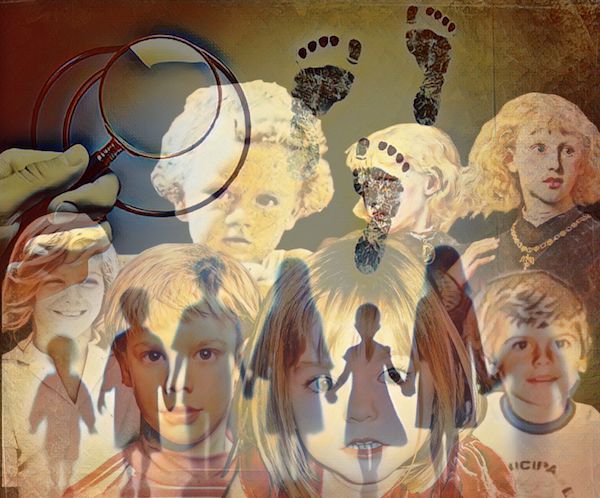

Stories of missing children cause more than mere commotion — they open an ancestral wound, a trauma that transcends cultures, eras, and geographies. It’s not just about public safety or justice: it’s about what we most fear losing — innocence, continuity, the idea of a future.

Why do these stories touch us so deeply?

From a psychological perspective, the disappearance of a child represents more than the loss of a life — it activates ancient triggers. The figure of the child symbolizes purity, the future, and continuity. When a child goes missing, it’s not just the individual who is lost: it’s the collective hope that is broken.

Freud would associate this dread with the primal trauma of loss and helplessness, while Jung might view it as the violation of the “divine child” archetype — a disruption of psychic order. For adults, this fear strikes directly at the protective instinct. For society, it opens cultural wounds, such as our powerlessness in the face of evil and the questioning of institutional effectiveness.

The outcry, the media repetition, and he obsession with clues or theories partly reflect a desperate attempt to restore a sense of control. As if finding the whereabouts of the child could also regain our faith in the world’s order.

Childhood as a symbol: What is at stake when a child goes missing?

Few human tragedies provoke such an overwhelming response as the disappearance of a child. Amid collective fear, protective impulse, and the dark fascination of mystery, emblematic cases transcend centuries — from the medieval princes in the Tower of London to Madeleine McCann’s face projected on airport billboards. It’s not just a life that is lost or silenced: it’s the illusion of safety that collapses.

This reaction, though it may seem modern, traces back to the deep history of power, royalty, family identity, and later, media and public opinion.

The Princes in the Tower: the disappearance that shaped England

In 1483, the young princes Edward V, age 12, and his younger brother Richard, Duke of York, age 9, sons of the late king Edward IV, were taken to the Tower of London supposedly for protection and for Edward’s coronation preparations. What followed, however, was a political coup.

Their uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, initially appointed as Lord Protector, later declared that Edward IV’s marriage had been invalid and that his sons were illegitimate. With this claim, Richard took the throne as Richard III. Shortly thereafter, the two boys disappeared from the Tower. They were never seen again.

At the time, rumors spread that the princes had been murdered to secure Richard III’s claim to power. Over the centuries, multiple theories emerged: that Richard ordered their deaths, that other rivals like Henry Tudor (who would become Henry VII) were responsible, or that one of the boys may have secretly survived.

In 1674, during renovations at the Tower of London, the skeletal remains of two children were found hidden beneath a staircase. King Charles II ordered the remains buried at Westminster Abbey as those of the princes, but no conclusive analysis was ever done — and to this day, their identity remains uncertain. The possibility of modern DNA testing is still controversial, partly due to the involvement of royal tombs.

The disappearance of the princes lies at the heart of the dark legend of Richard III, whose image was heavily influenced by Shakespeare’s eponymous play, written about a century later, which portrayed him as an ambitious and murderous villain.

The case of the Princes in the Tower continues to fascinate the public with its tale of power, lost innocence, and unsolved mystery. It is often cited as one of the first and most famous child disappearances in recorded history, with enduring political and cultural resonance even after 542 years.

The “Crime of the Century”: the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby

Almost 450 years later, another case would shock the world: the kidnapping and murder of the baby son of American aviation hero Charles Lindbergh.

On March 1, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., son of the famed aviator, was taken from his crib and immediately became front-page news. The baby was only 20 months old when he vanished from his room at the family’s home in Hopewell, New Jersey.

That night, the nanny found a ladder propped against the window of the baby’s locked bedroom. The child was gone, and next to the window was a ransom note demanding money in exchange for the child’s life.

The news caused global shock. Charles Lindbergh was a household name for having completed the first nonstop solo transatlantic flight, and the abduction of his son stirred deep public emotion and collective fear of crimes against children.

For months, the parents followed the kidnappers’ instructions, who demanded a ransom of $50,000 — a massive amount at the time. However, in May 1932, the child’s body was found buried just miles from the house, revealing that he had likely been killed shortly after the abduction.

