It is quite daring that even if a classic like Rosemary’s Baby had given way to both a sequel and a prequel, someone would try. The adaptation of Ira Levin‘s book is still one of Roman Polanski‘s best films and one of the great classics of the psychological horror genre. In Apartment 7A, the film directed by Natalie Erika James, we find the answers to some of the mysteries that the 1968 film did not solve and we leave some more to solve.

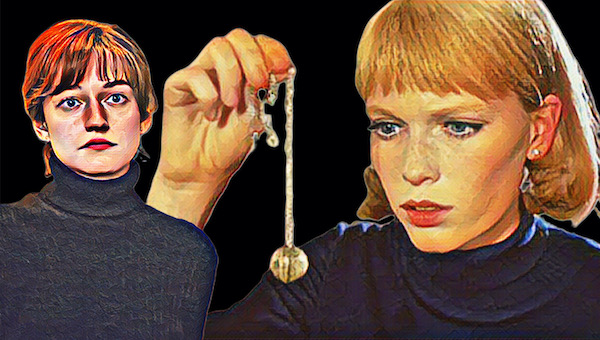

The script’s proposal is to discover the story of Terry Gionoffrio (Julia Garner), the neighbor that Rosemary (Mia Farrow) met in the building’s laundry room and who SPOILER, inexplicably jumped to her death on a cold New York night. Clearly, she was the person the Satanic sect had chosen to be the mother of the anti-Christ, but she decided to break the deal with them.

In the original film, Terry says she was taken off the streets by Rosemary’s eccentric neighbors, hinting at drug addiction and prostitution. Here, Terry is a ballerina who dreams of success on Broadway, but after suffering a devastating injury, she starts using pain medication and has no dreams for the future.

Terry is taken in by an older, wealthy couple (Dianne Wiest and Kevin McNally) who take her to the luxurious Bramford (in reality, the Dakota). As she ascends, mysterious things begin to happen until the tragic culmination of the story. And this cannot be a spoiler, after all, it is a story that begins with us fully knowing the ending.

Julia Garner, as expected, does what she can in a film that makes some ‘curious’ creative choices to get away from the obvious. There are the expected ‘scares’ from a horror film, which is a shame because the brilliance of Rosemary’s Baby lies precisely in the insinuations and suggestions, which is why it is still one of the scariest films ever made, but there are musical scenes that border on the bizarre. It doesn’t add to the narrative; it was a choice that actually hindered the proposal. But let’s move on.

The implicit theme of the entire work – from the female perspective – is the issue of rape, followed by the lack of agency over one’s own body, used for a greater evil. But in the original Rosemary is even more of a victim than Terry, because she is not part of the pact and is used by Guy, her husband, here Terry is manipulated into going along with the plan even though she doesn’t know what is happening. At least at first.

None of this changes the conclusion, but it brings a drama similar to Rosemary’s because the sex was not consensual, there was violence, and Terry – without understanding exactly what happened – begins to suffer gaslighting when she realizes that something is going on behind the scenes.

Apartment 7A manages to weave together the scenes of interaction between the two women, which are brief, in a way that lets fans of the original know that the story has been maintained, but because they chose to insert unnecessary “scares”, the laundry scene was out of place, although it was ok.

The ambitions of Terry, a shy dancer who came from Nebraska to New York and dreams of fame, are sadder than Polanski’s film suggested, especially because she falls for the sweetness of Roman and Minnie Castevet (McNally and Wiest).

The two, by the way, are great and had an even greater challenge because they needed to be consistent with the 1968 film. Particularly Dianne, who already has two Oscars for Best Supporting Actress and is under the shadow of Ruth Gordon’s award-winning performance as the scary and nosy Minnie Castevet. Dianne kept the accent and mannerisms that Ruth gave to the character, but added an even more threatening tone that works very well in Apartment 7A.

The fact that the script wants to be respectful paradoxically makes the film lukewarm. There is tension, a certain anguish too, but it is 100% predictable. The religious paranoia that marked both the book and the film resonated with what in the 1960s seemed like a threat, but in current times it is exactly as Apartment 7A exposes: a theatrical fantasy, without any real weight that makes us truly fear.

Rosemary’s Baby is terrifying because it subverts the social references of “safety” – the elderly couple, the doctor, religion – whose true intentions are more sinister than the character can grasp at first. Not here, Terry quickly realizes that there is always someone wanting something behind a charitable gesture, even if she accepts them also wanting something in return. Her innocence doesn’t work so well, leaving us to follow the story whose ending is known in advance.

That said, the final scene with the introduction of the theme song from the 1968 film gives this prequel even more power. It’s not a classic, but it brings an even darker and sadder perspective to Rosemary. It could be better.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.