For lovers of classical ballet, the “end” of this art form has been discussed for decades, as it is essentially focused on the past. Even creative choreographers do not often focus on full-length, long, or repertory ballets, staging pieces that are over 100 years old year after year. In 2025, two of the most significant ballets of recent decades will turn 60. Is traditional classical dance really outdated?

In 2025, two of the most significant ballets of recent decades will turn 60: Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, which premiered by the Royal Ballet in 1965, and John Cranko’s Onegin, first performed by the Stuttgart Ballet in the same year. Both represent an attempt to renew the tradition, bringing an intense dramatic approach and technical demands that challenge the dancers. The fact that these works remain in the repertoire of companies around the world suggests that classical dance remains alive and relevant.

What is called ‘repertoire ballet’ is, for the most part, narrative ballet, that is, those that tell a story—unlike abstract ballets, such as those by George Balanchine, which prioritize form and musicality without a defined plot. Something he hated, but many call “symphonic ballet”.

The questioning of the contemporaneity of classical ballet comes from the resistance to creating new repertoire works. While major companies continue to reprise Swan Lake, Giselle, and Sleeping Beauty, few choreographers dare to expand this repertoire. Alexei Ratmansky and Christopher Wheeldon are some of the exceptions, but their productions are still a minority compared to the traditional titles.

On the other hand, the language of classical ballet continues to evolve in shorter, more experimental works. Choreographers such as William Forsythe and Crystal Pite explore classical techniques in innovative ways, inserting them into contemporary narratives and aesthetics. This evolution shows that, despite tradition, ballet is not frozen in time.

The 1960s and 1970s are also considered a “last great creative flowering” for classical ballet, with names such as John Cranko, Kenneth MacMillan, Maurice Béjart, George Balanchine, Frederick Ashton, and Yuri Grigorovich leading bold productions that are still referenced today. This period can be considered the last great moment of renewal and creativity for classical ballet, where new forms of expression and more contemporary themes were incorporated into the genre, without losing the essence of dance.

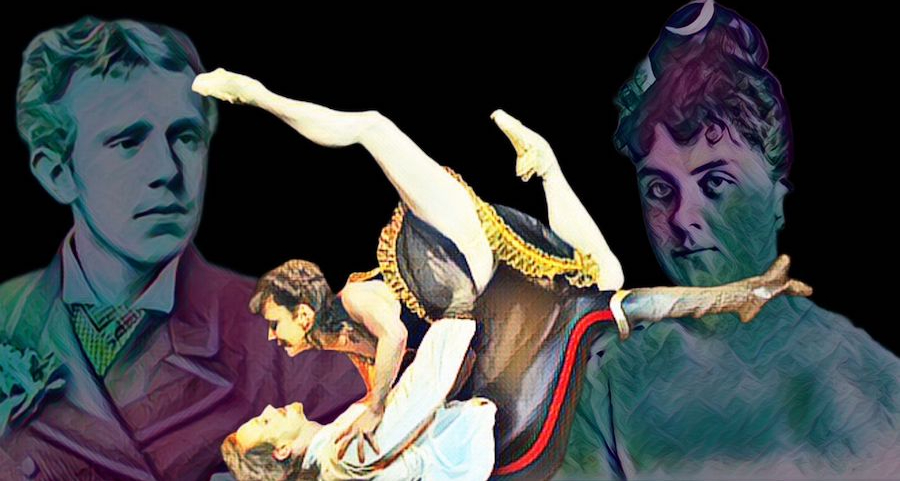

Among the most prominent figures of this era are John Cranko and Kenneth MacMillan, whose ballets stood out not only for the boldness of their choreography but for the emotional depth they brought to the stage. Both, with their versions of Romeo and Juliet, knew how to transform the classic story of tragic love into a visceral spectacle with a more intense dramatic charge than previous versions, elevating narrative ballet to new heights. Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet, created in 1962, is one of the masterpieces of this period, combining sensuality and emotional tension, while MacMillan’s version, from 1965, stands out for the psychological treatment of the characters and a choreographic construction that reinforces the tragedy of the story.

