Prince Harry often says his greatest fear is that “history will repeat itself,” referring to the tragic fate of his mother, Princess Diana. But, ironically, he has revived an even older trauma of the British monarchy: the love of a prince for an American divorcée who defies royal conventions. If Wallis Simpson had started to fade from public memory, the figure of Meghan Markle brought her back—albeit indirectly—into a new kind of spotlight. The story is inverted: while Edward VIII abdicated the throne for love of Wallis, permanently altering the line of succession, Harry never stood a real chance of becoming king—unless catastrophe befell the royal family. And yet, he provoked a similar wave of shock, institutional rupture, and media warfare. The echoes of that earlier saga span decades and reveal much about what the monarchy accepts, rejects, or fears.

Wallis Simpson was born Bessie Wallis Warfield in 1896, into a traditional Pennsylvania family that had lost its fortune. Orphaned by her father as an infant, she grew up between Baltimore and high society circles she never quite belonged to. She married young, to an alcoholic pilot (suffering domestic abuse as a result), and after divorcing him, wed British executive Ernest Simpson. It was during that second marriage, in 1931, that she met the then-Prince of Wales, Edward. Their affair deepened over the years, even while she was still formally married. When Edward became king in January 1936, a crisis was inevitable.

The new monarch wished to marry Wallis, but the Church of England, of which he was Supreme Governor, would not accept a union with a twice-divorced woman whose former husbands were still alive. Royal advisers and the Prime Minister opposed the match. The solution was abdication. In December of the same year, Edward publicly renounced the throne, claiming he could not fulfill his duties “without the woman I love.” His younger brother, Albert, became George VI—and with that, the young Princess Elizabeth became heir to the throne. Edward’s act of love redrew the course of British history and thrust Wallis into the heart of an unprecedented scandal. In a way, it also reshaped Harry’s own destiny: had Edward remained king, the royal lineage might have looked very different—and Harry, by today’s order of succession, would never have been so near the crown.

She was never forgiven. The royal family ceremonially excluded her, denying her the title of “Her Royal Highness.” The British press—silent during the couple’s courtship—began painting her as manipulative, cold, a classless American without deference or decorum, and the instigator of the greatest constitutional crisis of the 20th century. To the public, she was the woman who lured a king away out of vanity. To the couple’s supporters, she was a victim of misogyny, xenophobia, and institutional resentment.

The couple’s 1937 visit to Hitler intensified suspicions about their political leanings. Documents revealed years later showed the Nazis viewed Edward as a potentially useful ally, should Britain fall. Though there is no proof of direct collaboration, the hints were enough to exile the couple to the Bahamas during World War II, where Edward served as the minimally respected governor. That period, more diplomatic than conspiratorial, was marked by boredom and isolation. Wallis despised the climate, the posting, and the distance from everything she knew. Her letters reflect disdain for the colony and its inhabitants, reinforcing the couple’s negative reputation.

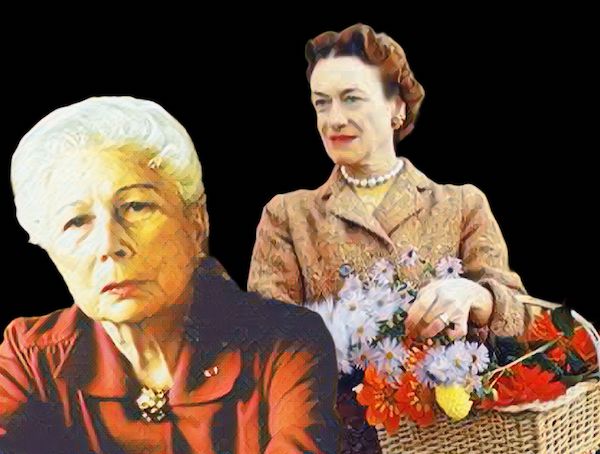

After the war, they settled in Paris, living among parties, art collections, Cecil Beaton portraits, and solitude. They became eccentric social figures—sought-after at dinners and featured in magazine covers—but always as the couple who gave up an empire for love. Edward never overcame the loss of the throne. Wallis lived between privilege and bitterness, adapting to the role of social hostess—a peripheral celebrity, with neither homeland nor real power. Their marriage endured, though marked by silences and poorly concealed longings.

When Edward died in 1972, Wallis sank into long decline. Her final years were sad and reclusive. Suffering from dementia and nearly mute, she came under the care of French lawyer Suzanne Blum, who gradually assumed control over her assets and limited the duchess’s contact with friends and staff. Reports describe negligence, manipulation, and financial exploitation, including the sale of valuable items without clear consent. Blum presented herself as the guardian of Wallis’s legacy, but many biographers view her as a shadowy figure who seized on the duchess’s vulnerability to gain total control over her fortune and public image.

Wallis died in 1986, aged 89, nearly forgotten—the woman who once shook an empire, now reduced to an enigma surrounded by ghosts.

Wallis’s public image has been re-evaluated in recent decades. The series The Crown portrayed her as elegant, melancholic, and ambiguous. The film W.E. (2011), directed by Madonna, aimed to rehabilitate her completely, portraying Wallis as strong and wronged, caught in a web of forces she could never control. As an American, Madonna said she was shocked by the hatred the British still felt toward Wallis and felt compelled to tell her story through a sympathetic lens. However, the film failed both critically and commercially. Accused of superficiality, narrative confusion, and excessive stylization, W.E. lacked the depth to rewrite the dominant narrative and was dismissed as an aesthetic attempt without substance.

Now all eyes are on The Bitter End, an upcoming film centered on the duchess’s final years. Promised as a psychological portrait, it aims to explore her isolation, dependence on Blum, and the physical and symbolic deterioration of a woman the world preferred to demonize rather than understand. There is potential here to reveal a more human Wallis, trapped in a role she never fully chose. The title, ambiguous, alludes both to a literal end and to the bitterness that marked her trajectory. The film is expected to resonate with the present moment, especially following the self-imposed exile of Harry and Meghan.

Comparisons to Meghan Markle are inevitable. Both American, both divorced, both targets of media campaigns and institutional marginalization. Yet key differences remain: Meghan, unlike Wallis, entered the royal family with initial popular support, had a voice, resources, and a prince who had no real power to lose. Wallis, in contrast, was a casualty of a time without social media, without a free press, and of a man who abandoned the throne but never quite renounced the system that had rejected them.

And yet, there is an intriguing nuance: while Meghan Markle has become a polarizing figure and subject of intense scrutiny, Camilla Parker Bowles—once long rejected by the public as the “other woman” in Charles and Diana’s marriage—managed, over time, to transform her image and be accepted as Queen Consort. That contrast sheds light on how the monarchy and the public choose their villains—and more importantly, when they choose to forgive them. Camilla was, for years, seen as a threat to the dynasty’s continuity, yet is now embraced and celebrated. Meghan, who never truly threatened the line of succession, is depicted by segments of the British press with a level of vitriol comparable to that faced by Wallis. What has changed—and what hasn’t—exposes the selective dynamics of inclusion, blame, and redemption that still prop up the royal mythos.

In the end, perhaps Wallis Simpson was neither heroine nor villain, but rather an unsettling mirror for the monarchy: revealing how love can be revolutionary—and how fiercely the institution resists changes that don’t come from within. If history repeats itself, it’s because the ghosts never left. They simply changed their names.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.