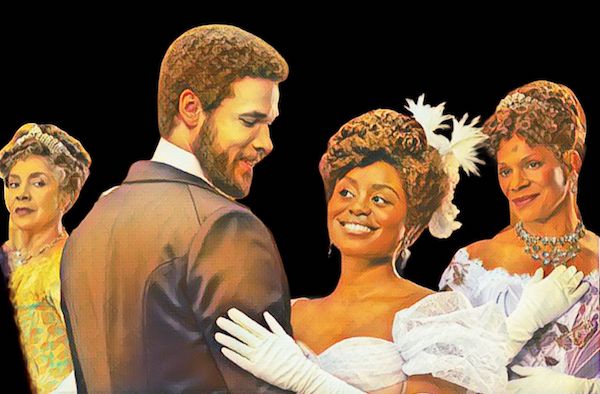

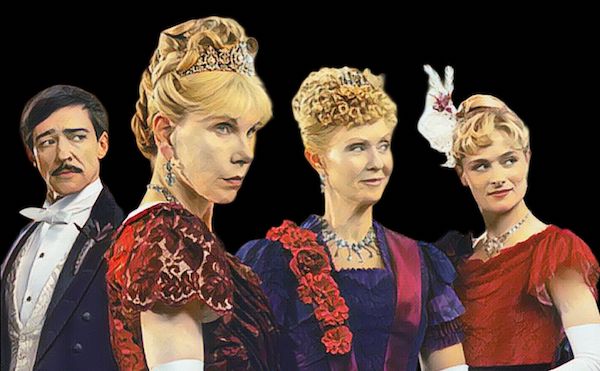

Only three Sundays left, and we’ll return to the past for just eight weeks. That’s right — on June 29, The Gilded Age returns to HBO Max, although it’s uncertain whether this will be the final season. If you’re able to travel and visit New York, you have the chance to explore some of the locations mentioned in the series.

Many of the scenes are filmed in studios or outside the city, but there is still much to see, as few cities in the world preserve the vivid remnants of extreme wealth and deep inequality from the so-called Gilded Age like New York does. Between the 1870s and 1900, the personal empires of figures like Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan emerged — men who shaped the economic, cultural, and architectural landscape of the United States. Their mansions, designed to rival European palaces, still fascinate today with their beauty, opulence, and symbolic power.

This guide presents the main Gilded Age residences you can visit in New York, contextualizing their history and legacy, with tour suggestions and behind-the-scenes curiosities.

The Frick Collection

Curiously, neither Henry Clay Frick nor Andrew Carnegie were portrayed in The Gilded Age, though they would undoubtedly have crossed paths with George Russell. Still, they serve as inspiration for the character.

Frick’s house is one of the hidden gems for those who love visiting New York. The museum’s collection is beautiful, but what always takes my breath away is the house itself. Henry Clay Frick was a steel tycoon and banker associated with Andrew Carnegie — and perhaps one of the most feared men of his time. Involved in controversial episodes such as the Homestead Massacre, Frick embodied the ruthless “self-made man” of the Gilded Age. But he was also a patron of the arts with a sharp eye. When he commissioned his Fifth Avenue mansion (designed by Thomas Hastings), he was already planning for it to become a museum after his death.

Frick lived there only a few years, from 1914 until 1919, but the space was preserved exactly as he intended: silent halls, walls lined with tapestries and paintings, all framed by the European refinement he so admired. The museum underwent a long renovation and reopened in 2024, with its original collection reinstalled in the historic rooms. It’s an intimate, almost reverent experience.

Website: frick.org

The Morgan Library & Museum

J.P. Morgan wasn’t just a legendary banker — he was also an obsessive collector. His library began as an annex to his home but grew to become an institution of its own. Designed by Charles McKim (of the famed McKim, Mead & White trio), the Morgan Library is a jewel of Italian Renaissance revival, with walnut paneling, hand-painted ceilings, and the aura of a secular cathedral.

