We are two months away from the premiere of the third season of The Gilded Age, and it is worth mentioning that one of the new characters, the painter John Singer Sargent, will be played by actor Bobby Steggert. Sargent is one of the names that was not only “inspired” by real figures, but was actually a real name from the golden age. And of course, his appearance on the series will be to portray someone important

John Singer Sargent was the most famous portraitist of his generation — and perhaps the most complete visual chronicler of the so-called Gilded Age, a period of splendor, inequality, and transformation in the United States between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Born in Florence to expatriate American parents, Sargent grew up between European capitals and was educated in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he received impeccable technical training. But his talent went beyond academic boundaries: he developed a loose, vibrant brushstroke that was deeply sensitive to light and movement, capable of capturing both the luxury of clothing and the fleeting emotions of those who wore it.

This balance between formal rigor and expressive freedom made Sargent the ideal painter to portray the elite of the Gilded Age—a class obsessed with prestige, European tradition, and the consecration of their public image. Through portraits, these newly rich sought the aura of nobility that their surnames did not yet carry. Being painted by Sargent, an artist who frequented the salons of Paris, London, and Venice and had friends like Henry James, was more than a status symbol: it was a rite of passage into transatlantic high society.

Sargent traveled frequently to the United States, especially between 1887 and 1917, creating commissioned portraits for families such as the Vanderbilts, Astors, Whitneys, Gardners, and other members of the American elite. His portraits, especially of women, are a lesson in psychological observation. The glitter of the dresses, the velvet, the jewelry, the meticulous lacework, everything is there — but also the evasive glances, the controlled smiles, the slightly off-pose gestures. He recorded the performance of power with a discreet irony, almost imperceptible but undeniably present.

The portrait of Caroline Astor

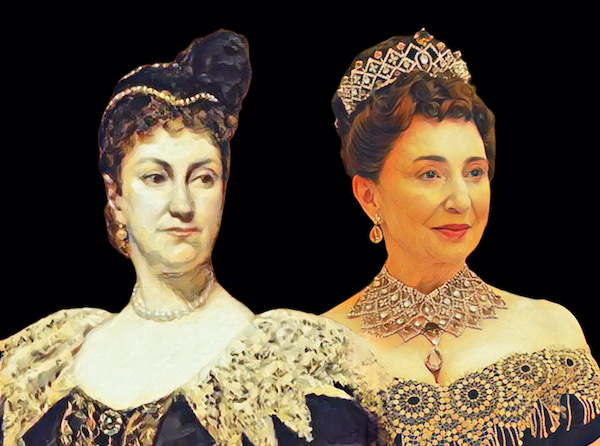

One of the most emblematic portraits of this period is that of Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, painted by Sargent around 1890.

The undisputed matriarch of New York society and the guardian of the select group of the “Four Hundred”, she appears in the portrait wrapped in black, with an air of solemnity and dominance. The composition is austere, but striking: her body occupies the space like a monarchical figure, with a double pearl necklace and embroidered cuffs, next to an imposing vase of flowers. There is something priestly about her—a sort of queen of social morality, both revered and feared.

The choice of black for the dress can be read as a symbol of mourning (for the death of her husband) or of sober authority. But the look on the subject’s face, fixed and firm, conveys a kind of silent defiance: the certainty of her position. Sargent softens the socialite’s features slightly without dehumanizing her, creating an image that mixes reverence and criticism. He seems to say: “Here is power—but look how it holds up.”

This portrait is still considered one of the definitive images of the Gilded Age and is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In the series, Donna Murphy has been a magnificent Mrs. Astor, challenging the newcomer Bertha Russell (Carrie Coon) in everything. Her great defeat in the Opera Wars will have consequences for the fragile “friendship” of the two women, and Sargent will clearly be in the middle of yet another dispute between the two.

Alva Vanderbilt: The Significant Absence

Here’s a detail that might be different in the MAX series. Bertha is inspired by the story of Alva Vanderbilt (later Alva Belmont) — perhaps the most daring and theatrical figure of the Gilded Age, but she was not portrayed by John Singer Sargent. And that absence says a lot.

Alva was married to William K. Vanderbilt and stood out for engineering the Vanderbilts’ meteoric rise to the top of New York society, breaking down barriers that the old guard, led by Mrs. Astor, tried to keep firm. She was a woman of vision, determined, progressive, and most of all, a mastermind of her own narrative. A patron of architects, an outspoken feminist, and a social strategist, Alva preferred to manipulate her image through grandiose events, palatial residences, and carefully choreographed photographs, rather than submit herself to the interpretive gaze of a painter like Sargent.

It is plausible that Alva simply chose not to be painted by him—or that, if there was an attempt, she declined in the face of the control that the artist and demanded over the final result. Sargent was not a painter of easy vanity. His brush saw more than the eye wished to show, and it is possible that Alva, always attentive to the construction of her image, preferred to avoid this type of exposure.

This absence, in itself, is revealing: while many figures of the Gilded Age sought in Sargent the validation of their prestige, Alva built her own stage — and was the main actress of her story. Her rejection of the aesthetics of the painted portrait echoes her rejection of the social conventions that limited the role of women.

Bertha will certainly want to have a Sergeant in her room, don’t you agree? We’ll see how her negotiation will go. After all, John Singer Sargent was more than a painter of the elite — he was its most sophisticated mirror, revealing both the brilliance and the cracks of the Gilded Age. His portraits are visual testaments to a time when appearance meant power, and portraiture, eternity. But figures like Alva Vanderbilt, who refused this immortalization, show us that, sometimes, the silence of an absent portrait speaks even louder than the oil on canvas itself.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

2 comentários Adicione o seu