When he established the foundations of Psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud warned of the danger of so-called “wild analysis” — a term he used to describe the improper use of psychoanalytic tools outside the clinical setting. In other words: if it’s not a session between the individual and the psychoanalyst, it’s not Psychoanalysis — it’s judgment, interference, and it’s wrong. But when it comes to a fictional character like Carrie Bradshaw, the protagonist of one of the most influential franchises in recent pop culture, resisting a psychoanalytic interpretation becomes nearly impossible, especially because she seems to always be self-analyzing.

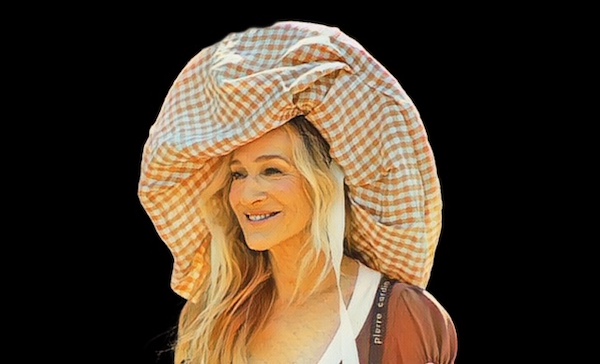

One of the reasons that compels me to pause and propose this reading is the lasting impact Carrie has had on generations who grew up with or fell in love with the series Sex and the City, The Carrie Diaries, the movies, and now the continuation in And Just Like That. In the idealized projections of fans who saw in the four friends — Miranda, Charlotte, Samantha, and Carrie — archetypal versions of the modern woman, it was the neurotic writer who usually generated the strongest identification. Carrie was, for many, the most “relatable.” But if you were always Carrie, how can you explain that your friend, the one who swore she was a Miranda or a Charlotte, also saw herself as Carrie?

Rarely would anyone claim to be Samantha — although she is precisely the one who best withstood the test of time and cultural shifts, as a symbol of empowerment and sisterhood. Qualities that cannot always be so confidently attributed to the other three.

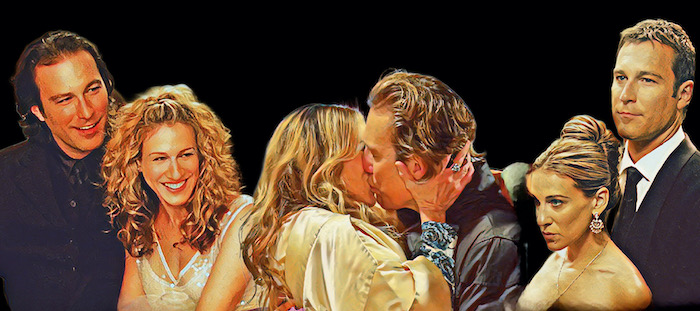

The discomfort we feel in realizing that we don’t enjoy Carrie Bradshaw at 60 the same way we did at 30 makes this “wild analysis” not only tempting — but also relevant. After all, it might help us understand the patriarchal (and psychological) traps that made us root for a toxic man like Mr. Big, believing there was a happy ending in that love story. Or, now, to project onto Aidan — equally imperfect — the promise of a romantic solution for Carrie’s happiness.

Freud gave us the tools to understand, with distance and without judgment, why Carrie Bradshaw may not be a healthy reference for women — and still, paradoxically, represents them so well. Shall we?

1. Childhood and Formation: the wound of maternal abandonment

Although the adult version of Carrie never mentions her family or origins, the prequel The Carrie Diaries revealed that Carrie’s mother died when she was still a teenager. The early maternal absence is a key to understanding Carrie’s difficulty in establishing secure emotional bonds. Freud pointed out that the early loss of a love object can result in what later becomes an “unresolved mourning,” predisposing one to a melancholic personality. In Carrie, this manifests as a constant search for romantic validation — a kind of repetition compulsion in the romantic field.

The father figure, although present in The Diaries, disappears from the Sex and the City universe, being mentioned only once as someone who abandoned her. This fuels a primary abandonment complex, which Carrie projects onto her relationships, especially with Mr. Big: she lives in the tension between wanting to be chosen and fleeing the moment she feels engulfed by a bond.

