dickie started defending Tom and ghosted her for the rest of the series. Ripley’s manipulation is distressing and he finally wins the game, convincing Marge of the lie: he was superior to her and Dickie killed herself for him. Very cruel.

What hurts about Minghella’s version, and partly about the Netflix version, is that Dickie was aware that he didn’t love Marge, but in both productions he was determined to join her, to try a relationship that was only good for him. Tom Ripley took that possibility away from both of them out of greed and envy. A tragic twist of fate never revealed to anyone but us.

Marge versus Ripley: the love of good things and fame

In Ripley there is a somewhat mean-spirited allusion that Marge comes to appreciate the media attention on her and that she uses her connection with Dickie to sell photos, promote herself and even write her book. She wants to find him but never considers anything more serious about leaving her until she finds the ring in Ripley‘s things. And there, like many women, she volunteers the theory that she “pressured him too much”, “demanded things she shouldn’t have”, “waited too long” and more, that she “didn’t see” that Dickie was gay, so he killed himself “because of your fault”.

Would it be narcissism or the eternal female guilt of having to be the person to save everyone and solve everything? The lack of empathy for this conflict among so many women is one of the regrets of the work because even though it is a supporting role, it is vital to create antagonism with Ripley.

In the words of Patricia Highsmith, Tom Ripley feels threatened by the “feminine touch” that Marge represents in Dickie’s life. He is repulsed by her, but cannot dismiss her without drawing attention to the fact that he is directly involved with the murder and the mystery surrounding the young American millionaire.

Marge, in the book, is one of the symbols of Tom’s disdain for anyone except himself and Dickie. Above all, she represents the society that determines heteronormative attraction as a rule and with that, female attraction to men, with the “weapon of their sexuality” that Tom, never without admitting to being homosexual, hates.

Dakota doesn’t convey naivety to Marge, what she lacks is a wickedness of soul that would make her see Ripley’s true monstrosity. Just like us, for her it is quite incompressible that Johnny Flynn’s Dickie, even though he knows that Tom lied when he introduced himself and that he is being paid to take him to New York, accepts his presence in his home for an indefinite period, dedicating himself to he spent more and more time than he allocated to her.

She sees Tom clearly, sees that there is romantic hope in his extended stay, and soon feels jealous and resentful of having to share her boyfriend with him. Here’s one thing I disagree with about the series. Marge seems afraid that Dickie – who he knows doesn’t like her like she likes him – will get involved with Tom. I would understand that she would be jealous and afraid of the influence Ripley could have on Dickie finding other women, not leaving her for Tom.

Even in the scene in which she seems to enjoy being photographed by the paparazzi, I considered the judgment that she was also indirectly taking advantage of Dickie to be unfair, but that kind of remains up in the air with this suggestion. Could Marge be Ripley’s female mirror?

As I already mentioned, with privileged access to Dickie’s masculine thoughts, who admits to Tom that he ‘likes’ Marge but sees no future between them, Tom is convincing in making Marge believe that she is being ghosted by her boyfriend while he suddenly decides to stay alone for a while to rethink their future. It’s pure gaslighting from Ripley. And so effective that she is the one who finds the solution to the case: Tom decides to take his own life.

This version that Marge created for herself kind of exempts her, in her mind, from the “guilt” she could have had for not having made Dickie love her the same way she loved him. He had other conflicts that she could never help. She leaves Italy and becomes the writer she always set out to be, dedicating her book to Dickie and moving on with her life.

The inspiration for Marge Sherwood in the life of Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith was a popular and somewhat controversial writer and Ripley was her most famous and beloved character. Although Marge has literary dreams, she does not have the author’s sympathy and some biographers suggest that she was Highsmith’s personal outlet because she had a same-sex relationship with a married woman and began creating Tom Ripley while on a trip with her mother. lover for Italy. Marge would have “inherited” much of the criticism that Patricia Highsmith had of her rival. He was preventing them from having a happy life.

If that’s what it is, and it has everything to be, it’s even sadder that Marge was something of misogyny. In chess with Ripley, she starts the game with all the advantages, which hallucinates him. Anyone who has even the slightest knowledge of Sigmund Freud’s thesis knows how much it brought out the worst in the sociopath, indirectly. On the other hand, what woman hasn’t once competed with her best friend for her boyfriend’s time and trust? Toxic men say that women use sex to gain control, and women hate male influence that keeps them away from the conversation.

The machismo against Marge is undeniable: for Tom Ripley everything about her is fake and irritating, while the same characteristics in Dickie are charming and inspiring. Marge is not a saint, she also uses malice when she insinuates that Tom is gay because she thought it would drive him away from Dickie.

Either way, she is the loser of the story. Ripley makes all men see her in a negative light, and sadistically destroys her self-esteem, her memories with Dickie, and her relationship with her boyfriend, who he literally killed. Nobody likes Marge, but she should empathize with all of us. A woman who represents many of us.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.