Perhaps not everyone made the same association, but women of Generation X had two alter egos on TV screens and cinema, as well as in newspapers and books—on different continents, yet facing the same battles for autonomy, authenticity, and love. On one side, a stylish New Yorker, reflective and somewhat narcissistic, navigated a time when women were taking their first steps—in Manolo Blahnik, of course—toward professional and sexual independence. On the other hand, a chaotic, funny, insecure Londoner, also awkward and not entirely fashionable, constantly fighting with the scales, wasn’t a columnist nor a serial dater, but wanted to be somebody.

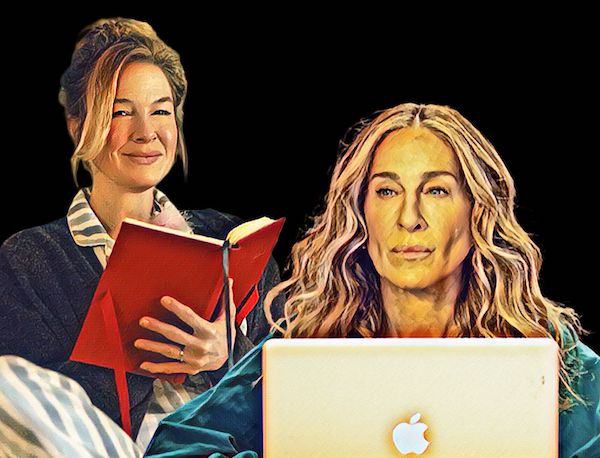

That’s right—the contemporaries Carrie Bradshaw and Bridget Jones have always shared a similar trajectory. Even today, in fact, both have reached their fifties—married to the love of their lives, only to become suddenly widowed and needing to reinvent themselves amid grief and changing times.

Few female figures became as emblematic of the turn of the millennium as they did. Paradoxically, today, they are no longer as aspirational as before, even facing some rejection among their most faithful fans. Why is that? After all, they still represent the dilemmas of the modern woman.

Just to recap: both were born from newspaper columns written by women and migrated to other media with spectacular success—Bridget to books and film, Carrie to television, then movies, and now a new series. Their stories intersect in the contemporary female imagination: they’re mirrors of desires, fears, and contradictions experienced by generations of women who crossed the end of the 20th century and entered the 21st with freedom, but also solitude, aesthetic pressure, and emotional doubts.

The Beginning: Columns That Became Phenomena

The pioneer was not Carrie Bradshaw, but Bridget Jones, who first appeared in 1995 in the humorous columns by Helen Fielding for The Independent. Those quickly turned into the novel Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996), an absolute hit that redefined the chick lit genre by combining references to Pride and Prejudice, contemporary neuroses, and a comic self‑deprecating tone.

Carrie was born from Candace Bushnell’s New York Observer chronicles, published as a book in 1996 and adapted by HBO into the series Sex and the City in 1998. The character, played by Sarah Jessica Parker, became an icon of the urban, sexually autonomous woman—a sort of New York alter ego for the same anxieties experienced by Bridget on the other side of the Atlantic.

If Carrie quickly gained a face and a voice, Bridget only made it to the movies two years after the second book, portrayed by an American actress who nailed a perfect British accent. Renée Zellweger, however, won over the skeptics and created a Bridget who resonates across generations, earning an Oscar nomination for her performance.

The Chaotic Pioneer

Before her, Toni Collette declined the invitation, and actresses such as Helena Bonham Carter, Cate Blanchett, Emily Watson, and Rachel Weisz were considered, as well as Cameron Diaz and Kate Winslet.

Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996 – book / 2001 – film) introduces 32‑year‑old Bridget: single, working at a publishing house, smoking too much, drinking too much, trying to lose weight, and fretting over being single while pressured by friends and her mother. Amid hilarious mishaps and comments about underwear, she becomes involved with her lothario boss, Daniel Cleaver (Hugh Grant), and grows close to Mark Darcy (Colin Firth), a reserved and upright lawyer—in a plot directly inspired by Pride and Prejudice.

Next came Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (1999 – book / 2004 – film), where Bridget tries to maintain a relationship with Mark Darcy while grappling with her own jealousy, insecurities, and Daniel’s persistent presence. The plot turns more chaotic with a Thai prison escape and other absurd confusions, but all wrapped in charm. Although the tone of the second film is more farcical, the character still resonates as a symbol of human imperfection.

Here, cinema and literature diverged. In 2013, Mad About the Boy was published—a darker book in which Bridget is widowed, caring for two children, navigating grief, motherhood, and dating apps at fifty. Mark Darcy died on a humanitarian mission, and Bridget tries to be “cool,” dealing with Twitter, younger men, and her own wrinkles. Though divisive, the novel was praised for its honesty.

In 2016, Bridget Jones’s Baby (based on Fielding’s 2005 columns in The Independent) omitted the earlier book’s events. Bridget is single at 43, thriving in her career, but discovers she’s pregnant without knowing whether the father is Mark Darcy or the nice billionaire Jack (Patrick Dempsey). The tone is lighter, but it sensitively addresses the pressures of late motherhood and new family dynamics.

