I have to admit that, although I don’t like Netflix’s “updates” of classic works or biographies, it is extremely relevant that the platform brings this content to new generations who, otherwise, would have limited access to timeless and important content. Among them, scheduled to premiere on March 5, 2025, is The Leopard.

The Italian period production revisits one of the most emblematic works of Italian literature, written by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa and published posthumously in 1958, two years after the author’s death. The Leopard (Il Gattopardo), a book, is considered one of the greatest Italian novels of the 20th century and had a great impact not only in Italy but throughout the world, being translated into several languages. The 1963 film, directed by Lucchino Visconti, is one of the most important and acclaimed in world cinema, which means it is extremely bold of the platform to bet on its remake.

Considering that both works are less known to the general public, revisiting them before the series arrives is worth revisiting.

Historical and Cultural Context for the Book

The Leopard is set in 19th-century Sicily, during the period of transition from a feudal society to a new political and social order, marked by the unification of Italy under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi (who would later come to Brazil) and the abolition of the old aristocratic structures. This historical context is told from the perspective of a noble Sicilian family, the Salinas, whose patriarch is Prince Fabrizio Salina, an aristocrat who witnesses and, in a way, symbolizes the end of a traditional world and the rise of a new bourgeois class. Through it, the author explores class, power, decadence, and the inevitability of social and political change.

In this way, the plot is led by the prince who follows the rise of the Italian unification movement, led by Giuseppe Garibaldi (a real figure). Fabrizio is melancholic and reflective, deeply aware of his class’s decadence and the difficulties that this transition of power imposes on the aristocrats. He observes with resignation the rise of the bourgeoisie and the new political dynasties that will take the place of the old nobility.

In contrast, representing the new generation of aristocrats, there is also his nephew Tancredi, who is a charismatic figure who accepts change to maintain his position in society. Tancredi aligns himself with Garibaldi and the forces of unification, seeking to survive and maintain his position through acceptance of the new system, while Prince Fabrizio observes with detachment and resignation. To top it all off, the young man falls in love with Angelica, the beautiful – and rich – young woman, and their romance also reflects the relationship between generations and the complex interactions between them.

The title of the book, The Leopard, is a reference to the figure of the leopard, which is at once imposing and threatened, just like the Sicilian nobility. The leopard is also the symbol of the Salina family, which is in decline. Lampedusa, following the profile of his main character, takes the reader on a deeply reflective and introspective journey, richly described in detail. This makes the book universal and still relevant today.

Yes, relevant today! After all, the metaphor of the decline of the traditional monarchy and the advancement of new political and economic systems can be reflected in conflicts between pre-digital and digital generations, for example. The book questions how social institutions are shaped and shaped by time. It also addresses the limits of aristocratic power in the face of the forces of modernity and capitalism, which parallels contemporary issues of social inequality, class mobility, and political transitions that many countries are still facing.

What critics point out as a major difference is that instead of focusing on the rise of a class or heroic struggle, The Leopard is a study of decadence and disillusionment, where the reality, hopes, and idealism of a generation are undone by relentless and inevitable historical factors. The tone of resignation and fatalism, often associated with existentialist literature, provides a darker and more introspective reading, questioning the nature of social transformation and the position of the individual in the face of history.

The Film Adaptation by Visconti

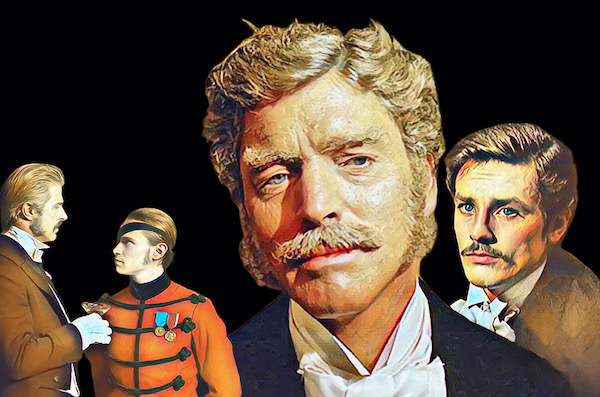

Still at the height of the book’s success in Italy (and worldwide), director Luchino Visconti decided to adapt it for the cinema. Released in 1963, The Leopard is considered one of the masterpieces of Italian cinema and one of the greatest literary adaptations ever made. Visconti, one of Italy’s most influential filmmakers, managed to translate the complexity and depth of Lampedusa’s novel to the big screen while maintaining the emotional density and social critique of the book, with a cast led by Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon, and Claudia Cardinale.