Morgan collected rare books, illuminated manuscripts, letters from kings and scientists, and scores autographed by Beethoven and Mozart. After his death, his son transformed the library into a public institution — a move reflecting, in part, the pressure these magnates faced to “legitimize” their wealth through cultural philanthropy. Today, the museum offers sophisticated temporary exhibitions and guided tours of the home’s historic spaces.

Website: themorgan.org

The Vanderbilt Mansion

Located in Hyde Park, outside Manhattan, Frederick Vanderbilt’s palace is pure Beaux-Arts: symmetry, monumental columns, and marble- and silk-lined salons. With more than 130 rooms surrounded by terraced gardens and an impressive view of the Hudson River, it may be the most accessible of the Vanderbilt homes to understand the scale of the family’s dreams (and vanity).

Part of the National Park Service. Offers guided tours of the house and gardens.

nps.gov/vama

Roosevelt House

In the heart of the Upper East Side, this mansion was a gift from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s mother when he married Eleanor. It was here that the first ideas of public policy were born, which would eventually lead him to the presidency and shape the U.S. during the New Deal. Today, the space belongs to Hunter College and houses a public policy institute. A reminder that not all Gilded Age legacies were aesthetic — some ideas here changed the 20th century.

Tours by appointment.

roosevelthouse.hunter.cuny.edu

Payne Whitney Mansion

Perhaps the most discreet of the grand Fifth Avenue houses, it now houses the cultural services of the French Embassy. The interior details still impress: marble columns, carved furniture, bronze grilles. The house has survived as a symbol of a time when wealth was displayed with a near-baroque theatricality.

Partial access. Hosts Albertine Books and cultural events of the French Embassy.

albertine.com

Neue Galerie

Built in 1914 for William Starr Miller, an industrial magnate, the house that now holds one of Manhattan’s most interesting galleries was designed by Carrère & Hastings (the same architects behind the Frick Collection and the New York Public Library). This Beaux-Arts building was restored by Ronald Lauder to house the Neue Galerie, dedicated to German and Austrian art. In addition to Gustav Klimt’s iconic “Adele Bloch-Bauer I”, the museum offers a visual and historical immersion into an aesthetic parallel to the Gilded Age: turn-of-the-century Vienna.

Website: neuegalerie.org

Dakota Building

The Dakota Building is one of the most iconic architectural landmarks of New York’s Gilded Age. Inaugurated in 1884, it was built by Edward Clark, partner of Isaac Singer (of the famed Singer sewing machine), who used part of his industrial fortune to invest in luxury real estate.

At the time, the idea of living in apartments was considered unfashionable by New York’s elite — aristocrats preferred mansions. But the Dakota broke this mold. Conceived as a high-end residential building, it offered the comfort of a single-family home in vertical form: soaring ceilings, hardwood floors, parlors with carved fireplaces, and large windows overlooking Central Park.

The style is German Renaissance with Gothic elements, a choice that evoked solidity, tradition, and distinction — and, in a way, also mocked the chaotic modernity taking over the city.

In the 1880s, the area around the Dakota was still relatively remote and underdeveloped — hence the theory that the name “Dakota” was chosen as a nod to the then-distant Dakota Territory (before it became North and South Dakota). This only underscores the boldness of the project: anticipating the city’s growth and installing luxury where there was once only mud.

Decades later, the building became even more famous for being home to celebrities like Lauren Bacall, Leonard Bernstein, and, of course, John Lennon, who was murdered in front of the building in 1980. The Dakota is also known for its aura of mystery — it inspired Rosemary’s Baby (1968), whose exterior was filmed there.

Today, the Dakota remains one of Manhattan’s most exclusive residences. More than that: it’s a time capsule, preserving the atmosphere, spirit, and aesthetic of an era when New York’s elite began to explore new ways to flaunt — and protect — their wealth. It is not open for visits, but it’s worth admiring from the outside.

