The tragic story of Ivan IV, the first Tsar of Russia, crowned in 1547, whose trajectory provokes such ambivalence that he is known as “the Terrible,” hardly seems like material for a classical ballet. Yet it has become one of the most astonishing works of our time.

Ivan consolidated the Russian state with an iron fist, expanded its borders, centralized power, and — according to chroniclers — gradually lost his sanity, plunging the country into decades of terror. He ordered the execution of nobles, instituted the feared personal guard known as the oprichniki, created a state within a state, and murdered his own son in a fit of rage. Still, he remains an archetype of strength and sovereignty, with a legacy that blends glory and violence, deeply embedded in Russian culture with tragic weight.

His story became powerful material for one of cinema’s most brilliant artists, Sergei Eisenstein, and later, for choreographer Yuri Grigorovich. In 2025, marking both the 50th anniversary of the ballet and the deaths of Grigorovich and the dancer who first embodied Ivan on stage, Yuri Vladimirov, we are reminded how the ballet Ivan the Terrible came to life.

An Iconic Score Transformed Into Ballet

Although Eisenstein’s film was groundbreaking (more on that below), and Ivan IV’s story is astonishing, it is Sergei Prokofiev’s score that acts as the seed binding all three elements into one intelligent and unique work.

The music for Ivan the Terrible was composed between 1942 and 1945 and is considered one of the most intense, somber, and theatrically ambitious works by the Russian composer, with a score that oscillates between the sacred and the brutal, liturgical choral and military march, delirium, and lament.

The film was commissioned during World War II, when dictator Joseph Stalin welcomed the glorification of authoritarian historical figures like Ivan IV — an attempt to legitimize his own repression under the guise of national heroism.

Sergei Eisenstein’s cinematic project was ambitious. Stalin’s authorization came with a catch: the film had to highlight the “spirit of the State” and the need for a strong leader in the face of external threats. The first film, released in 1944, was acclaimed; the second, completed in 1946 but only screened posthumously in the 1950s, was immediately censored. It depicted a darker Ivan, suspicious even of his allies and immersed in near-inquisitorial rituals. Part 3 was never completed. Soviet censors feared the portrayal of Ivan would resonate too closely with Stalin himself.

Prokofiev understood the ambiguous task: he had to portray a feared tsar, but one idealized as a symbol of unity. The result is a score of radical contrasts, filled with irony and pathos. There are moments of Orthodox choral music that evoke Slavic religiosity and create an ancestral atmosphere, such as in the coronation scene. Fanfares and marches depict imperial pomp. But there is also densely dissonant, suffocating music that suggests paranoia and ruin: it emerges in the scenes portraying the persecution of the boyars, the death of Anastasia, and the murder of the son. Prokofiev wrote for a large orchestra but included brutal percussion, piercing woodwinds, tremolo strings, and angular harmonies that give the score an almost expressionistic texture.

With the censorship of Eisenstein’s second film and the project’s abandonment, Ivan’s music fell into obscurity for decades. Prokofiev never created a concert suite as he had with Alexander Nevsky, and the orchestral materials became scattered. After his death, attempts were made to reassemble the fragments into a coherent body for concert performance and recording.

It was choreographer Yuri Grigorovich who, in the 1970s, requested composer Mikhail Chulaki (and later conductor Abram Stasevich, a Prokofiev collaborator) to restructure the score for the Bolshoi ballet. Grigorovich also incorporated segments from other works by the composer, such as Symphony No. 3, based on his censored opera The Fiery Angel, heightening the psychological aspects of the score and accentuating the atmosphere of moral collapse.

In dance, much more than in the film, one can appreciate Prokofiev’s genius in using music as a psychological language. It did not illustrate the scene, but analyzed, distorted, and romanticized the hidden emotions and intentions of the characters. It is music that runs parallel to the text, sometimes in contradiction with it, creating a constant tension between image and sound which, through gesture alone, becomes even more powerful.

“There was no doubt this music could bring stage dance to life. My idea was based on the music, and nothing else,” the choreographer explained about the work. “There was only Prokofiev’s music,” he insisted.

Grigorovich’s ballet brought new life and new political force to Ivan IV, not only because it evokes a controversial historical figure, but because, through music, it continually asks: What is the price of power? And who profits from fear?

A Vehicle of Propaganda — But Genius

Nothing in Russian art existed independently from the State, and because it was virtually used as propaganda for decades, many images of legendary dancers and artists were crafted for this purpose. So, in 1975, when the Bolshoi Ballet premiered Ivan the Terrible, it was no different.

Russia was part of the Soviet Union, deep in the Brezhnev era — a period of relative stability but also political repression and glorification of the imperial Soviet past. Grigorovich found support from the Communist Party to revive this nearly forgotten piece — using Prokofiev’s music and reigniting interest in Eisenstein’s film — because Ivan IV was once again being viewed by political leaders as a symbol of Russian heroism.

Yet, on stage, even if not overtly acknowledged, Grigorovich portrayed Ivan as a distorted mirror of the State itself: paranoid, isolated, compelled to dominate by force, tormented by visions and remorse. It was more than a danced biography — it was, like all great Soviet ballets, a coded message. The sets and costumes were inspired by Russian ancient architecture and fine arts, created by Simon Virsaladze.

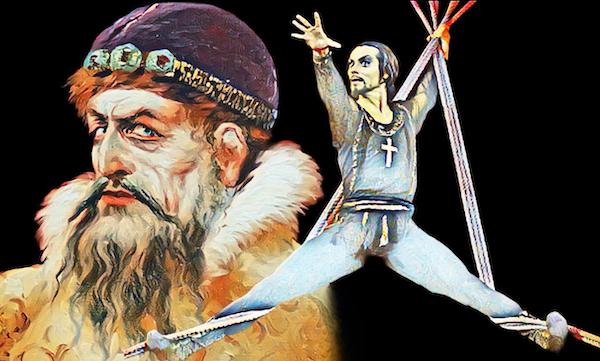

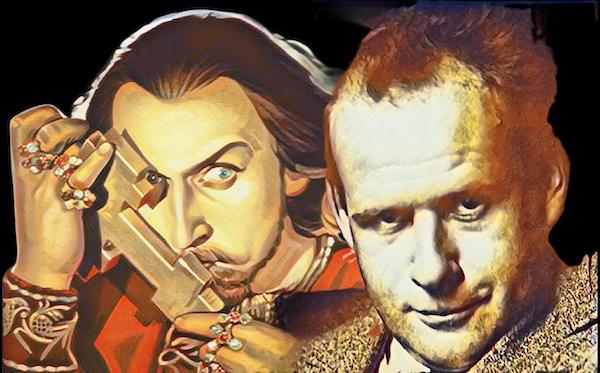

The ballet’s premiere in February 1975 marked one of the Bolshoi’s most grandiose productions of the era. In the role of Ivan was Yuri Vladimirov, who would pass away fifty years later on the same day as choreographer Grigorovich — a nearly poetic coincidence that reinforces the urge to revisit the production’s backstage history. Natalia Bessmertnova, Grigorovich’s wife and the company’s star, portrayed Anastasia, Ivan’s beloved wife, whose death precipitates his descent into suspicion and tyranny. Boris Akimov completed the triangle as Prince Kurbsky, once an ally and now a political rival.

On the ballet’s first tour to Brazil in 1986, Bessmertnova and Akimov reprised their roles, with Irek Mukhamedov dancing the title role. I didn’t see them on stage — I chose to see Spartacus with all three instead — but five years later I saw Ivan the Terrible with the ballerina alongside Alexei Fadeyechev in Paris, and it was one of the most powerful ballets I’ve ever seen in my life. I was familiar with the 1975 filmed version, with the original cast, but this is a ballet that changes radically when seen live. I highly recommend seeing it if possible. That’s because the narrative is driven by Six Bells, which herald plot twists in the characters’ lives with either festive tones or tragic alarms. The solos reveal internal turmoil and dramatic conflict.