One of the challenges of the film, which the Netflix series will have as an advantage, was to reduce the 20 years of history into less than 3 hours, which required changes from the book, even while remaining faithful to the spirit and essence of the central issues: the transition between generations, the decline of the nobility and the inevitability of social and political change.

The Leopard is known for its stunning aesthetic vision, lavish production, and historical accuracy. Visconti, who had a deep connection to the Italian aristocracy and a critical eye for political transformations, brought an aura of historical realism to the film while remaining faithful to the details of life in 19th-century Sicily.

Visconti also uses the film as a critique of the hypocrisy of the nobility and their failure to adapt to a changing world, reflecting how the ruling classes throughout history tend to protect their privileges while adapting to the new order, often in a covert manner.

Although he was unhappy with the studio’s decision to give the lead role to an American, Visconti and Burt Lancaster eventually came to an understanding, and the actor’s performance as Fabrizio Salina is marked by a melancholy and quiet wisdom that captures the essence of the book’s character—a man who accepts the downfall of his class with a sad and dignified resignation. Meanwhile, Alain Delon, at the height of his beauty, youth, and energy, is as perfect as Tancredi, and Claudia Cardinale, also at her peak, is as charming as Angelica.

Another great highlight, of course, is the soundtrack by the brilliant Nino Rota, melancholic and sophisticated, reflecting the tone of the story and the decadence that permeates the novel. The Italian composer’s music amplifies the sense of loss and inevitability that the novel and the film convey.

The Leopard is considered a masterpiece and received the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1963, consolidating Visconti as one of the greatest filmmakers of his generation and influencing period productions and literary adaptations for the cinema.

The Ball

Like many classics such as the horse race in Anna Karenina or the banquet in Madame Bovary, the ball in The Leopard is a metaphorical moment of great relevance in both the book and the film, not only for its visual grandeur but also for its symbolic and emotional depth. It unites all the central themes of the story: the transition between old and new generations, the decline of the nobility, and the rise of the bourgeoisie. In the film, with impressive choreography, sumptuous costumes, and exquisite art direction, the scene encapsulates the tension between the old and the new, in addition to conveying the melancholy and fatalism of the characters. With music by Nino Rota, of course!

The ball takes place in the palace of Prince Fabrizio Salina (Burt Lancaster), where the Sicilian aristocracy, with its codes and pomp, still tries to maintain control and the appearance of power, even in the face of the rise of the new bourgeois class represented by figures such as Tancredi (Alain Delon) and his bride, Angelica (Claudia Cardinale).

Before the entrance to the ballroom, the scene is prepared with great attention to detail. The palace is adorned with tapestries, chandeliers, and luxurious furniture. Visconti’s camera moves smoothly, capturing the luxury of the decoration and the formality of the interactions between the guests. The attire of the women, with their haute couture gowns and elaborate hairstyles, is worthy of a high society ball, while the men, with their formal attire and serious expressions, carry a certain stiffness, reflecting the rigid conventions of the time.

When the scene finally reaches the ballroom, the camera begins to pan across the large room, showing a multitude of nobles dancing and intertwining in formal dances. The ballroom, lavishly decorated and lit by golden chandeliers, is a visual spectacle of luxury and pomp, reflecting the power and importance of the Sicilian nobility before the unification of Italy. Traditional and vibrant music begins to play as the camera follows the movements of the dances. The rhythms of the classical music, which accompany the dancing couples, reinforce the idea of a decadent aristocracy, still immersed in its pomp and social circus, but already aware that the golden age is coming to an end.