That’s right. According to Psychoanalysis — especially in its classical formulation — our adult love choices are rooted in the Oedipus Complex, a psychic process that structures our desire based on our earliest relationships with parental figures. For women, it is common for the father figure — or more precisely, the function that figure occupies in the unconscious — to play a decisive role in how we form emotional attachments. Unconsciously, we seek in romantic relationships to reenact or repair unresolved aspects of this childhood dynamic. When Carrie Bradshaw chooses Mr. Big as her “great love,” we may infer that she is trying, repetitively and compulsively, to fulfill an unconscious expectation of being chosen, valued, or recognized — perhaps by a father who never symbolically appeared in her story.

This pattern repeats itself in virtually all of Carrie’s romantic relationships. Berger, Aidan, Petrovsky, Big — all of them, at some point, represented what Lacan would call the objet petit a: a kind of lure of desire, always out of reach, promising an emotional completeness that never materializes. Men who seemed to offer Carrie full love, but who, in practice, were either emotionally unavailable or required her to mold herself into something she was not. The repeated choice of such figures suggests a desire structured around lack: Carrie loves what is always one step ahead — just out of reach enough to keep alive the illusion of wholeness. This is not a personal flaw, but a symptom — an unconscious way of sustaining the search for an ideal love that, deep down, preserves the logic of frustration. Instead of breaking this cycle, Carrie aestheticizes it: she turns the wound into text, the pain into glamour, the lack into a lifestyle. And that’s why so many women identify with her: Carrie embodies the contradiction between the desire to be loved for who we are and the urge to win over the very person who insists on seeing us in fragments.

If you rooted for these romances, don’t feel guilty — or neurotic. Cinema and television culture are built precisely around unstable narratives, full of ups and downs, suspense, and emotional twists. It’s natural for us to get involved, to project, to suffer along. The only thing worth remembering is that no, Carrie Bradshaw is far from being a woman free of trauma, neuroses, or unconscious repetitions. And that’s exactly what makes her so relatable.

2. Performative Narcissism and Writing as Defense

Carrie writes about sex and relationships, but her columns almost always revolve around herself. Of course, this happens because she’s a columnist and her texts are meant to be personal — after all, she is the protagonist of the story she tells.

On the other hand, this constant focus on the self suggests what Psychoanalysis calls defensive secondary narcissism: a mechanism through which the subject places themselves at the center to preserve their psychic integrity in the face of emotional fragility. For Carrie, writing functions as a way to symbolize traumatic reality — an attempt to control the narrative of her own life and simultaneously shield herself from the chaos of the unconscious.

This narrative compulsion also acts as a defense against symbolic castration. Writing is a way of taming the uncontrollable, an attempt to stitch the wound with words, episode after episode, trying to give meaning and shape to what seems irreparable.

Now, there is indeed an extremely narcissistic aspect in Carrie, who rarely listens to her friends’ pain. For example, when Miranda asked for help after falling in her apartment and needed someone to help her up, Carrie sent Aidan instead because she had another commitment — an act that can be seen as emotional distancing. On another occasion, when her friends rightly criticized her, Carrie responded by saying they weren’t being empathetic toward her, deflecting responsibility and avoiding confronting her own shortcomings.

Perhaps the most emblematic example of this narcissism appears in the episode where Carrie faces financial difficulties and, instead of taking responsibility for her choices — like overspending on shoes while postponing buying her own apartment — she asks Charlotte for financial help, judging her friend as insensitive for not rescuing her (which Charlotte ends up doing). This moment reveals not only Carrie’s emotional and financial dependence but also an unrealistic expectation to be centered and cared for by her friends, even if that compromises their autonomy.

Carrie is a good friend with a genuine capacity for affection and loyalty, but she also exhibits many challenging moments, where ego and the need to control her personal narrative outweigh empathy and reciprocity.

3. Romantic Relationships: Projections, Compulsions, and Fear of Intimacy

We’ve already discussed how Mr. Big is the epicenter of Carrie’s romantic fantasy. He represents the unattainable “Big Other” — a phallic figure loaded with prestige, indifference, and mystery. Carrie invests emotionally in Big not for who he really is, but for who she wants him to be: a mirror that legitimizes her and fills an internal void. Throughout the series, her relationship with Big unfolds as a dramatization of the hysterical fantasy, where the subject positions themselves as lack or absence for the Other in the hope of being desired and, thus, completed.