The investigation focused on Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant arrested in 1934. He was accused of kidnapping and killing Charles Jr. Hauptmann denied the charges, but evidence such as ransom money found in his possession and forensic links to the ladder used in the kidnapping led to a high-profile trial.

The trial, broadcast across the country, became one of the first major true-crime media spectacles in American history, shaping public perception of the case. Hauptmann was convicted and executed in the electric chair in 1936.

Still, the case left behind decades of unanswered questions and conspiracy theories — doubts about Hauptmann’s true guilt, the possible involvement of accomplices, and accusations of media manipulation. The case also led to the creation of the “Lindbergh Law”, which imposed harsher penalties for kidnapping in the United States.

When the Media Enters the Story: Etan Patz and the Children on Milk Cartons

On May 25, 1979, Etan Patz, a boy just 6 years old, mysteriously disappeared while walking alone for the first time to the bus stop near his home in the SoHo neighborhood of New York City. It marked the beginning of a shift in public and governmental attention to missing children in the United States.

Etan lived with his parents and siblings, and that day his mother walked him to the corner of the street, where he was to catch the school bus on his own for the first time. When the bus arrived, Etan was no longer there. He had simply vanished.

The case caused a huge public outcry and was one of the first to receive extensive coverage by the American media. His photo was widely circulated on posters, TV programs, and newspapers, sparking a wave of solidarity and growing concern about child safety.

The search for Etan lasted for years. For a long time, the case remained a mystery, with no concrete leads. His mother, who had been warned by experts not to let him walk alone at such a young age, turned her grief into activism, becoming one of the earliest and strongest voices in the fight for missing children’s rights.

The case only reached a judicial conclusion nearly 30 years later, in 2012, when Pedro Hernandez, a former employee at a nearby convenience store, confessed to kidnapping and killing Etan Patz in 1979. Hernandez stated he had a mental disorder and that the crime was driven by a violent impulse.

In 2015, Hernandez was convicted of second-degree murder and is currently serving a life sentence.

Etan Patz’s disappearance marked a turning point in U.S. legislation. It was the first case of a missing child to have their photo printed on a milk carton, helping to popularize public awareness campaigns for missing children. It was also instrumental in the founding of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children in 1984, which became a leading institution in protecting and investigating such cases.

Furthermore, May 25th, the date of Etan’s disappearance, was declared National Missing Children’s Day in the United States.

Madeleine McCann: The Most Media-Covered Case of the 21st Century

On May 3, 2007, Madeleine McCann, a 3-year-old British girl, mysteriously disappeared while on vacation with her family in Praia da Luz, Portugal. The case quickly drew global attention, becoming one of the largest missing child investigations in recent history.

Madeleine was staying with her parents, Kate and Gerry McCann, and her two younger twin siblings in a holiday resort apartment in the Algarve. On the night of the disappearance, while the parents were dining at a nearby restaurant with friends, Madeleine was sleeping in the apartment with her siblings. The parents checked on the children regularly, but when they returned for the last time, Madeleine’s bed was empty.

The disappearance triggered a massive international response involving Portuguese and British police, as well as security agencies from several countries. The media followed the case intensely, and Madeleine became a global symbol of missing children — but the situation became increasingly complex due to several factors:

- The initial investigation by Portuguese police was criticized for its shortcomings, including accusations that the parents were treated as suspects.

- Numerous theories and suspects emerged over the years, including reported sightings of the girl in various countries, none of which were confirmed.

- In 2020, German police identified a suspect: Christian Brückner, a convicted pedophile and sex offender who was in the area at the time and had a history of crimes against children. German authorities believe he may be directly involved in Madeleine’s disappearance and possible murder.

Despite the investigations and global attention, the case officially remains unsolved, with neither the child found nor definitive answers about what happened that night.

The disappearance of Madeleine McCann exposed the fragilities and challenges of international investigations, the media’s role in shaping public narratives, and the profound pain and complexity families face in the absence of answers. Neither the Portuguese police, Scotland Yard, nor German authorities have been able to solve the mystery that persists 18 years later.

Moreover, the case spurred changes in protocols for search and response efforts in missing child cases, including enhanced measures for prevention and raising awareness about child safety.

And in Brazil? From the Carlinhos Case to the Boy Evandro

In Brazil, three cases of missing children have become especially emblematic.

The earliest is that of Carlos Ramires da Costa, known as Carlinhos, who was 10 years old when he disappeared on August 2, 1973, from his home on Rua Alice, in the southern zone of Rio de Janeiro. He was one of seven children of Maria da Conceição Ramires da Costa, a homemaker, and João Mello da Costa, an industrialist and owner of the pharmaceutical company Unilabor, in Duque de Caxias.

On the night of the kidnapping, Carlinhos was watching television with his mother and some of his siblings when the house’s power was cut. A young Black man, wearing a red shirt and sporting a black power hairstyle, broke into the residence, asked for the youngest child in the house (Carlinhos), locked the mother and siblings in the bathroom, and fled with the boy.

Before leaving, the kidnapper left a note demanding a ransom of 100,000 cruzeiros (a very high amount at the time). However, although the ransom was prepared by the father, and police were present in disguise, no one showed up to exchange the money for the boy. Carlinhos was never found. Both the mother and father were considered suspects at different points, but never formally charged.