At one point, Angelica, in her exuberant dress, enters the ballroom and is quickly noticed. Her presence is striking not only because of her physical beauty but also because she represents the rise of the new bourgeois class, the class that stands in opposition to the aristocratic world. The music, as it becomes more vibrant and almost hypnotic, underscores the tension between the old and the new, between the generations. The camera focuses on Tancredi, who watches Angelica with desire and a certain enchantment. Tancredi’s gaze, with its more youthful and modern attitude, is contrasted with that of Prince Salina, who sees, with a mixture of pain and resignation, the young woman as the embodiment of inevitable change. The prince, like the old order he represents, feels that he is being replaced, but can do nothing to stop it.

The dance between Angelica and Tancredi symbolizes not only the personal attraction between the two but also the alliance between the old and the new class. Tancredi, although still part of the aristocracy, begins to align himself with the new power that Angelica represents. During the dance, the camera follows them closely, and their facial expressions become more intense, reflecting the complex relationship between the two worlds. Prince Salina, watching from a distance, sees the future approaching, although, as a melancholic character, he is not directly involved. The dance itself is formal and elegant, with precise steps and choreography that reinforce the idea of a world that moves within a set of immutable norms and rules. However, this formality is gradually being replaced by the fluidity and energy of Tancredi and Angelica’s youth, which symbolizes a new future.

Prince Salina watches the ball with an expression of detachment and melancholy. In contrast to the other characters, he seems out of place, as if he were in another temporal dimension, fully aware that the aristocracy to which he belongs is dying. This scene reveals the soul of the character, who feels worn down by time and the inevitability of the changes happening around him. Lancaster’s gaze is deeply charged with sadness and resignation, making it one of the most touching and complex points of the scene. Visconti uses the camera to capture this feeling of loss and of looking back on the past. The camera is slow and reverent, as if he wants to preserve this moment of luxury and formality, although he knows that it is destined to disappear. The contrast between the prince and the other characters is palpable, and his distant position, at the edge of the ballroom, is a visual metaphor for his disconnection from the changing world.

The ball, therefore, is more than just a social sequence; it functions as a representation of Sicilian society in a moment of transition. The dances, music, and costumes present a façade of grandeur and dignity, but there is an undertone of decadence. Prince Salina, aware of the end of his class and the arrival of new power, realizes that the future is beyond his reach. Angelica’s entrance and her dance with Tancredi are the culmination of this process of transformation.

The aura of loss and melancholy of the scene are amplified by Visconti’s direction and Giuseppe Rotunno’s cinematography. The attention to detail, the soft light bathing the characters’ faces, and the adornments of the setting create a sense of nostalgia and farewell as if the ball were a last attempt by the aristocracy to preserve its identity in a world that is rapidly changing.

The scene is also symbolic in that it captures the passage of time – the decay of old customs and the rebirth of the new order. The music, dances, and dialogue are like a metaphor for time in motion, and the ball is a visual portrait of the impossibility of avoiding change.

The Netflix series

The 2025 version will have six episodes and premiere almost 62 years after Visconti’s film, with a cast of Italian stars, such as Kim Rossi Stuart, Saul Nanni, Deva Cassel, and Benedetta Porcaroli.

The plot follows Don Fabrizio Corbera (Kim Rossi Stuart), the prince of Salina, who leads a life full of beauty and privilege. But when the unification of Italy threatens to dismantle the Sicilian aristocracy, Fabrizio decides to protect his lineage — including arranging a marriage between the rich and beautiful Angelica (Deva Cassel) and his nephew Tancredi (Saul Nanni), at the risk of breaking the heart of Fabrizio’s beloved daughter, Concetta (Benedetta Porcaroli), who loves Tancredi. In Visconti’s film, Concetta’s drama is reduced and the series promises to place greater emphasis on the character’s suffering.

The miniseries follows Fabrizio as a disenchanted observer of the progressive and inescapable decline of the Sicilian aristocracy as the bourgeoisie gains power and influence. The historic Expedition of the Thousand, led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, as well as the decline of the Bourbon government and the tension in Sicily, destined to be annexed by the Kingdom of Sardinia, serve as a backdrop, just as in the book. As does Tancredi’s classic conclusion about the reality of the nobility, which has an impact on the book and the 1963 film: “If we want things to remain as they are, things will have to change,” he tells Fabrizio.

The platform treats the production as an investment in an epic. And certainly, one of the great highlights of the year.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.