The much-anticipated adaptation of the American literary classic, East of Eden, by John Steinbeck (translated in Brazil as Vidas Amargas), is already in post-production and will feature Florence Pugh as the hated and hateful Cathy Ames, in a miniseries written by Zoe Kazan (the granddaughter of the original film’s director, Elia Kazan). The premiere is expected in early 2026, and it clearly aims to sweep awards season.

Although the novel is based on the biblical story of Cain and Abel, it is the cruel and psychopathic Cathy Ames who can be seen as the central character. She is one of the most disturbing female constructs in American literature. A fascinating and enigmatic figure, Cathy escapes easy labels like “villain” or “antagonist” to embody something deeper: the possibility of absolute evil within the human condition.

Steinbeck conceived her as a direct counterpoint to the idea of free will and redemption — a character who seems born incapable of feeling empathy, remorse, or love. The upcoming Netflix adaptation promises to delve into this dark psychology that still provokes discomfort and fascination today. One could also argue that, in a time of widespread true crime consumption and interest in psychopaths, Cathy will finally be “understood.”

Dark origins: the childhood of a sociopath

From early childhood, Cathy displays signs of deviant behavior. Instead of childish innocence, we see coldness, manipulation, and a subtle pleasure in the suffering of others. She learns early on to use her beauty as a tool of domination and, while still a teenager, arranges her own parents’ deaths by setting their house on fire. The crime is disguised as an accident — an early demonstration of her ability to manipulate appearances and evade consequences. She doesn’t act out of trauma or self-preservation, but out of calculation: Cathy eliminates obstacles as if crossing off items on a list.

This absence of moral conscience is more than cruelty; it is a structural void, an emotional black hole. Cathy feels no guilt, and her actions stem not from impulsiveness but from a perverse inner logic in which control over others is the only source of pleasure. Steinbeck seems to suggest that she was born this way, beyond redemption.

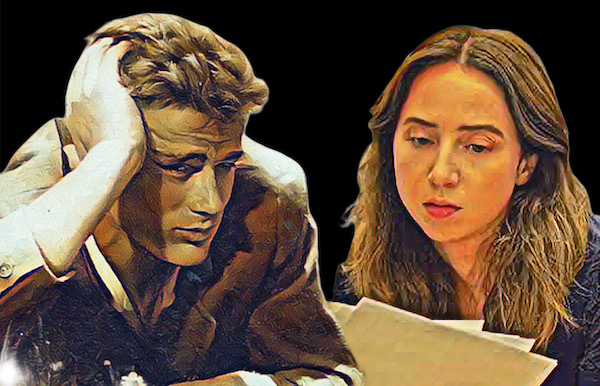

In Kazan’s film, starring James Dean, this primal part of the story was removed to keep the film under two hours. Also, the goal was to spotlight Dean as the protagonist, which is why the script never clearly explains why Cathy’s mother is absent from her children’s lives, vaguely suggesting it’s because she’s a prostitute. A simplistic and unfair version, even for a character as controversial as Cathy Ames.

Entering the Trasks’ lives: manipulation and destruction

After years of drifting and exploiting men for personal gain, Cathy (Pugh) is brutally beaten by a pimp and left for dead. In a near-biblical scene of deliverance, she is found by Adam Trask (Christopher Abbott) and his brother Charles (Mike Faist). Adam, enchanted by her fragile beauty and victim aura, takes her into his home. Despite Charles’ reservations — he senses something dark in Cathy — Adam falls in love with her blindly and devotedly.

Cathy, for her part, sees in Adam a convenient escape route, an easily manipulated man. She marries him but never shares any real emotion. When Adam decides to take her to California and build an ideal family life, Cathy is already planning her next move. After giving birth to twins — Cal and Aron — she shoots Adam and abandons him, leaving the children behind. The gesture sums up her nature: cold, strategic, and incapable of any emotional bond, not even with her own children.

Kate: reinvention and total control

Under the new name Kate, Cathy assumes a role she masters completely: that of a brothel madam. There, she not only works as a prostitute but also quickly manipulates and poisons the previous owner, Faye, until she inherits the business. In the sexual underworld of Salinas, Cathy wields absolute power, controlling clients, employees, and rivals through a mix of blackmail, poison, and icy charm.

The brothel is the perfect metaphor for her worldview: human relationships reduced to transactions, bodies as commodities, emotions as weakness. It is a space where her nature can flourish without the constraints of morality. And yet, even in her total dominion, Cathy/Kate finds no peace. Her existence is marked by isolation and an incapacity for genuine pleasure. She doesn’t love, doesn’t attach, doesn’t dream. She survives, dominates, and destroys — but never truly lives.