Aidan, on the other hand, represents the possibility of real, everyday, secure love. However, it is precisely this safety — this stable intimacy — that becomes intolerable for Carrie at times. The closeness Aidan offers threatens to unveil her own anguish and the unglamorous identity stripped of the neurotic persona she has built. Freud would speak here of a refusal of reality in favor of neurosis: Carrie sabotages Aidan because he represents the risk of dissolving the fantasy that supports her psychic structure.

In And Just Like That, the reunion with Aidan seemed to point toward a possible repair of that dynamic — an invitation to finally appreciate a love not based on absence or idealization. However, the writers, staying true to the series’ dramatic logic, once again turn Aidan into an “unavailable” figure, now due to obligations with his children. This keeps the tension alive by shifting to him the position of the unattainable man that for years belonged to the late Mr. Big. Thus, Carrie declares him “the great love of her life,” but the repetition of the pattern makes it clear that more than a real person, Aidan embodies a psychic function tied to desire and lack.

The compulsive repetition of this pattern — investing in men who are, in one way or another, emotionally unavailable — is a deep psychic symptom connected to the neurotic structure. For Carrie, this dynamic works as an unconscious strategy to preserve a comfort zone within frustration. She loves what is always just out of reach because, paradoxically, it protects her from full exposure to intimacy — that radical vulnerability that would force her to confront not only the other, but especially herself.

This fear of intimacy is linked to a defense against what Freud called “symbolic castration,” that is, the acceptance of limitations and losses that are part of real emotional bonds with others. For Carrie, accepting emotional completeness would mean acknowledging her own wounds, conflicting desires, and deep insecurities — something the series’ narrative, even in its more mature moments, rarely allows her to do without defending herself through irony, humor, or escapism.

Moreover, the choice of partners who want to change her or who fail to see her as a whole person can be read as an attempt to maintain indirect control over the relationship, preserving the illusion of autonomy. This control is illusory, as it ends up repeating patterns that perpetuate her own sense of helplessness and neediness. It is the “escape from freedom” described by psychoanalyst Rollo May: the subject prefers the familiar suffering of repetition to the anxiety of the newness that freedom brings.

Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha, each with their own forms of love and challenges, function in Carrie’s life as mirrors and counterpoints. Miranda, more rational and pragmatic, reflects the most vulnerable and denied part of Carrie, who rejects emotional maturity in favor of desire and fantasy. Charlotte, idealistic and traditional, represents what Carrie both rejects and envies — the possibility of a happiness that seems stable but comes with its own psychic costs. Samantha, in turn, embodies unrestrained sexual freedom, challenging the neurosis and fear of intimacy that Carrie carries, even though Carrie rarely manages to fully integrate this freedom.

At the core, the identification that many women feel with Carrie lies precisely in this complexity and contradiction. She is not the fulfilled and liberated woman pop culture often sells, but a subject in permanent tension, marked by conflicting desires, flaws, relapses, and an eternal search for something that never quite arrives. This humanity — with all its weaknesses and failures — is what makes her feel so close and, at the same time, so frustrating to those who follow her journey.

4. Friendship as a place of sublimation and transference

Female friendships function as transferential supports — both in a therapeutic and narcissistic sense. They are mirrors and emotional cushions.

- Charlotte represents the moral superego and the traditional romantic ideal. Carrie gets irritated by her naiveté, but also envies her. Charlotte is, in a way, what Carrie tries to avoid becoming, but whose sweetness and faith in love move her. Their classic confrontation — “I believe in love at first sight!” “You believe in it because you’ve never been hurt!” — reveals an internal split in Carrie between skepticism and hope.

- Miranda is the rational ego, the principle of reality. She acts as a cynical counterpoint to Carrie’s emotional impulsiveness. But Carrie rarely embraces Miranda’s point of view — she tolerates it. This shows how Carrie relates to her friends ambivalently: as partial mirrors. She accepts their presence as long as she’s not confronted with her contradictions.

- Samantha is the only one who escapes Carrie’s emotional logic. Samantha is sexual potency, full autonomy, and absence of guilt. The tension between Carrie and Samantha lies in the fact that the latter doesn’t want to be understood or narrated — she simply exists. Carrie never manages to integrate Samantha as a model of womanhood; she admires her as one admires what is unattainable.

In And Just Like That, Samantha’s absence is treated as mourning. The new friends (Seema, Lisa, Nya) are introduced as symbolic substitutes, but none carries the same structural weight. Carrie needs to step outside herself to reinvent who she is, but the series shows how this process is more difficult with maturity. Seema, in particular, functions almost like an informal analyst: it is with her that Carrie confronts the possibility of being alone — and being okay with it.

