In 1925, Virginia Woolf published a novel whose plot might seem minimal: a woman prepares for a party. A hundred years later, Mrs. Dalloway remains one of the most revolutionary and emotionally penetrating works of modern literature. On the centenary of its publication, the book’s relevance not only endures but has grown, resonating in an age where introspection has become second nature. As George Monaghan recently wrote in The New Statesman, “we are all Mrs. Dalloway now”—not just because we’ve adopted stream-of-consciousness as a narrative style, but because, like Clarissa, we are haunted by fragments of the past, desire, grief, and fear in a present that feels increasingly unstable.

The story of Mrs. Dalloway unfolds over a single day in London in June 1923. Clarissa Dalloway, an upper-class woman, walks through the city buying flowers for her evening party. Along the way, she’s overwhelmed by memories of her youth, of a romance with Peter Walsh, of her intimate friendship with Sally Seton, and of the choices that led her to a safe but emotionally uncertain life. In parallel, we follow Septimus Warren Smith, a young World War I veteran suffering from severe trauma, wandering the streets of London on the brink of collapse, hearing voices and experiencing poetic and terrifying visions. Their connection is symbolic: Septimus represents the death that shadows Clarissa, the pain she senses and skirts, the fragility she feels even though society insists on masking it.

Woolf wrote Mrs. Dalloway after two nervous breakdowns and a suicide attempt. The creation of the novel coincided with a moment of artistic confidence, but also intense vulnerability. As she recorded in her diary, she wanted to write about “life and death, sanity and madness” side by side, separated only by a door—just like Clarissa and Septimus. She believed literature should reveal not the exterior of things, as the Edwardian writers she criticized had done, but “the soul, the spirit, what happens within”—like a tunneling process that breaks through appearances.

In this sense, the novel became an exploration of psychological time. Clarissa Dalloway reflects on what she has lost: her love for Sally, the possibility of a more authentic life, and her youth. She is not a tragic heroine in the classical sense, but her melancholy is constant. Septimus, more than any other character in modernist fiction, embodies the human wreckage of war and medical failure. He sees the world with extreme sensitivity, but is unable to live in it. His death—by—jumping out of a window—is a fierce critique of contemporary psychiatry and a denunciation of the chasm between inner suffering and public treatment.

Clarissa, upon hearing of the death of a stranger, has a sudden, almost mystical sense that this death somehow belongs to her. “She felt glad that he had done it; thrown it away,” she thinks, in one of the novel’s most haunting and lyrical passages. Woolf never wrote of suicide as an ideal, but she understood the death drive as something that hovers even in moments of joy, even in brightly lit ballrooms.

The aesthetic and emotional power of Mrs. Dalloway has reverberated for generations, and its influence expanded through other equally powerful works. In 1998, Michael Cunningham published The Hours, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel that intertwines three stories: that of Virginia Woolf writing Mrs. Dalloway in 1923; that of Laura Brown, a 1950s housewife reading the novel as she contemplates suicide; and that of Clarissa Vaughan, a contemporary woman in New York caring for a friend with AIDS while preparing a party in his honor. The novel was adapted into a film in 2002, starring Nicole Kidman (in an Oscar-winning performance), Julianne Moore, and Meryl Streep. The Hours is not just a homage to Woolf but a modern translation of her obsessions: time, loss, language, and the sensation of not fully living.

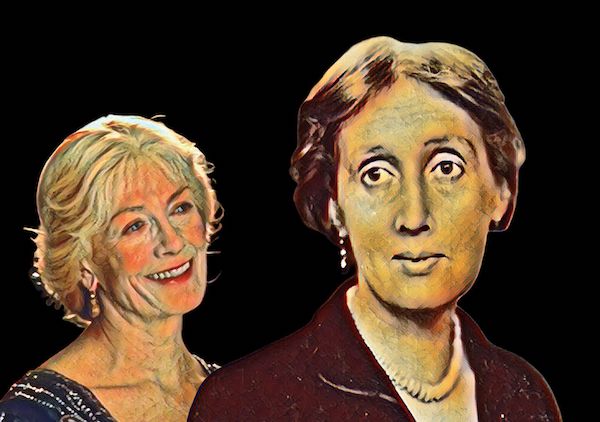

Mrs. Dalloway itself was adapted for the screen in 1997, with Vanessa Redgrave in the title role. The film preserves the elegance of Woolf’s prose and delicately captures the silences, glances, and temporal shifts that mark the original text. Redgrave portrays Clarissa with moving ambiguity—a woman who lives in society but feels the weight of absence like no one else.

What makes Mrs. Dalloway eternal is not just its formal beauty or historical importance. It’s the way Woolf captured, with almost clinical precision, the fissures of the modern psyche. She wrote at a time when quantum physics was beginning to show that nothing is fixed, and her literature shares that instability. As Monaghan notes, the introspective project Woolf inaugurated may have also been a trap: the more we look inward, the more we fragment. Modernity promised we’d find light by digging through darkness—but perhaps, as Clarissa realizes at the end of the novel, the mystical center of the soul “evades” us, and intimacy often ends in solitude.

A hundred years later, Mrs. Dalloway remains a powerful reminder that we all have “cracks—and that’s how the light gets in,” as the saying goes. But also that those cracks can shatter us. Clarissa survives, dances, and smiles at her party. But Septimus’s silence—the abyss between them—lingers as an echo. Woolf didn’t give us a solution, but an emotional map. An invitation to listen to what the city doesn’t say. To catch the thoughts before they form into speech. To live, even when afraid. Because, in the end, “this is life—a moment, a June day—London—and everything is lit.”

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.