The Mad About the Boy film, released in 2023, was sweeter and less sombre than the book, but like And Just Like That, it lost the spark that once made us excited about Bridget—we miss Mark Darcy as much as she does. Still, the Bridget we know is there, which allows the story to balance nostalgia with emotion. Carrie should have a chat with her.

The Irresistible Neurotic Superficiality of Carrie

Carrie was the alter ego of journalist Candace Bushnell. Arriving on premium cable in 1998, the show ran for six seasons. We witnessed Carrie Bradshaw and her friends—Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha—exploring sex, love, careers, and friendship in New York. Carrie, a newspaper columnist, narrated the series and experienced ups and downs with various men—but especially with Mr. Big, the enigmatic executive with whom she had an on‑again, off‑again relationship for years. The series was revolutionary for giving voice to four independent, sexually active, financially free women—with all the complexities and contradictions that entail.

The first film, in 2008, was a direct continuation: Carrie was finally going to marry Big, but he left her at the altar. After rebuilding her self‑esteem with the help of friends, she re‑evaluates her feelings and ultimately marries Big in an intimate, simple ceremony. The film was commercially successful, though criticized for feeling like an extended episode.

Two years later came the misstep: a second film widely panned as frivolous and culturally insensitive, showing the friends traveling to Abu Dhabi while Carrie begins to question the stability of her marriage. The negative reception marked the saga’s end—at least for a while.

Until 2021, when And Just Like That premiered. Carrie, now in her fifties, sees her life upended when Big dies suddenly. She starts over: coping with grief, dating again, launching a podcast, and facing new social codes—gender‑neutral language, inclusion topics, and new friendships. The other protagonists also navigate contemporary dilemmas. Carrie, widowed, is more introspective, less ironic, and still searching for meaning.

Restarting: A New Arc Shared by Bridget and Carrie

The sadness of Bridget’s new phase was surprising. But it makes sense—challenge her to move forward since she now has two children to raise. Her spirit remains intact, even in her positivity in trying to overcome grief. She feels outdated in the digital world, just like Carrie—an unusual portrait of a middle‑aged woman with intact libido, vulnerabilities, and a sense of humor. Despite loss and aging, Bridget never abandons her uproarious humanity.

In the Bridget Jones’s Baby film—lighter than the book—we see Bridget more mature, self-assured, prioritizing her career as a producer and embracing solo motherhood. In the end, she welcomes the future without idealizing the past. She’s no longer trying to be chosen; she chooses. It makes sense.

Carrie, meanwhile, experiences a tougher arc. And Just Like That portrays a woman unexpectedly quiet, disoriented, and profoundly lonely after Big’s death. It’s a less glamorous, more raw journey: she relearns being single, dating, writing—and becoming vulnerable anew. The series attempts to stay relevant by exploring contemporary themes, but at times veers into didacticism and emotional flatness.

Carrie enters and exits relationships, eventually rekindling with Aidan (another ex‑flame), but she realizes that maybe the past won’t return—and that she must build a new present, with new affections, rhythms, and silences. The tone is less romantic, more existential.

Where Bridget Jones invites us to laugh at our flaws, Carrie Bradshaw tries to provoke introspection about them. One stumbles and laughs; the other still hasn’t decided how to react. Both, however, remain legitimate versions of the modern woman: multiple, restless, self‑analytical, and, deep down, profoundly lonely.

Legacy: What Remains After the Glamour

Almost three decades later, Bridget and Carrie continue to spark discussions—not about “being single at thirty,” but about how to start over at fifty. Few narratives center on the mature woman in a comedic or lightly reflective tone, and that’s where both remain relevant. Not because they represent ideal models, but because they reveal real contradictions.

If Carrie seems like an editorial fantasy of New York and Bridget a comic portrait of suburban London, both are, essentially, metaphors for our desire to love without losing our sense of self. Those who once wanted “to have it all” now just want a good night’s sleep and to wake up with some peace.

Perhaps the greatest transformation of these characters wasn’t changing city, job, or partner—but surviving the passage of time. Carrie and Bridget aged before our eyes: they left newspaper columns for our hearts, and haven’t left since—even when their new storylines seemed out of sync with what we expected of them.

Even if they evoke less idolization than discomfort today, they remain essential for a simple reason: they’re among the few fictions that don’t hide what happens to women after 40, 50, 60. The end of love, the search for meaning, the fear of being forgotten, the unexpected joy of a new beginning—all of that still exists, but rarely with the prominence, grace, and honesty that Bridget Jones and Carrie Bradshaw granted us.

Through highs and lows, their legacy endures. Because perhaps what moved us— and continues to move us—wasn’t the glamour or romance, but the courage to be ridiculous, complex, and honest in the face of the world. And of ourselves.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.