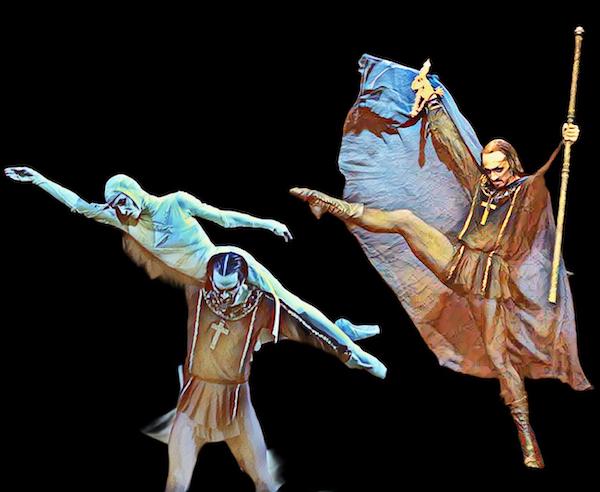

All of it is poetic, distinctive, and impactful, unified in Virsaladze’s vision to construct an oppressive world of shadowy silhouettes, labyrinthine staircases, and thrones surrounded by specters. The choreography breaks from the usual lyricism: rather than a narrative ballet filled with delicacy, Grigorovich created a dance of weight, almost brutalist, with curved bodies, clenched arms, and angular gestures, exposing both physical oppression and psychic agony.

It was precisely this dimension that divided audiences and critics in 1975. Domestically, the work was viewed as an ode to the national spirit, to tsarist glory — a convenient reading for the regime. But outside the Soviet Union, many critics saw in the ballet a glorification of autocracy and state violence. Others, however, admired Grigorovich’s boldness in portraying Ivan as an ambivalent figure: hero and tyrant, visionary and psychotic, a symbol of the burden of absolute leadership. The reception, therefore, oscillated between applause for its grandeur and discomfort with its subtext.

In Russia, the figure of Ivan remains controversial. During the Tsarist Empire, he was remembered as the founder of Muscovy. Under the Soviet regime, he was partially rehabilitated as a precursor of centralizing methods. Today, under Vladimir Putin’s government, his image is once again gaining ground as a model of “strong leadership,” which makes a critical analysis of his presence in popular culture all the more relevant. Works such as Grigorovich’s ballet or Eisenstein’s films cease to be mere historical recreations and become tools for reading the present.

The innovation, both in cinema and dance, lies in the use of art as a psychological analysis of power. Eisenstein, pioneer of Soviet montage, employed claustrophobic framings, intense expressions, expressionist shadows, and shots that resembled medieval paintings. His Ivan was not merely a czar — he was a tormented consciousness, under constant judgment, an Orthodox Macbeth. Prokofiev composed a score that followed this journey like a continuous requiem, opening space for both terror and compassion.

Grigorovich translated that same journey into movement, deepening the bodily language of Soviet ballet. In Ivan the Terrible, the pas de deux is not the moment of beauty, but of confrontation. Ivan’s solitary dance is almost a struggle against invisible forces. The death of Anastasia is not a narrative event, but an internal collapse, choreographed as an implosion. By avoiding sentimentality and embracing ambiguity, Grigorovich distanced himself from more traditional Soviet ballets and approached an expressionist aesthetic.

If Giselle is the Hamlet of ballet, Ivan is the Giselle of male dancers

There is a personal detail in my assessment. Ivan the Terrible demands from its interpreters the same fusion of technical virtuosity and emotional depth that Giselle demands of a ballerina. Ivan is not merely a danced role: it is a lived one, laden with political symbolism, fragmented psychology, and a nearly shamanic force. It is not enough to turn, leap, or support a partner. One must convince the audience that the body is imploding under the weight of the throne, of spilled blood, of paranoia and remorse.