The Carlinhos Case remains a mystery involving suspicions of a crime of passion, financial motives, a possible crime planned by someone close, manipulations, false leads, and heavy involvement from the press and police. To this day, Carlinhos’s whereabouts remain unknown, and the case is remembered as one of the most intriguing and controversial in Brazilian crime history.

In 1986, Pedro Rosalino Braule Pinto, known as Pedrinho, was kidnapped just hours after being born at the Santa Lúcia Hospital, in Asa Sul, Brasília. The woman responsible for the abduction, Vilma Martins Costa, posed as a nurse and took the baby away under the pretense of needing medical exams. She registered the child under a different name, Osvaldo Martins Borges Júnior, and raised him in Goiânia, where she had also kidnapped another girl, Aparecida Fernanda Ribeiro da Silva, raising them as siblings. The case remained unsolved for many years until 2002, when Gabriela Azeredo Borges, granddaughter of Vilma’s ex-husband, noticed similarities between Osvaldo and Pedrinho’s biological parents after seeing photos on the Missing Kids website. Following her suspicion, the police were contacted and, through DNA testing, confirmed that Osvaldo Martins Borges Júnior was in fact Pedro Rosalino Braule Pinto. In 2002, Pedrinho was reunited with his biological parents, Jayro Tapajós and Maria Auxiliadora Braule Pinto, in Brasília.

Vilma Martins Costa was sentenced in 2003 to 15 years and 9 months in prison for the crimes of child abduction, identity fraud, and swindling. She was granted parole in August 2008 after serving a third of her sentence. Today, Pedro Rosalino Braule Pinto is a criminal defense lawyer and has represented clients such as former soccer player Robinho, convicted of rape in Italy, and former senator Aécio Neves, investigated in the Operation Car Wash scandal. Pedrinho is married and the father of two children.

Finally, the most shocking case of all: the case of the boy Evandro. In April 1992, Evandro Ramos Caetano, only six years old, disappeared in Guaratuba, on the coast of Paraná, after leaving home to meet his mother at the school where she worked. He had returned home to fetch a forgotten toy but was never seen again. The family reported his disappearance, and four days later, his body was found in a wooded area, showing signs of violence and missing body parts. The investigation quickly pointed to a possible black magic ritual involving well-known locals, including Beatriz and Celina Abagge, mother and daughter, and three others: Osvaldo Marcineiro, a spiritual leader; Davi dos Santos Soares, a craftsman; and Vicente de Paula Ferreira, a painter. The case became popularly known as “the Witches of Guaratuba.”

In 2021, recordings emerged showing that the convicted individuals had been tortured by police to obtain confessions—evidence that had not been presented in earlier trials. As a result, in 2023, the Court of Justice of Paraná overturned the convictions, recognizing that the confessions were obtained through torture, marking an important milestone for justice in Brazil. However, to this day, the case lacks a definitive and uncontested conclusion as to who actually killed Evandro.

These three cases not only moved the nation but also exposed the fragility of child protection systems and the importance of responsible media coverage.

The Pain of Loss and Suspicion

Parents or guardians are often the first suspects in cases of missing or deceased children due to a combination of investigative, statistical, and cultural factors. First, their close proximity and daily access to the child make them natural focal points for authorities. The logic of police work, based on historical patterns and criminal statistics, suggests that in most cases of child violence, the perpetrator is someone from the victim’s intimate circle—often a direct relative. Furthermore, parents are the first to give statements, and any contradiction, no matter how small, can be interpreted as a sign of guilt, even if it stems from trauma, stress, or emotional confusion.

Social and media pressure for quick answers also contributes to investigations initially targeting family members. The public behavior of parents—whether they appear too calm, cry too much, talk too much, or too little—is constantly judged, even though grief and shock manifest differently in different people. There is also the influence of previous high-profile cases involving parents or caregivers, creating a kind of “unconscious template” that reinforces suspicion in similar situations. This shapes not only public imagination but also pressures authorities to scrutinize the family more rigorously, which can sometimes lead to mistakes.

In some cases, such as that of Evandro in Brazil, suspicion toward the parents arose even without concrete evidence and later proved unfounded—an outcome of questionable or manipulated police procedures. There are also situations where the parents are not directly guilty but become indirectly involved or suffer the consequences of investigative errors. The major challenge is managing the need to quickly identify a culprit in the face of the horror of a crime against a child.

The Fascination with Tragedy: Children and the Imaginary of Violated Purity

The public reaction to child disappearances stems from a deep emotional place—not only because of the suffering involved, but because such events are perceived as something that should not happen. Children are seen as innocent, pure, and protected. Their disappearance represents a brutal rupture in the order of the adult world.

That’s why these cases become so symbolic, explored in books, series, podcasts, and films. That’s why we remember names, dates, and faces. And that’s why, even centuries later, we still ask ourselves: What happened to Edward and Richard? To Madeleine? To so many other children whose stories echo like open wounds.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu