Of the many songs that make up the musical theater repertoire, few reach the dramatic and vocal heights of Gethsemane (I Only Want to Say), the centerpiece of the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar. Written by Andrew Lloyd Webber (music) and Tim Rice (lyrics), the song captures the most intimate and heartbreaking moment in Jesus’ life: his solitary agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, when, faced with imminent death, he questions, hesitates, and ultimately accepts.

Originally created as part of a concept album released in 1970, Gethsemane quickly became a landmark musical that would revolutionize the genre. Jesus Christ Superstar, released on stage the following year, proposed a bold reinterpretation of the last days of Christ through the language of rock, bringing the sacred closer to the human, the divine closer to visceral pain.

In the song, Jesus does not appear as an unattainable figure, but as a man filled with doubts, in direct dialogue with God, sometimes pleading, sometimes confronting. “I only want to say / If there is a way / Take this cup away from me”, he sings, in verses that oscillate between prayer and despair. The tension builds until it reaches a cathartic climax, with extreme high notes and a scream that became the work’s signature. Musically, Gethsemane demands remarkable technical mastery, with a vocal range that exceeds G5, precise breathing and, above all, total emotional surrender.

It is no wonder that it is considered one of the most difficult male songs in musical theater. Performing it goes beyond singing — you have to inhabit each word, expose your soul. The background to this difficulty is also present in the story of the creation itself: Webber composed the melody with clear influences from the psychedelic rock of the time, and the first person to give voice to this conflicted Jesus was Ian Gillan, lead singer of the band Deep Purple, on the original album. Gillan never played the role on stage, but his recording remains a fundamental reference for its vocal strength and rawness.

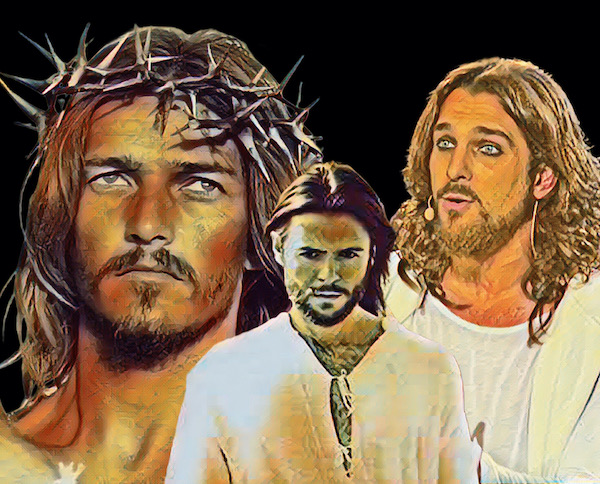

Over the decades, many interpreters have dared to climb this musical mountain. Among the most famous is Ted Neeley, whose performance in the 1973 film is still remembered today for his anthological final scream. Interestingly, Neeley never said goodbye to Jesus: he continued to perform the role on tours and in concerts for decades, even after he was 70 years old. His artistic longevity is impressive — and moving. For many fans, seeing him playing Gethsemane today is witnessing the fusion between character and interpreter, in an almost mystical delivery.

Over the decades, many performers have dared to climb this musical mountain. Among the most famous are Ted Neeley, whose performance in the 1973 film is still remembered for its final, legendary scream; Steve Balsamo, whose performance in London in 1996 is considered by many to be definitive; as well as names such as Ben Forster, Gethin Jones and even Adam Lambert, who in different contexts have brought new light to the piece.

In Brazil, the actor Igor Rickli played Jesus in a national production and courageously faced the vocal and interpretative challenge of the song.

It is common for fans to associate Gethsemane with other renowned names in musical theater, such as Michael Crawford, Michael Ball and Colm Wilkinson, but there are some important distinctions to make. Crawford, immortalized as the first Phantom of the Opera, and Ball, a reference in productions such as Les Misérables, have never officially performed this song.

Colm Wilkinson, with his powerful and striking voice, has sporadic recordings of singing excerpts from Gethsemane in concerts and specials, but has not starred in the role of Jesus in complete productions. His name is often remembered by fans for his performance as Judas in concert versions and, above all, for his legacy as Jean Valjean — another vocal mountain of musical theater.

But the power of Gethsemane does not lie only in its technical complexity. What makes it unforgettable is the way it translates, in sound, the vulnerability of a figure accustomed to perfection. It is a prayer that bleeds. A doubt that echoes. A moment of crisis of faith that, paradoxically, reaffirms sacrifice. Perhaps that is why, even so many years after its creation, it continues to reverberate — on stages, in headphones and in the emotions of those who allow themselves to truly listen to it.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.