5. The shoe-object as phallic fetish

Carrie’s fascination with shoes — especially Manolo Blahniks — is not merely about fashion. It is fetishistic in the Freudian sense: the shoe occupies the place of the symbolic phallus — that which is lacking but can be staged. She declares, “I like the shoe, it gives me something men don’t give me.”

Carrie uses shoes as instruments of power, of identity affirmation, of desire. When she walks, she performs. The loss of a shoe (as in the episode A Woman’s Right to Shoes) is more than an anecdote: it represents a threat to her symbolic value — to what she believes protects her from social castration. By reaffirming herself as worthy of a new pair, she reaffirms her place in the world.

6. Aging and the decline of the romantic fantasy: the displacement of desire

In And Just Like That, time finally takes its toll. Carrie is confronted for the first time with losses that cannot be aesthetically sidestepped: Mr. Big’s death, menopause, loneliness, and the decline of her cultural relevance. Her body changes, her libido changes, her social circle frays. For the first time, she no longer knows exactly who she is — and, more importantly, she can no longer write the same way. This crisis is symbolic: when language fails, the self also falters. Writing had always been the way Carrie embroidered meaning onto her experiences; without it, all that remains is the void once covered by words, shoes, and stories.

The renewed relationship with Aidan seemed to promise a sort of “alternative happy ending,” as if the series offered the chance to rewrite the story with maturity. But what follows is not a mistake, betrayal, or passionate drama — it is a structural impossibility. Aidan now has children, responsibilities, and boundaries. Carrie no longer occupies the center of anyone’s life — and that, unlike what it might have seemed years before, is no longer the end of the world. The narrative, instead of following a logic of repair, teaches a kind of gentle resignation. Carrie begins to accept that some stories do not conclude, some people don’t stay, some desires simply change shape.

Of course, as previously mentioned, this new Aidan also takes on the symbolic place of unavailability that for so many years belonged to Mr. Big. But the difference lies in Carrie: now she chooses to walk away. She doesn’t implode the relationship on impulse, she doesn’t martyr herself. She simply realizes it’s no longer viable — and that, in itself, is a gesture of maturity.

This displacement of desire — from romantic love to something more subtle and internal, like serenity, space, autonomy — represents a rare kind of growth for female protagonists in pop culture. And paradoxically, it’s exactly this that has alienated part of the audience. Carrie seems to have lost her spark, her glittering neurosis, her dramatic instability. When she asks, “What have I gotten myself into?”, many interpret this as a sign of boredom, of settling. But perhaps the answer is another: she’s finally stepped into real life.

The uncomfortable truth is that emotionally stable people don’t make for great drama. In the classic hero’s journey, you need conflict, loss, and transformation. A balanced subject navigates the plot with fewer jolts — and to the viewer, this can feel like a loss of magnetism. We find this new Carrie strange because, perhaps, we still need the comforting chaos of her neuroses to assure ourselves that we’re alive, that we are still who we used to be. But we, too, are changing — and she, in a way, was simply the first to admit it.

7. Why do so many women identify with Carrie Bradshaw?

Carrie’s strength doesn’t lie in perfection — but in contradiction. She makes mistakes, is selfish, makes bad choices, hurts others, but keeps trying. Carrie’s appeal lies precisely in this narcissistic vulnerability, which mirrors the contemporary feminine condition: wanting everything, not knowing how, not knowing if it’s allowed. She is the portrait of a subject in search of herself, using aesthetics, humor, and friendship as symbolic containment.

Carrie also legitimizes female desire in all its forms: the desire for love, for sex, for freedom, for recognition. She gives voice to real doubts — “Why didn’t he call?”, “Can I forgive?”, “Am I enough?” — and offers a language where, before, there was only silence or guilt.

She is not a role model; she is a mirror. That is why she endures.

Carrie Bradshaw is a modern hysteric: not in the vulgar sense of the term, but in the deeper psychoanalytic meaning. She lives on the edge between desire and language, between jouissance and lack, between idealization and collapse. Her writing is the thread that keeps her tied to the world. Her relationships, her friends, her shoes, her doubts — all are part of a psychic montage whose aim is not to heal, but to continue.

Carrie is the disheveled ego of an entire generation.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.