No one forgets Swan Lake without first watching the complete version. Mine was not a live performance but a VHS copy of a 1968 Kirov Ballet film recorded by the Soviet studio Lenfilm. I didn’t even know about it at the time, but it is considered one of the finest cinematic recordings of a classical ballet ever made. Today, I lovingly have my copy on Blu-ray.

Directed by Apollinariy Dudko, the version is signed by Konstantin Sergeyev, director of the Kirov at the time. It preserves the choreographic tradition of the Russian school and brings to the screen the aesthetics and emotion of Tchaikovsky’s work with impressive fidelity.

The film’s star is Yelena Yevteyeva, who plays Odette/Odile, bringing dramatic delicacy to the role, with an emphasis on artistic expressiveness rather than technical displays. She represents a more lyrical and emotional lineage of ballerinas and was a standout on the Soviet stage at the time.

The film had a huge impact both artistically and politically. In the Cold War, it served as a piece of cultural diplomacy for the Soviet Union, showing the world the sophistication of Soviet art. Its photography, scenography, and fidelity to the music and choreography made it a landmark in the cinematic record of ballet. Unsurprisingly, its artistic value was recognized decades later in cinema when it inspired the film Black Swan (2010), whose opening scene is heavily inspired by the atmosphere and images of this version.

A ballet of perfection, propaganda, and permanence

In 1968, the world was at the height of the Cold War, and the Soviet Union’s leadership decided that the virtuosity of Russian classical ballet was one of its most effective propaganda weapons. Thus, many preserved films recorded great dance legends and were recorded by the state-owned studio Lenfilm. More than an artistic record, the idea was to have symbols of Soviet cultural excellence, a showcase of the Russian ballet tradition, and also a sophisticated piece of propaganda. And nothing is more classic than Swan Lake.

The great curiosity lies in the behind-the-scenes drama. Directed by Konstantin Sergeyev, with choreography based on versions by Petipa and Ivanov, and musically conducted by Viktor Fedotov, the film starred a young and unconventional ballerina named Yelena Yevteyeva as Odette/Odile, who was chosen at the last minute to replace the already renowned Natalia Makarova.

Makarova was already a big star, but her replacement reveals how difficult it was to survive under the Soviet regime and ended up contributing to her decision to ‘defect’ to the West, just two years later. At that time, Makarova’s international prominence bothered the Kirov leadership, especially after the great success she had on the London tour. Only three years earlier, Rudolf Nureyev had made his “leap to freedom,” causing great embarrassment to the Kirov Ballet, and the attention the ballerina received outside the USSR led to growing tensions with the Soviet authorities. She was already one of the company’s leading stars and was increasingly inclined to pursue an international career, which was not well received by the Soviet government, which tightly controlled the output of its artists.

Specifically, in 1968, Makarova was barred from filming the ballet for reasons of “management” and “political interests,” and was unceremoniously replaced by Yelena Yevteyeva. What could have been a technical or artistic decision had its roots in a series of political and management decisions at the Kirov Ballet.

After leaving the Kirov, Makarova had a successful international career, alternating between performances with the Royal Ballet in London and several Western companies, including the American Ballet Theatre, alongside Mikhail Baryshnikov, who fled to the West in 1973. (Incidentally, Baryshnikov was Yevteyeva’s most frequent stage partner.) In other words, this change of performers and the politics behind it reflect the tensions and challenges that artists faced in the USSR during the Cold War.

