My analyst could probably explain more precisely why, among all the content I consume — fantasy, drama, suspense — dystopian stories dealing with psychological oppression are what disturb me the most. Maybe it’s the corporate world experience, but I confess I kept my distance from Severance until I had to check it out after Variety named it the show that will dominate the Emmys in September. Readers of this blog know I’d rather see Andor win, but I couldn’t move forward without understanding what Severance is really about.

Since its debut, the series has sparked debates about corporate ethics, identity, and free will. Created by Dan Erickson and partially directed by Ben Stiller, this Apple TV+ production begins with an absurd premise — a surgical separation between personal and professional memory — to deliver a sharp and unsettling critique of labor, subjectivity, and alienation.

The origin of the idea

Dan Erickson wrote the original script as a critique of dehumanization in the workplace. He had worked in administrative jobs that made him fantasize about a real separation between personal and professional life. What started as a satirical premise gained darker and more philosophical layers, drawing the attention of Ben Stiller, who saw in it a chance to create a visually claustrophobic and emotionally precise piece.

The series draws influences from 1984 and Brazil to Black Mirror and Kafka, while also evoking Foucault’s critique of institutional surveillance and the Cartesian split of the self. But it is also a contemporary allegory of burnout, extreme capitalism, and the fragmentation of the self in times of hyperproductivity.

Plot and structure

In Severance, employees at Lumon Industries voluntarily undergo a procedure called “severance,” which splits their memories into two spheres: the “outie” (life outside the company) and the “innie” (life inside the office). The stated goal is to help employees achieve work-life balance. But what happens is the opposite: the creation of two distinct entities within one body, each completely unaware of the other.

The protagonist, Mark Scout (Adam Scott), works in the Macrodata Refinement (MDR) division, where, alongside his colleagues Helly, Dylan, and Irving, he spends his days looking at numbers on a screen and “refining” them based on feelings — fear, discomfort, euphoria. None of them knows what the numbers mean. No one even knows the purpose of their own work.

What do the severed employees actually do?

In MDR, employees classify numbers based on the subjective emotions they provoke. This seemingly meaningless activity reflects the complete alienation of the worker. Labor ceases to be a means and becomes an end in itself — a liturgy without transcendence. The lack of clarity about the product of their work makes the activity cruel: the individual works without knowing the consequences of their labor.

Besides MDR, there are other obscure divisions within Lumon:

- Optics and Design (O&D): shrouded in mystery and secret maps.

- Wellness: a therapeutic room where innies receive compliments about their outies as a form of pacification.

- Break Room: a psychological punishment room, where employees must repeat phrases of guilt.

- Testing Department: seen in the second season, seems focused on cognitive and emotional experiments, including attempts to activate suppressed memories.

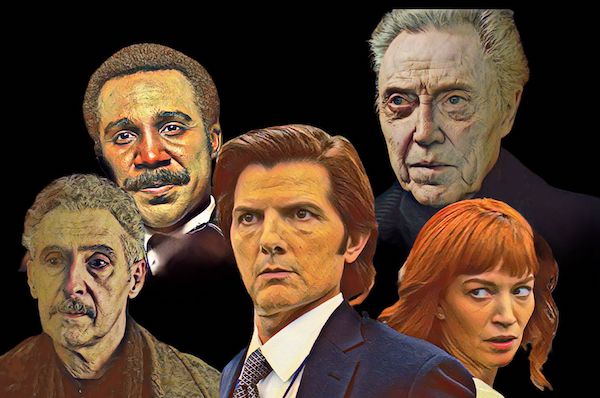

A finely tuned cast

The greatest praise goes to the cast, whose performances stand out for their quality and for the presence of big-screen and TV veterans. At the heart of the story is Adam Scott, who plays Mark Scout with impressive subtlety, balancing the emotional restraint required for a character split between two realities. Known for his comedic roles in Parks and Recreation, Scott surprises by exploring a dramatic, introspective side that captivates viewers across both seasons.

Britt Lower, as Helly R., brings visceral, combative energy, reflecting her character’s resistance and frustration in the face of the oppressive Lumon Industries. Her intense, emotionally charged performance is a cornerstone of the show’s tension. Veteran actor John Turturro, renowned for iconic Coen brothers films like The Big Lebowski and Barton Fink, lends a commanding and nuanced presence to Irving Bailiff, whose personal story and motivations add layers of mystery and complexity to the narrative. Another standout is Tramell Tillman, who plays Milchik, Mark’s supervisor, with a compelling mix of authority and vulnerability, creating a memorable and ambiguous figure.