That is why Yuri Grigorovich chose Yuri Vladimirov as the first Ivan — because he embodied both technical and symbolic qualities. Vladimirov was already one of the leading male figures of the Bolshoi in the 1970s, known for his stage presence, technical finesse, and above all, a commanding — almost regal — presence onstage. But the decisive factor was his dramatic talent. Grigorovich needed someone who could transition from glory to degradation on stage, who could sustain an entire ballet with body and gaze, who could move between intimate scenes and large choral blocks with authority. Vladimirov had that concentrated intensity, an expressiveness that didn’t need exaggeration to be devastating. He was a “dancer-actor” of the highest order in the Russian tradition.

In addition to Ivan the Terrible, Vladimirov excelled in other central roles of the Grigorovich era, such as Spartacus, Legend of Love, Swan Lake, and Romeo and Juliet, almost always alongside his wife, the great Nina Sorokina. But it was as Ivan that his image crystallized as an icon of Soviet dance — a role that demanded, simultaneously, fury, delirium, religiosity, and collapse.

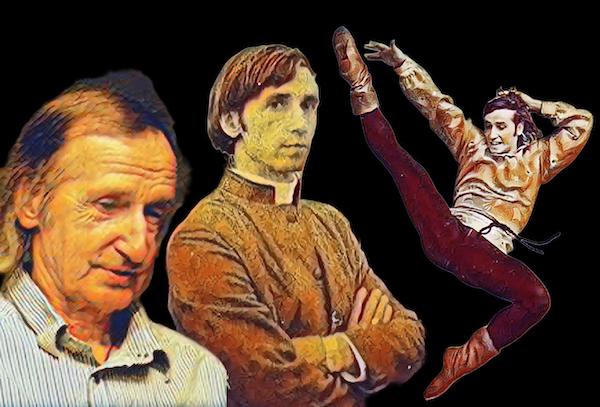

In 1975, the second cast included Vladimir Vasiliev and Lyudmila Semenyaka in the lead roles, and after Vasiliev, other great names assumed the throne of Ivan with different approaches. Mikhail Lavrovsky brought a more introspective, tortured, almost somber interpretation, while Irek Mukhamedov, in the 1980s, incorporated a ravaging, visceral physical energy that amplified the character’s animality and loss of control. More recently, Andrei Uvarov explored Ivan’s emotional vulnerability with precision, especially in the scenes following Anastasia’s death, achieving an interiority that few managed to reach.

In the West, Ivan the Terrible was discovered belatedly — partly because the ballet never officially toured internationally in its early years, due to its political nature and logistical complexity. It was a production designed for the monumental stage of the Bolshoi, with heavy costumes, enormous sets, and a complex musical structure that hindered exportation. Real access to the ballet only came when the Bolshoi began filming and distributing official recordings in the late 1980s and early 1990s. One of those versions — with Mukhamedov in the title role — was shown in festivals and European channels, fascinating critics with its dramatic power and almost operatic intensity.

Compared to other major male roles, Ivan is undoubtedly one of the most complete and challenging. It demands from the dancer an emotional arc that spans love to madness, mystical ecstasy to moral crisis. If Spartacus is an epic tragic hero, Ivan is a tyrant in spiritual decay. The choreography presents immense technical challenges, with long, tense solos laden with symbolic gestures and physical variations requiring an athlete’s stamina and a Greek tragedy actor’s timing.

Ivan the Terrible is, therefore, not merely a repertory piece: it is a rite of passage for the dancer who wishes to prove their artistic reach. And like every great role, it shapes those who dance it — but also reveals what each interpreter has to say about power, fear, and the history we inherit.

Today, fifty years after its premiere and amid the death of its original creators, Ivan the Terrible stands as a historical and artistic document on the dangers of absolute power. It is a work that continues to resonate in times of historical revision, imperial nostalgia, and debates about leadership and authoritarianism. Unsurprisingly, it returns to the Bolshoi’s repertoire in moments of national inflection.

The ballet was staged by the Bolshoi until 1990 and remained dormant until 2012, when it returned to the repertoire permanently. Besides appearing on international tours, the Paris Opera also staged its version in 2004.

By transforming Russia’s most controversial czar into the protagonist of a monumental ballet, Grigorovich reminds us that the stage is often the most faithful mirror of our political anxieties. Ivan the Terrible dances not only about history, but about how we choose to remember it.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.