A legend among dancers in a perfect work

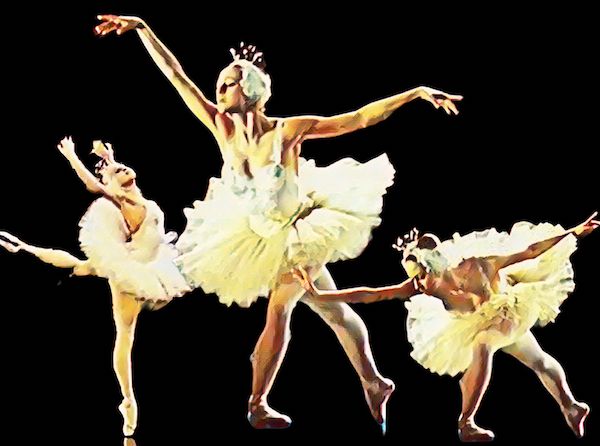

Those outside the dance world may not be familiar with Yelena Yevteyeva, who stunned audiences and critics with an intense, plastic, and deeply sensitive performance in Swan Lake, dancing with John Markovsky as Prince Siegfried and Makhmud Esambayev as Von Rothbart, in a cast that balanced tradition and dramatic daring.

Yelena Yevteyeva was born in Leningrad in 1947 and graduated from the rigorous Vaganova Academy in 1966 under the tutelage of legendary teacher Lydia Tiuntina. Her entry into the Kirov was immediate, and she quickly took on prominent roles. Although she did not follow the typical star path’s classics — her career was not marked by the pursuit of technical prowess or by a rigid adherence to the traditional repertoire — she left a deep mark with dense and theatrical interpretations. In Swan Lake, her film debut, she reveals an ethereal and introspective presence, with absolute control of movement and an unusual emotional delivery. Her Odette was not only the tragic swan, but a soul adrift; her Odile, on the other hand, seductive without caricature, constructed with gestures that suggest more than they show.

The filming of Swan Lake in 1968 is celebrated for several reasons. One of them is its meticulously planned photography: with shots that privilege the fluidity of bodies, smooth camera movements, dramatic lighting, and an almost dreamlike visual palette, the production sought not only to capture ballet as a spectacle but also to translate it into the language of cinema. It is no exaggeration to say that this version raised the standard of ballet filming in the 20th century—something that critics and dance historians acknowledge to this day. The aesthetics of the overture, as already mentioned, served as a direct inspiration for Darren Aronofsky’s film Black Swan (2010), whose first sequence is a retelling of the prologue in which Odette is transformed into a swan by Rothbart.

But the importance of this film is not limited to the artistic field. Soviet cultural propaganda of the 1960s and 1970s planted an idea of refinement, beauty, and superiority in an art as beautiful as ballet. On stage, the great stars of the time included names such as Natalia Makarova, Alla Osipenko, Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov (both now in the West), Vladimir Vasiliev, Maya Plisetskaya, and Ekaterina Maximova, among others, while abroad Margot Fonteyn, Carla Fracci, and Erik Bruhn shone. Among these names, Yevteyeva seemed an exception—less visible outside the USSR, more subtle than Plisetskaya’s theatricality, more introspective than Makarova—but her performance in the 1968 film remains one of the most delicate and haunting ever recorded.

Throughout her career, Yevteyeva excelled in dramatic roles such as Maria in The Fountain of Bakhchisarai, Shirin in The Legend of Love, and Katerina in The Stone Flower, both choreographed by Yuri Grigorovich. Her Giselle, studied for two years under Natalia Dudinskaya’s guidance, is still cited today as one of the most ethereal and devastating ever seen on the Kirov stage. In La Sylphide, Chopiniana, Napoli, and Le Corsaire, her plastic technique—that ability to transform the body into living sculpture—was as impressive as her interpretive intelligence. After retiring from the stage in 1993, she became a rehearsal director and teacher at the Vaganova Academy, where she trained talents such as Svetlana Zakharova, Daria Pavlenko, Veronika Part, and Yulia Makhalina.

To watch the film of Swan Lake (1968) today is to witness not only a golden age of Russian ballet but also a significant chapter in the history of art under authoritarian rule. It is a document that transcends its time: while it crystallizes the Soviet vision of aesthetic perfection, it reveals the tension between control and sensitivity—a paradox that, in a way, defines Yevteyeva’s own career. It is no wonder that this film is considered by many experts to be the most beautiful recording of Swan Lake ever made.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.