In 1965, Cranko also created Onegin, another fundamental work that is part of this movement to renew classical ballet. Based on Pushkin‘s novel Eugene Onegin, the ballet brought a new approach to the concept of narrative ballet by intensely exploring the psychology of the characters. The work is marked by the emotional strength of its protagonists, especially about unrequited love and regret. Onegin established Cranko as one of the greatest innovators of 20th-century ballet, combining classical technique with a dramatic narrative that still enchants audiences today.

Both choreographers share a common characteristic: the search for a more expressive dance that directly communicates with the audience’s emotions. MacMillan, for example, innovated by integrating classical technique with a modern sensibility, creating works that explored the psychological and dramatic aspects of his characters, an almost revolutionary movement for the time. Cranko, in turn, brought a sensibility that was more focused on the narrative, without giving up refined technique.

Romeo and Juliet and Onegin remain staples in the repertoire of many ballet companies to this day. The Royal Ballet’s current season, for example, celebrates McMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, a signature piece of the company, but also features a production of Onegin, to mark the 60th anniversary of both ballets.

In addition to being personal friends and sharing similar tastes, Cranko and McMillan were deeply inspired by their muses. John Cranko, who left the Royal Ballet for the Stuttgart Ballet, had a detailed vision of narrative and refined technique, and found in Marcia Haydée, one of the greatest Brazilian ballerinas, the perfect interpreter to bring his ballets, such as Romeo and Juliet and Onegin, to life. Her ability to emotionally surrender to the roles was crucial to the depth and impact of these works.

And Onegin, the world premiere took place on April 13, 1965, with Marcia Haydée in the role of Tatiana, Ray Barra as Onegin, Egon Madsen as Lensky, and Ana Cardus as Olga, but it was revised between 1965 and 1967, adjusting the ending to intensify the drama of the final scene between Tatiana and Onegin. The standard version was first performed by the Stuttgart company in October 1967.

Kenneth MacMillan had Lynn Seymour as a key artistic partner and created for her what many consider the definitive version of Romeo and Juliet in 1965. Seymour, with her impressive capacity for emotional expression and impeccable technique, was key to conveying the complex emotions of the ballet, becoming a central figure in the interpretation of her characters, but, as we know, she was overlooked at the premiere.

This is because, even though the legendary balcony pas de deux had been conceived for Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable in 1964, the management of the Royal did not consider that their names would generate interest at the box office. The duo was replaced by Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, who received applause for more than 43 minutes and also starred in the filmed version.

This decision naturally disheartened MacMillan and Seymour, especially since she had decided to terminate a pregnancy for the production and had prepared intensely for the role. The drama temporarily affected her relationship with MacMillan and led to a brief departure from the Royal Ballet for years. Their reconciliation resulted in other notable works, such as Mayerling and Manon, cementing their artistic partnership as one of the most legendary in the history of dance.

During this same period, Frederick Ashton, a great name in British ballet, brought some of his most remarkable works, which also exemplify the renewal of classical dance. A Month in the Country (1960), inspired by Turgenev’s play, is a work that delves into the psychological complexity of its characters, marking one of Ashton’s most sophisticated and dramatic creations. The Two Pigeons (1961), with its tale of romance and separation, combined the lightness of classical ballet with a unique emotional expressiveness, while his revival of La Fille mal gardée (1960, rev. 1963) brought a fresh take to an 18th-century classic, securing a permanent place in the repertoire of British and international companies.

In parallel, figures such as Grigorovich, with his grandiose creations such as Ivan the Terrible (1975) and Spartacus (1956), brought a different approach. By incorporating folk and historical themes, Grigorovich introduced a new dimension to classical ballet, with a strong emphasis on the power of dance to tell epic and emotional stories.

His ballets were grandiose, with impressive sets and costumes, but they also brought to the fore political and cultural issues, connecting ballet to a wider context of struggle and resistance. The fusion of folk elements with classical technique made their works a mixture of ballet and theater, bringing a freshness that resonated with the times and is still revered in many performances.

These creators not only defined a period of great creativity in classical ballet but also paved the way for a new era of innovation and complexity in dance. Whether classical ballet survives only through its great works of the past or whether there is still room for new creations in long form is an open question. However, the continued presence of works such as Romeo and Juliet and Onegin indicates that the emotion and power of classical dance still captivate audiences, and perhaps this is what ensures its longevity.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.