Among the many works that make up the canon of classical ballet, few have the creative, emotional, and symbolic power of Swan Lake. You can ask Artificial Intelligence to translate into numbers how many productions worldwide take place each year, and the answer is: “It is impossible to give an exact number of performances of ‘Swan Lake’ worldwide”.

Without exact numbers to translate the popularity of almost 150 years, it is still worth looking at the magic in a strong story, for its mixture of fairy tale and tragedy. where the princess is transformed into a swan by a wizard who disguises himself as an owl. Given this simplistic summary, it would be difficult to explain why, despite facing criticism and almost failing at its premiere, Swan Lake is still the most popular ballet in history. It holds this position not only because of its frequency on stages around the world, but also because of its cultural impact, its recognizable soundtrack, and the emotional and technical depth required of its performers.

Since its premiere in 1877, in Tsarist Russia, to its countless contemporary revivals, this tale of love, witchcraft, and metamorphosis has remained an enigma that audiences insist on revisiting — and perhaps never fully deciphering. But why does Swan Lake hold such fascination? Why does it continue to be the most performed and recognized ballet in the classical repertoire, crossing centuries, borders, and aesthetics?

The answer lies not only in the beauty of Tchaikovsky‘s score, although this is, in itself, one of the most powerful ever composed for dance. Nor is it limited to the traditional choreography of Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, with its symmetrical sets and almost superhuman technical demands. What truly moves the collective imagination is the symbolic force of what Swan Lake represents: a mirror of human duality, a metaphor for the search for authenticity in a world of appearances, and a poetic portrait of the feminine as a territory of sacrifice and desire.

The Myth of the Swan: Purity, Imprisonment, and Transformation

At the heart of the ballet is Odette, the princess transformed into a swan by a sorcerer, condemned to live between worlds—neither fully human nor fully bird. The image of the swan, a being of melancholic grace, already carries within itself a paradox that resonates with human dilemmas: lightness and weight, freedom and captivity, beauty and fragility. Odette is cloistered purity, impossible love, a body that dances even when wounded by the curse of the other.

Her shadow, Odile — the black swan — represents the opposite face: seduction, illusion, imposture. When Prince Siegfried lets himself be deceived by Odile, believing that she is Odette, the archetypal betrayal is consummated: the choice of appearance over essence. It is in this gesture that Swan Lake ceases to be just a romantic tale and becomes a profoundly modern tragedy. Love is not enough. The gaze fails. And the world, ruled by appearances, is the stage for irreversible condemnations.

Technique, Body, and Rapture

Thanks to Petipa and Ivanov, ballet demands a symbolic feat from the ballerina: to be two bodies in one. Odette and Odile are not just opposite characters — they are emotional, technical, and scenic opposites. Odette demands fluidity, arms that wave like wings, and an internalized musicality. Odile demands precision, strength, magnetism, and absolute mastery of time and space, as in the famous 32 fouettés of the third act.

By demanding this performative split, the role of the white/black swan not only consecrates technically brilliant ballerinas — it transforms them into icons. Great names such as Galina Ulanova, Natalia Makarova, Maya Plisetskaya, Margot Fonteyn, and, more recently, Svetlana Zakharova, Misty Copeland, and Marianela Núñez have been immortalized not only for playing the role but for embodying this internal abyss between the swan-woman and the ghost-woman.

The audience, in turn, lives in the trance of this transformation. Each movement of the ballerina seems to translate an ancestral feeling, one in which the body is still the purest language of the soul. The final catharsis, whether with the death of the protagonists or their symbolic ascension, is both aesthetic and existential: if we cannot love in the real world, at least we can die together in the realm of the imaginary.

Mirrors of Modernity

The persistence of Swan Lake over time is also due to its symbolic malleability. Several modern reinterpretations have explored gender fluidity, the conflict between desire and identity, and the critique of spectacle. Matthew Bourne‘s revival, for example, with male swans in place of traditional ballerinas, subverted the conventions of classical ballet to speak of repression and sexuality in the world of ballet.

Black Swan, a film by Darren Aronofsky, used ballet as a metaphor for psychic fragmentation, the pressure for perfection and the destruction of the self in the face of art. Natalie Portman – who won the Oscar for Best Actress – plays not only Nina, but all the swan women who have ever existed: those who bent themselves to the limits of form, who confused body and sacrifice, who were consumed by the beauty they portrayed.

These contemporary readings do not exhaust Swan Lake – they only reinforce its power. Ballet survives because it speaks of that which cannot be resolved, of that which escapes. What, after all, is more timeless than loving someone and not being able to touch them? Rather than being betrayed by the gaze of another? Or wanting to be free and, at the same time, not knowing where the exit door is?

Echoes of the Past: History and Transformation of a Classic

Although today it is synonymous with excellence and romanticism in ballet, as mentioned, Swan Lake had an unpromising premiere. The first production, in 1877, at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, with choreography by Julius Reisinger, was a failure with both critics and audiences. The production was considered confusing, and not even the music, revered today, was understood in its depth.

