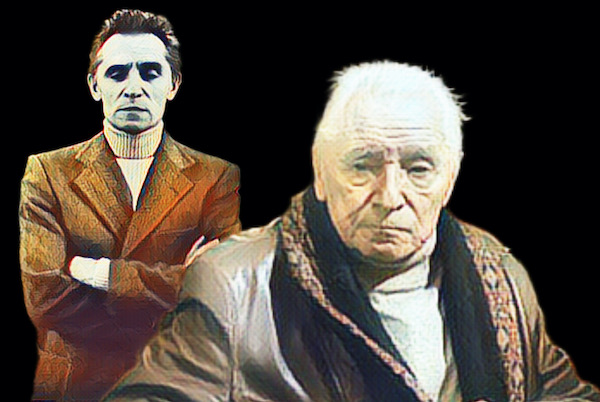

Hours late, but with a saddened ballerina’s heart, I mark the passing of Yuri Grigorovich, at 98, in Moscow. The former dancer, choreographer, and director of the Bolshoi Ballet for 31 years—covering its most historically prominent period—was known for his genius as well as his intransigence and firm hand, a figure as archetypal as ballet films often portray.

Of short stature—he was 1.52m tall—he created gigantic and brilliant ballets: Spartacus is his signature piece (though I prefer Ivan the Terrible), and he was regarded as a tyrannical, arrogant, but indeed brilliant leader. Grigorovich was also seen as the architect of the Bolshoi Ballet’s golden age and one of the most influential—and controversial—figures in 20th-century ballet. His choreography was aesthetically stunning, complex, athletic, dense, and always ideological. He was the ideal man for Cold War communist propaganda, but his works transcend politics precisely because of how creative and innovative he was.

Born in 1927 in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), into a ballet-connected family, Grigorovich seemed destined to build his life on stage. It was at the Kirov Theatre (now the Mariinsky) that he trained as a dancer and took his first steps as a choreographer. His talent soon brought him into the spotlight—not only for his technique and discipline but also for a worldview that, even in his youth, was colossal: ballet as a total language, a mirror of heroism, grand emotion, and collective destiny.

This vision found support and resonance in the Kremlin, and so, in 1964, he was appointed chief choreographer of the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow—a position he held for more than thirty years. Under his leadership, classical dance became an important instrument of propaganda, national pride, and symbolic contest precisely because he understood this game like no one else and made it into a spectacle. Ballets such as the aforementioned Spartacus and Ivan the Terrible, The Golden Age, or his revisions of Swan Lake and Raymonda were captured in several recordings. His most personal work is considered to be The Stone Flower (based on a folk tale from the Ural Mountains, with music by Prokofiev), and it became a showcase for the aesthetic and political power of the Bolshoi, which he presented in Brazil during his first visit to the country in 1986. His style—grand, cinematic, and virile—expanded the physicality of male dancers, reimagined classics through an epic dramaturgical lens, and elevated ballet as a popular, monumental narrative.

