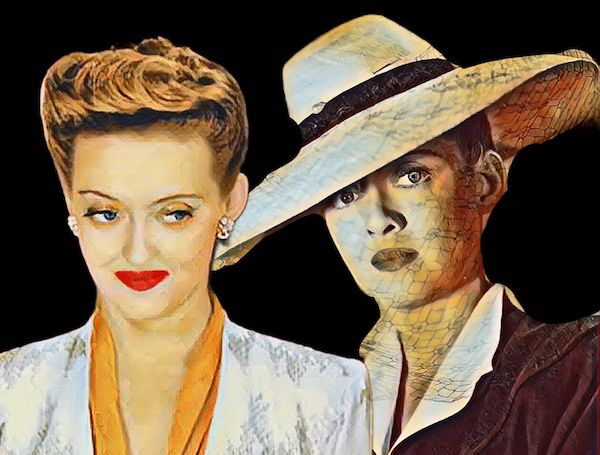

Released in 1942, Now, Voyager is one of the greatest classics of Hollywood cinema from the golden age, starring Bette Davis in one of the most remarkable performances of her career. Directed by Irving Rapper and based on the novel of the same name by Olive Higgins Prouty, the film is more than a romantic melodrama: it is a powerful story of transformation, female self-affirmation, and emotional emancipation, in the middle of the 1940s.

The plot revolves around Charlotte Vale, a repressed, shy, and emotionally fragile woman, who lives under the oppressive rule of her authoritarian mother, the rich and tyrannical matriarch of the Vale family, from Boston. Charlotte suffers from nervous breakdowns and low self-esteem, the result of years of psychological abuse. Her life changes radically when she is taken in by a caring psychiatrist, Dr. Jaquith (Claude Rains), who sends her to a sanatorium and then encourages her to take a life-changing trip through South America.

During this cruise, Charlotte emerges as a new woman — elegant, confident, and charming — and ends up meeting Jerry Durrance (Paul Henreid), a kind, sensitive man, but unfortunately married to a cruel wife. Arriving in Rio de Janeiro, the two live an intense but doomed romance. Charlotte returns to Boston as a renewed woman, but with the awareness that her role in the world may not be just that of a frustrated lover. When she meets Tina, Jerry’s neglected daughter, Charlotte sees the chance to repay the world for the kindness she has received, helping the girl overcome the trauma of rejection, just as she once overcame.

The power of Now, Voyager lies in its revolutionary message for the time: a woman does not need romantic love to find fulfillment, and can be the protagonist of her own life by taking control of her destiny. Charlotte’s final line — “Don’t let’s ask for the moon, we have the stars” — became one of the most famous in cinema, encapsulating mature resignation and contentment with what is possible, rather than unattainable fantasy.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, Now, Voyager is a rich study of the formation of the female “self” under maternal oppression. The figure of Charlotte’s mother — narcissistic, controlling, and emotionally abusive — embodies a Freudian archetype of the “devouring mother,” who impedes her daughter’s autonomy, keeping her in a state of emotional regression and dependence. Charlotte’s depression can be seen as a direct result of an unresolved maternal complex, and her hospitalization symbolically represents a journey of mourning and separation.

With the support of Dr. Jaquith, she begins a process of Jungian individuation: she rediscovers her own identity by leaving behind the role of obedient and invisible daughter to become a woman, a subject, a symbolic mother to Tina, and the master of her own destiny. Her love for Jerry is not experienced as an escape, but as a mirror of her capacity to love — and especially to care. By giving up an “ideal” romance to welcome Tina, Charlotte rewrites her history of trauma, not through repression, but through sublimation and care.

Olive Higgins Prouty’s original novel, published in 1941, was already considered bold for addressing issues of mental health, social repression, and female empowerment with honesty and depth. The author herself had personal experiences with grief and depression — her daughter died young, and she suffered psychological shocks that brought her closer to the world of psychoanalysis. Prouty was also one of the first American writers to openly discuss the need for psychological treatment for upper-class women, something still surrounded by stigma. Interestingly, she also financed the psychiatric treatment of Sylvia Plath, who would later pay homage to her with the character Philomena Guinea in The Bell Jar.

Behind the scenes of the film, Bette Davis played a fundamental role not only as an actress but as a creative force. It was she who demanded that Irving Rapper be hired as director, after working with him previously. Davis was at a crucial moment in her career: already established, but increasingly demanding with the roles she accepted. She read the book and insisted that the script maintain the focus on the character’s psychological development.

For the role of the mother, Gladys Cooper was chosen after much competition — Davis wanted the antagonist to be played with restrained coldness, without exaggerated villainization. The casting of Paul Henreid as Jerry also generated debate: Henreid was relatively new to American cinema, and his European accent was seen as a liability. Still, the chemistry between him and Davis became iconic—the gesture of lighting two cigarettes with a single match was Henreid’s own idea, and became one of the most memorable in the history of cinema.

The impact of the film was immense, both critically and commercially. Nominated for three Oscars (Best Actress for Bette Davis, Best Supporting Actress for Gladys Cooper, and winner for Best Original Score for Max Steiner), Now, Voyager solidified Davis as an icon of strength and emotional complexity. The soundtrack, in fact, is one of the most remembered in the history of cinema, especially the chords that accompany the iconic gesture of the cigarette — a subtle symbol of union and contained desire.

The title, taken from a poem by Walt Whitman, is a call to liberation: “Now, voyager, away, away across dangerous seas…”. It accurately reflects Charlotte’s journey — from domestic confinement to self-discovery, passing through emotional tides and unexpected destinations.

Now, Voyager remains a landmark in women’s cinema, a nuanced character study and an example of how melodrama can transcend clichés and touch on profound issues: self-esteem, autonomy, surrogate motherhood, sacrifice, and resilience. It is a film that speaks to all generations, because at its core it is about the universal journey of becoming who you are, despite the expectations of others — an inner odyssey of healing, courage, and choice.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.