In addition to this core cast, Severance’s second season features a special guest appearance by the legendary Christopher Walken, whose entrance into the story adds both weight and mystery. Walken, known for his long and distinctive career in cinema, raises the production’s level even higher with his singular performance, helping solidify Severance as a series that impresses not only through storytelling but also through acting excellence. These performances distinguish the show in today’s television landscape, combining talent, emotional depth, and charisma, and helping to construct a rich and layered fictional universe for viewers to explore.

Psychoanalysis and the split self

The severance procedure literalizes Freud’s concept of psychic division. The subject ceases to be a cohesive entity and becomes multiple: one part — the innie — lives in perpetual work-prison, without sleep, memory, or past identity. This split mirrors the narcissistic cleavage of the ego: each half of the individual becomes the other’s object.

Lacan’s mirror stage theory is relevant here. The innie is a kind of split self who lacks access to the “mirror” — the totalizing image of themselves. They live without the symbolic, without inscription into the outside world. Their Other is the outie — a godlike, unreachable entity.

Helly, for example, expresses revolt from the very beginning. Her innie attempts suicide — a cry of autonomy from an identity that wasn’t supposed to exist. It’s an act of affirmation: “I exist, even if I’m not meant to live.” This shows that human identity cannot be suppressed without consequences. Subjectivity resists.

The relationship between Dylan and his son — whom he sees briefly thanks to a device allowing temporary innie control over the body — is one of the show’s most emotional moments. He realizes that his existence has been amputated from fatherhood. This represents a core conflict of the contemporary subject: the desire for presence versus captivity under the logic of productivity.

The cult of Kier Eagan

Lumon is not just a company. It presents itself as a corporate religion, founded by Kier Eagan. His tenets are repeated like mantras, and images of the founder are scattered through the hallways. The cult of Kier and the “Eaganist principles” functions as ideological control: a form of indoctrination that strips employees of any impulse toward questioning.

This corporate mythology echoes Foucault’s studies on disciplinary institutions. Lumon operates like a panoptic prison: bodies are controlled, schedules are strict, and emotions are monitored. The wellness room, the break room, and incentive dances are mechanisms of punishment and reward disguised as care.

Who are the antagonists?

The main antagonist is the structure of Lumon itself. But there are specific figures who embody it:

- Harmony Cobel: Mark’s direct supervisor, who pretends to be his neighbor in the outside world. She believes in severance as a messianic project.

- Milchik: the operational enforcer who punishes and monitors workers, often with a mask of empathy.

- Natalie and the Eagans: they represent the corporate elite. It’s revealed that Helly is actually Helena Eagan — a Lumon heiress sent in as a volunteer to legitimize the project. The innie revolts against her own body, which carries the blood of domination.

Who are the non-severed outies?

Though most of the top executives are sereved, there are clear signs that many leadership members retain full memory. Severance is applied selectively: used on bodies that must be shaped, but not on those in power.

Helena Eagan is the clearest example: her outie is fully aware of the innie’s experience and sees it as a marketing tool. The dissociation isn’t a mistake — it’s the plan. A dominant class dissociates the bodies it exploits and strips them even of the right to remember.

What does Lumon want?

The series hasn’t given a final answer yet, but clues suggest that Lumon aims to expand severance technology into other areas of human life: judicial punishment, education, and military control. The idea is to use identity-splitting as a method of domination and mass conditioning.

Ultimately, Lumon is an allegory for systems that seek to turn humans into tools. By separating mind from body, past from present, identity from function, it creates the ideal worker: obedient, memoryless, emotionless, with no claim to rights.

The 2025 favorite for Best Drama Series

According to Variety, Severance is the top contender for the Emmys in September. It delivers a scathing critique of late-stage capitalism, but goes beyond economic allegory. It asks: What does it mean to be a person? What happens when our consciousness is hijacked? What remains of subjectivity when it is split in two?

By confronting these questions with precise aesthetics, powerful performances, and a multi-layered plot, the show doesn’t answer everything — but reminds us that the human subject, even fragmented, resists. In every innie who bleeds, who dreams, or who screams, there is a refusal to be just a number. There’s someone inside — and that someone wants to live.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.