It was only after Tchaikovsky died in 1895 that Swan Lake found its canonical form. Under the direction of masters Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, the new choreography, staged at the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, consolidated the four-act structure and established the codes that are still preserved today: the great adagios, the symmetrical pas de deux, the corps de ballet in swan formation — an image that would become an icon of classical dance.

Tchaikovsky’s score was also reworked for this version. With its lyrical yet dramatic orchestration, it alternates between dark and ethereal themes, using leitmotifs to characterize the characters. Odette’s theme, for example, is introduced with harps and strings in minor keys, while Odile is accompanied by more incisive, almost martial passages. The music does not accompany the scene — it suggests it, precedes it, intensifies it. Tchaikovsky did not just write music for dancing: he wrote music for suffering.

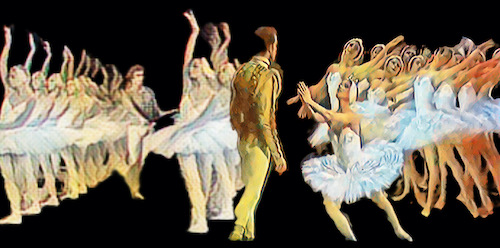

The Corps de Ballet: Symmetry as Drama

Unlike other works in the classical repertoire, where the corps de ballet has a decorative or structural function, in Swan Lake it acquires symbolic prominence. The 24 ballerinas who play the swans are not just a backdrop: they are Odette’s own world. They are her prison and her companion, her nature and her curse.

The geometry of the choreography — lines, mirroring, canons — visually reinforces the theme of the double, repetition and confinement. Each bending arm, each synchronized arabesque, seems to say: “there is no way out”. The swan dance is thus a portrait of the oppressed collective, of disciplined beauty, of regimented sensitivity.

This aesthetic also resonated in later visual languages: from fashion photography to pop music videos, the image of the “army of swans” became an icon of femininity, melancholy, and silent power.

Psychoanalysis and the Inner Lake

It is no surprise that Swan Lake has become a rich source of psychoanalysis and deep symbolic readings. The figure of the double — Odette/Odile — refers to the split of the Self, to the Jungian shadow, to the duplicity between desire and repression. The lake, in turn, can be read as the unconscious: deep, mysterious, governed by laws that escape reason. Odette emerges from this lake as a projection of the feminine ideal: beautiful, tragic, untouchable.

Siegfried, the dreamy prince, seeks in this lake what the real world does not offer him — perhaps even himself. His fall into Odile’s trap is a fall into narcissism, into the illusion of control. He chooses the simulacrum, the distorted image. The final tragedy — death, dissolution in the lake — is also a form of reintegration: the return to the unconscious, to the beginning, to the lost truth.

The Ballerina as Archetype

The ballerina who dances Swan Lake does not just play a role: she becomes an archetype. It is no coincidence that the image of the ballerina in a white tutu, with her arms arched, her head slightly tilted, is one of the most reproduced in Western culture. In a world that transforms the female body into a spectacle, Swan Lake transforms this spectacle into poetry. But a poetry that exacts a high price.

The role of Odette/Odile is physically exhausting. It demands absolute technical mastery, but also a rare emotional surrender. The ballerina is constantly dissolving between the human and the animal, between sweetness and perversion, between gesture and affection. It is no wonder that many ballerinas see this role as the peak and the limit of their careers. It is a journey. Unsurprisingly, for a ballerina to become a ballerina, she needs to have Swan Lake in her repertoire: it is part of the rite of passage.

We Are the Swan

Watch Swan Lake is more than just consuming a work of art: it is seeing yourself reflected in it. The duality between Odette and Odile exists in all of us. The desire for freedom and the fear of loneliness. The search for true love and the surrender to the most dangerous illusions. The longing for lightness in a world that demands weight.

Maybe that’s why, generation after generation, we return to the lake. We know the ending. We know it hurts. But still, we want to see the swan dance. Because there, between the plié and the last gesture before falling, there is something that reminds us that, even captive, we are still beautiful. And that, at least on stage, pain can be transformed into flight.

The Swan Doesn’t Die

If Swan Lake is still performed in theaters all over the world, filling audiences and moving generations, it is because we are not just talking about a ballet: we are talking about an essential fable. A fable that reminds us that beauty is always transitory, that love demands mutual recognition, and that the body is the first battlefield between being and appearance.

More than a visual spectacle, Swan Lake is a ritual — where the audience sees on stage not just a ballerina twirling in a white tutu, but something that pulses in the depths of the human soul. The swan, after all, is not just the character. The swan is each one of us, trying to dance while falling.

In time: the new season of the play at the Theatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro opens in May, bringing the star of the Royal to the stage for the first time: Mayara Magri. We will talk more about this 150-year-old classic until then. And later, of course.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.