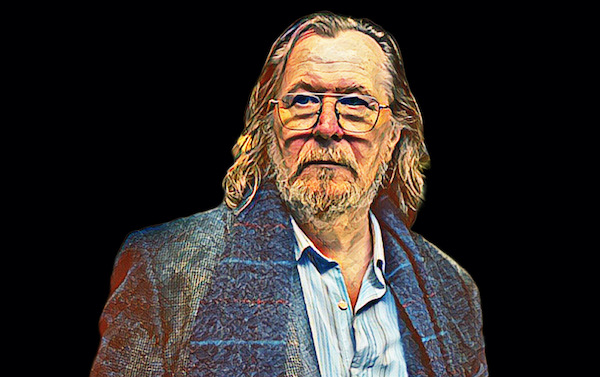

I know I’m being controversial, but the general embarrassment regarding the series Disclaimer, by Alfonso Cuarón, a pure tackiness that only Cate Blanchett justifies watching, is only surpassed by Before, the platform’s new pretentious series, which honestly was already a joke for having Billy Crystal as the protagonist of a horror/suspense story. And it turned out to be a horror, without suspense. Or with forced suspense.

The real problem with Before, as with Disclaimer, is the thread of the story that needs to be stretched to six hours when 80 minutes would be more than enough. That’s why the old discussion of formats and platforms (figuratively speaking, to discuss whether it was something for Cinema or TV) has ALWAYS been relevant. The new form of consumption, streaming, seems to want to boast about having eliminated ‘binarity’ from the equation only to realize that, in this case, it failed.

I will harp on about “time”, an issue that can be both philosophical and mathematical, and here it is both.

What we have today is a volume of content that does not work as a series, but neither does it work as a film. The real impact was to transform TV into an expensive investment like cinema, reducing the hours (there were 26 episodes of 1 hour or 30 minutes, they went to 13, then 8, and now the average is 6), but still having a gap.

That’s right, let’s see how ironic. Until recently, the border between TV and Cinema was in the production process. On TV, with more hours to be recorded in a shorter space of time, there was no room for anything very beautiful (creative, yes!): the cuts and turns had to be faster, with no time for beautiful photography or artistic complexities. Each season was produced annually, in an exhausting process for the cast and crew. Hence, in part, the great appeal of being a movie star is something better than being a TV star.

Until the mid-2000s, it was not absurd to know that we would only have to wait a few months to continue with our favorite series. That has changed. Now how does it work? It is no longer strange to have to wait two or three years to continue with the plot. This is bizarre because, for example, the story of Stranger Things, on Netflix, in theory, takes place with 13-year-old children, but the child cast is already in their 25s, without having reached a conclusion. In my book, this is a defeat.

That said, let’s get back to the ‘format’. Due to the practical issue that the day only has 24 hours and the linear TV schedule is restricted to this, there is a mandatory mathematical calculation to fit the product into the programming schedule. In cinemas, films are also scheduled considering the 24 hours, but, in general, starting in the early afternoon and inserting the last session before midnight. To have a larger audience and supply, worldwide experience has established that a film should have a minimum duration of 1h10 (70 minutes), with the ideal average for TV being between 1h20 (80 minutes) and 1h30 (90 minutes). Long titles would reach close to two hours (120 minutes) and only exceptions would exceed this limit, such as Titanic (3h15 totaling 195 minutes) or the Lord of the Rings trilogy, where each film (in the cinema) had an average duration of 3h (180 minutes).

Discussing length has never been an easy topic. Nowadays, directors like Christopher Nolan and Martin Scorsese only deliver works that are over 3 hours long, a topic I have already discussed here in Miscelana. I have also discussed the challenge of transforming books into films or series, with different results and challenges.

Let’s look at the length of The Lord of the Rings (the films), which encompasses this topic. Adapting the books of over 400 pages with a universe rich in settings, battles, and magical beings in just over 3 hours can be considered short. Many believe that the series format – with multiple seasons and episodes – would be ideal. This is indeed a subjective discussion, after all, this was precisely the winning argument for Game of Thrones to end up on HBO and not in theaters.

George R. R. Martin wanted a film, but summarizing something that was not even completed in eight seasons was virtually impossible. On TV, with millions invested, it was another matter. Still, there is a group (I’m in) that questions whether House of the Dragon can sustain four seasons without having a belly. In two seasons it is already showing signs of wear and tear. See how the equation seems to be mathematical, but it isn’t?

It seems bizarre to be talking about numbers and doing math when we’re talking about Art, but my experience as a programmer made me realize where the impasse in the market has always been. Overcoming it is not impossible, it is just rare.

So as not to just complain, let’s look at Apple’s great success with Slow Horses. The series, which is a great adaptation of bestsellers and has a great cast, is already in its fourth season with two more confirmed. There are 18 books and when they are filmed, two seasons are produced at a time. This way, we have one season on the air per year and the guarantee of continuity.

Still at Apple, and it’s a coincidence (or not?), Ted Lasso is another positive example. The series is simple and became a craze during the pandemic, but, even in the face of pressure from fans and executives, the showrunner and star of the series, Jason Sudeikis, never changed his commitment: to wrap up the story in four seasons.

That said, the story “ended” in the third, but we were hooked and wanted (and want) more. Is it necessary? Is there anything to tell? The discussion continues and Ted Lasso may soon be produced again. I have doubts about whether it will work.

The mathematical freedom of streaming, which is not limited to the 24-hour schedule of linear TV, was potentially a sea of possibilities, but then comes the question of return on investment, measured in ways that are still incoherent, secret, and confusing. In linear TV, this thermometer is easy: if people watch it when it is on air, it is a success. What is the volume of streaming that can define this concept?

The one who pays the bill, literally and emotionally, is the consumer. The pandemic made us think that we would have a lot of new things every week, then every month, and now, if we are lucky every semester. Yes, the two strikes that stopped work in 2023, those that seemed irrelevant and distant, ended 2024, where we have the constant feeling that something is missing. Of course, by 2025 the reality will be different (at least in the cinema), but the more frequent ‘mistakes’ on all platforms worry me that we are reverting streaming to something new and bad.

Of course, having bad content is inevitable, sometimes executives make mistakes, the public’s taste changes, etc. But if the math isn’t adding up, it’s precisely because the trap is in the gray area of format decision-making. Not every story can sustain a film and not every book can be summarized in a few hours. Knowing which is best requires a large team of professionals.

Therefore, what we are witnessing, and even being guinea pigs for, is a new movement in the entertainment market, and a stage that is no longer just technological. The binary currents of TV (represented by streaming) or Cinema continue to be in heated discussions that mention “experience”, “comfort”, “cost”, and “vision” in the universe of profits and billions of dollars. At the heart of all this is the famous “storytelling”.

We love a good story and we are always telling or discovering one. News is stories told and highlighted by journalists. Songs by musicians. Books by writers. Podcasts by professionals or laymen. Tiktoks, Stories, etc. Our lives are so fictionalized that today the concept of “controlling the narrative” applies to anyone and everyone. Would you know how to determine if you were to tell your life story, whether it would be a book, a series, a documentary, a film, a song, a musical, a painting, a photo, a symphony, or an opera? Everything? Nothing? It would be so obvious to have this premise clear, don’t you think?

Therefore, although, understandably, platforms are making mistakes when trying to redefine models and formulas, the challenge is that common sense, although still an irreplaceable thermometer, is subjective. The fact is that it is possible to perceive whether a story is rich enough to engage us, and, from there, whether it effectively holds us for the time it deserves. Above that, it is torture. Don’t you think?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.