New York Botanical Garden

Among the living monuments of New York’s Gilded Age is the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx. Founded in 1891, at the tail end of the Gilded Age, the garden was conceived as a space for science, leisure, and cultural prestige, inspired by London’s Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. The NYBG’s creation was made possible by donations from wealthy families of the era, such as the Lorillards (tobacco magnates) and the Belmonts, who saw support for botany as a refined form of philanthropy and a symbol of status. The Haupt Conservatory, a Victorian-style iron-and-glass greenhouse, was designed by Lord & Burnham — the same firm behind structures in the Palm House, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and Kew itself, establishing a transatlantic link between elite gardens.

In the series, it served as the setting for Marian Brooks’s awkward marriage proposal.

The garden spans 250 acres and features native forests, medicinal plant collections, a Japanese garden, a botanical library, and rotating exhibitions. The landscape was designed by Calvert Vaux, the same architect as Central Park. Visiting the NYBG is like entering a green time capsule, where the ambitions of the Gilded Age manifest not in marble and gold, but in orchids, oaks, and winding trails.

Website: https://www.nybg.org/visit/admission/

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Founded in 1870 with generous donations from families like the Morgans, Fricks, Astors, and others, the Met is a true cathedral of culture. Its current location across from Central Park was built in 1880 and has since been expanded, retaining its Beaux-Arts facade as a signature. It is one of the largest museums in the world and can (and should) be visited — including during evening tours.

Website: metmuseum.org

New York Public Library

The NYPL was officially founded in 1895, during the transition between the end of the Gilded Age and the start of the 20th century, from the merger of three existing libraries:

• Astor Library (founded in 1849 by John Jacob Astor)

• Lenox Library (created in 1870 by James Lenox)

• Tilden Trust (established from the estate of Samuel J. Tilden)

These three men were typical products of the Gilded Age: magnates, collectors, and philanthropists who saw culture as a form of moral affirmation and social prestige.

Construction of the main branch on Fifth Avenue began in 1897 and took over a decade — it was inaugurated in 1911. It represents the final grand expression of the Gilded Age spirit, already propelled by the new century’s progressive momentum.

The building is a Beaux-Arts landmark, with Corinthian columns, monumental staircases, and the famous lion statues “Patience” and “Fortitude.” The interior is even more impressive: crystal chandeliers, painted ceilings, fine woods, and the iconic Rose Main Reading Room, over 90 meters long.

Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall is a quintessential monument of the Gilded Age — both in New York’s cultural history and in the biography of Andrew Carnegie, one of the period’s most emblematic magnates.

Inaugurated in 1891, Carnegie Hall was envisioned and funded by Andrew Carnegie, the steel tycoon who became the era’s greatest philanthropist. Construction began in 1890 and was completed in just one year, designed by architect William Burnet Tuthill and supervised by Carnegie’s wife, Louise, who encouraged him to dedicate part of his fortune to culture and education.

The hall was conceived as a temple of classical music and quickly became one of the most prestigious stages in the world, hosting great names from the start, including Tchaikovsky, who conducted the opening, and later Mahler, Horowitz, Maria Callas, and The Beatles.

The original building — with red bricks and Italian Renaissance details — embodied the Gilded Age spirit at its most noble: the desire to eternalize wealth through art. The main auditorium, the Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage, is renowned for its legendary acoustics. In the upper floors, rehearsal rooms and music education spaces were later added, in keeping with Carnegie’s belief in social mobility through merit.

Alongside the Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum, Carnegie Hall forms a symbolic triangle representing how Gilded Age titans sought to cleanse their fortunes through grand gestures of patronage. But unlike many fleeting luxury monuments of the time, the Hall remains alive, vibrant, and in constant use, true to its original purpose: making art both accessible and monumental.

You can still attend concerts, take guided tours, and explore the behind-the-scenes of this cultural icon.

Website: https://www.carnegiehall.org/Visit

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.