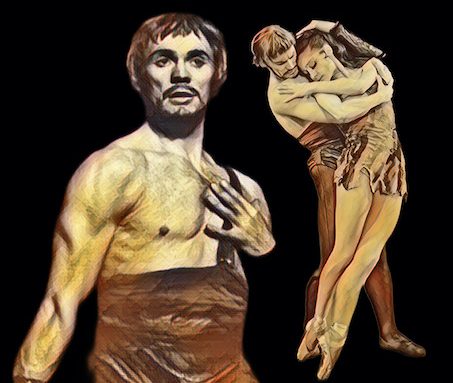

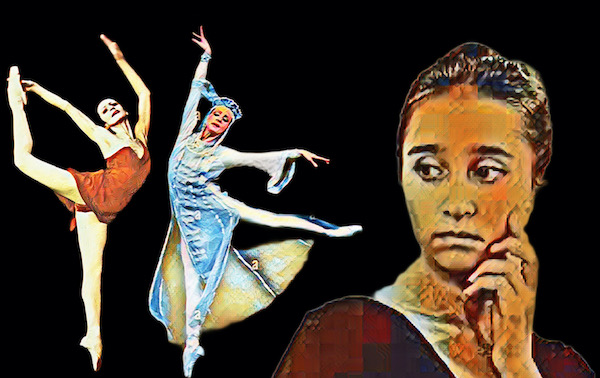

But one does not build an era alone. Grigorovich was also a master of partnerships. He worked with the greatest stars of his generation—and in many cases, shaped them. Maya Plisetskaya, already a celebrated diva when he arrived at the Bolshoi, had an intense and sometimes tense creative relationship with him. Plisetskaya disliked some of his excessively heroic interpretations of female roles, but she also benefited from the visibility his productions provided. With Vladimir Vasiliev and Ekaterina Maximova, the choreographer built a mythical triad. Vasiliev became his definitive Spartacus—muscular, expressive, athletic in the most demanding male role ever created—while Maximova shone in lyrical and emotionally complex roles, becoming one of the choreographer’s favorite interpreters.

But not everything was roses.

Vasiliev—whom many consider an even greater dancer than Rudolf Nureyev, and who would later direct the Bolshoi—led a “rebellion” alongside his wife, Maximova, as well as stars like Maris Liepa and Plisetskaya, who openly criticized Grigorovich’s increasingly autocratic behavior, his monopoly over the repertoire, and what many deemed his heavy, monumental choreographic style. Criticisms from the West, once dismissed as capitalist propaganda, began to be taken more seriously.

Plisetskaya (who died on May 5, 2015) had declined several opportunities to defect to the West out of love and loyalty to the Bolshoi, which she called “the greatest stage there is”—and held a particular grudge against Grigorovich. She accused him of favoring his wife, Natalia Bessmertnova, with the best roles. And although Plisetskaya was already over 40, she remained the darling of Moscow’s ballet-loving public. Nor was she easily intimidated by Grigorovich’s volcanic temperament, having built her own faction of dancers within the company. A veiled reference to Grigorovich in her autobiography reads: “Our servile, and later semi-servile life gave rise to many little Stalins. The mortar of Soviet society was fear… And there were many reasons to be afraid at the Bolshoi.”

After years of growing backstage intrigue at the Bolshoi, Grigorovich was dismissed in 1995 and succeeded by Vasiliev. Despite the drama, Grigorovich still had many loyal members within the company, who organized a strike in his defense.

On a personal level, his deepest connection was with his muse, Natalia Bessmertnova, prima ballerina assoluta of the Bolshoi, and his wife for over 40 years. Bessmertnova was the ideal body for his artistic vision: intense, tragic, endowed with a silent spirituality that Grigorovich explored like no one else. Together, they created definitive interpretations, especially of the female roles he reformulated in the image of a sacralized, almost mystical femininity. Her death in 2008 was a devastating blow to the choreographer, who paid tribute to her in every restaging of his works in the following years. He never remarried.

Grigorovich was also responsible for choreographing the opening ceremony of the 1980 Moscow Olympics and served as a juror at international competitions such as the Benois de la Danse, the “Oscar of ballet.” His fame extended far beyond the borders of the Soviet Union, though he rarely worked abroad, both by personal choice and for political reasons. While he embodied the cultural power of the regime, he was also its victim: facing censorship, surveillance, and being removed from the Bolshoi in 1995 under accusations of creative exhaustion and aesthetic authoritarianism. But even outside the position, his shadow lingered. He returned in 2008, not as a director, but as guardian of the repertoire he had built.

“He saw in us what we couldn’t even see ourselves,” said Denis Rodkin, a principal dancer of the new generation. “He made us feel every moment.” And Nikolai Tsiskaridze, one of the most vocal representatives of the old guard, summed it up: “It was a greatness that cannot be surpassed.”

Grigorovich leaves behind a legacy both ambiguous and inescapable. He was a genius and a tyrant, an innovator and a conservative, a creature of the state and a master of his own will. The way we understand the Bolshoi—its aesthetic, its theatricality, its idea of a nation embodied in dance—almost always passes through him. With his death, the last great chapter of Soviet choreography comes to a close. But his influence, as he once said of movement on stage, “never ends—it only transforms.”

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.