The downfall: aging, paranoia, and suicide

Over time, Cathy’s physical and mental health began to deteriorate. The control she so cherished slips through her fingers. The past returns in the form of children who grew up without her, especially Cal (Joseph Zada), who inherits her darkness, but with moral nuances she never had. The figure of the Chinese servant, Lee, absent from Elia Kazan’s version but crucial in the novel, offers constant moral reflection, countering Cathy’s nihilism.

Old age and the loss of power become unbearable to her. Realizing her beauty is fading, her manipulations are no longer effective, and her children reject her maternal identity, Cathy chooses suicide. She leaves behind a note and a sum of money, as if attempting — for the first and only time — a human gesture. But it is too late. Her life was an emotional desert where no affection ever took root.

Motivations and archetypes: is evil essence or choice?

Steinbeck portrays Cathy not as someone corrupted by the world, but as a kind of moral anomaly. She is an allegory of irredeemable evil, a female Lucifer — beautiful, seductive, and fatal. But at the same time, her existence raises an unsettling question: was she born this way, or did she become this way? The answer is never explicit. The lack of clear causes (abuse, trauma, poverty) is precisely what is most frightening.

She represents a form of evil that doesn’t need justification — it simply exists. Her opposition to Adam — the idealist striving to build a familial Eden — forms the narrative’s core. As in the biblical story of Cain and Abel, which serves as the novel’s backdrop, Cathy may embody the unrepentant Cain — the one who kills and moves on. She is the “east of Eden” — exile, moral banishment, the soul’s no-man’s land, the opposite of redemption. While characters like Adam or Cal struggle to overcome their flaws, Cathy sees no value in that. For her, the world is a game of power — and she intends to win, even when all is already lost.

But since East of Eden is a modern reinterpretation of the Cain and Abel myth, the author’s intent was to portray Cathy as the serpent — the external agent that corrupts, tests, and poisons. She abandons her children to their fate, and this gesture echoes in the conflict between the brothers Cal and Aron (Joe Anders). By denying love, Cathy spreads the venom of rejection across generations.

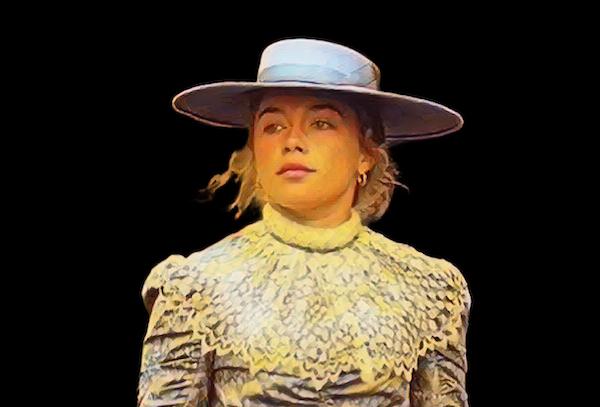

Florence Pugh as Cathy: a perfect choice?

Florence Pugh, with her ability to oscillate between vulnerability and brutality (as seen in Midsommar and The Wonder), seems made for the role. Cathy demands a kind of unfiltered performance: there is no room for empathy, only for the abyssal allure. Pugh’s portrayal is expected to explore the character’s magnetism, her ability to bend others with a smile, but also the inner void growing within her like a weed.

In the new adaptation, there is potential to fully develop Cathy’s arc — from murderous girl to brothel empire, from escape to final collapse. What the 1955 film merely hinted at, the Netflix series can lay bare: the raw, unflinching portrait of a woman who never wanted redemption.

The darkest shadow of Eden

Cathy Ames is one of literature’s most disturbing characters, precisely because her evil has no clear cause, and perhaps doesn’t need one. In East of Eden, she represents the most unsettling aspect of humanity: the absence of love, the refusal of communion, the pleasure in destruction. Her trajectory is a voluntary descent into hell, without cries for help. I’d argue she emerged ahead of her time, when personality studies were still in their infancy and mapping sociopathy was virtually unknown. It’s easier to draw her as demonic.

That’s why I wonder if the Netflix version will try to reinterpret Cathy Ames through today’s lens. Her psychopathy is undeniable, but there could be a perspective of a pragmatic woman using the weapons she had to survive and control her own fate. The scene in which Adam visits her years later and still projects the image of the ideal wife onto her, prompting laughter from Cathy, suggests that she could also be seen as the shattered mirror of the romantic ideal. And no one likes to see their reflection distorted. We’ll see whether Zoe dares to attempt an “updated” redemption of the villainess…

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.