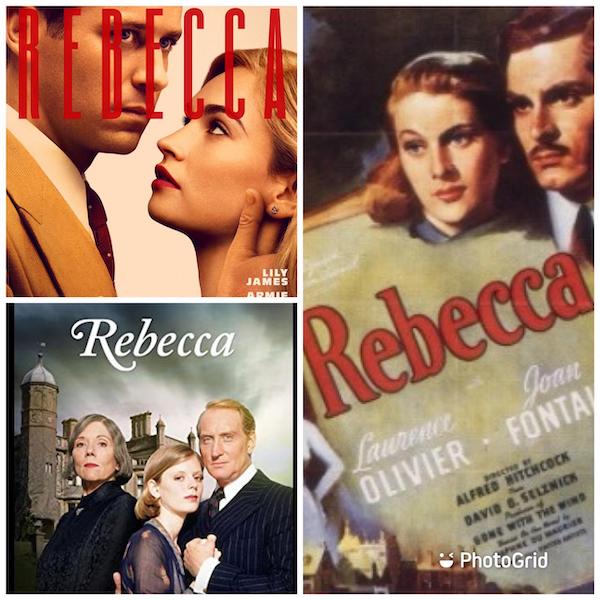

In 2020, Netflix released a remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic Rebecca, starring Lily James in the role once played by Joan Fontaine and Armie Hammer stepping into Laurence Olivier’s shoes. It wasn’t a hit, and it reminded me of the long-standing controversy surrounding the novel before it became a film. Indeed, Rebecca is one of the most scandalous cases of alleged plagiarism in literary history—a possible copy of a Brazilian bestseller. So what exactly is unforgettable about this whole story?

In 1934, a psychological novel made waves in Brazil

In 1934, Brazilian author Carolina Nabuco published A Sucessora (The Successor), a psychological novel that follows the drama of a modest young woman, Marina, who marries an older and wealthy man, Roberto Steen, and moves into a mansion haunted by the ghostly presence of his deceased first wife, Alice. The plot centers on Marina’s discomfort as she is constantly compared to the former lady of the house, whose memory lingers in portraits, personal objects, and especially through Juliana, the loyal housekeeper. The novel builds a growing tension between the young protagonist, suffocated by her new social role, and the echoes of a woman who still dominates the domestic space from beyond the grave.

Following its success, just four years later in 1938, British author Daphne du Maurier published Rebecca, an international bestseller with a strikingly similar premise. The narrator—whose name is never revealed—is also a lower-class young woman who marries a wealthy widower, Maxim de Winter, and moves to the Manderley estate in Cornwall. There, she is tormented by the memory of Maxim’s first wife, Rebecca, whose shadow dominates the corridors, staff, and even the husband’s heart. The housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, is the main keeper of Rebecca’s memory and seeks to make the new wife feel inadequate. The gothic, atmospheric narrative deepens into mystery and suspense, culminating in a dramatic revelation about Rebecca’s death.

The similarities between the two books are numerous. Both center on an insecure young woman, displaced in an aristocratic environment, living under the oppressive shadow of a dead woman who still emotionally dominates the house and those around her. Both Marina and Rebecca‘s narrators are emotionally immature, vulnerable to manipulation, and constantly compared to the previous wife—more beautiful, elegant, and sophisticated. In both novels, the housekeeper plays a crucial role: Juliana and Mrs. Danvers are fiercely loyal to the deceased, resentful of the new wife, and act as guardians of the house’s “institutional memory.” The stifling atmosphere of the mansions—whether the Brazilian one, with its portraits and silences, or the English one, shrouded in mist and memory—serves as a metaphor for the protagonists’ psychological imprisonment.

Despite these notable convergences, there are important differences. A Sucessora (The Successor) takes a more psychological and social approach, exploring the codes of Brazil’s 1930s elite, with a focus on gender roles and family conflicts. Rebecca, on the other hand, adopts the tone of a gothic suspense novel, with elements of mystery and crime. Nabuco’s narrative is in the third person, creating some distance between the protagonist and the reader; du Maurier chooses a first-person point of view, giving the story more emotional immersion. The endings also differ: while Marina in A Sucessora undergoes a process of self-assertion amidst veiled conspiracy and erasure, Rebecca climaxes with the revelation that Maxim killed his former wife—and the ultimate destruction of Manderley suggests a tragic catharsis.

The plagiarism accusation emerged soon after the international success of Rebecca. Carolina Nabuco claimed in her memoirs that she had sent a translated version of A Sucessora (The Successor) to American and British publishers—including the same literary agency that would later represent du Maurier. When the similarities became evident, The New York Times Book Review published a 1941 review highlighting the parallels and questioning Rebecca‘s originality. Nabuco later revealed that, when Hitchcock’s adaptation premiered in Brazil, United Artists tried to get her to sign a statement affirming that the similarities between the books were mere coincidences. She refused.

Daphne du Maurier denied any prior knowledge of Nabuco’s work and responded to The New York Times with a letter defending her novel as a product of imagination, noting she had been accused by other “obscure” authors of stealing ideas. It’s worth noting that Rebecca also shares thematic similarities with Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, reinforcing the idea that certain female archetypes—the erased woman, the previous wife, the house as a symbol of the unconscious—are recurrent in Western literature.

The case was never taken to court. Carolina Nabuco chose not to sue du Maurier. Critics and readers remain divided: for some, it’s a clear case of plot appropriation; for others, the similarities are superficial and may be due to coincidence or literary conventions. To this day, the controversy lives on, particularly among scholars of Brazilian literature who see in A Sucessora not only a forgotten precursor but also an example of the historical invisibility of female voices from the Global South in the international literary canon.

The debate around the alleged plagiarism between Rebecca and A Sucessora (The Successor) was never legally resolved, but it’s far from mere gossip. It’s a documented and serious dispute that raises questions about authorship, cultural colonialism, and the boundaries of originality in literature. Even if intentional plagiarism is never proven, the fact that Carolina Nabuco wrote a story so close to du Maurier’s four years earlier remains an undeniable literary fact.

An enduring classic through Hitchcock’s lens

It must have been painful for Nabuco when du Maurier‘s Rebecca became “one of the most remarkable novels of the 20th century”—both for its popular impact and cultural legacy across books, film, theater, and television.

Published in 1938 by Victor Gollancz, Rebecca quickly became a bestseller in the UK and US. It spent over a year on The New York Times bestseller list, reaching millions. Contemporary critics were divided: while many praised it as a “modern gothic romance” or “masterful psychological mystery,” others dismissed it as “women’s literature”—a biased label typical of the era, which didn’t stop the book from becoming a long-lasting hit.

The opening line—“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again”—is now one of the most iconic in English-language literature. The dark atmosphere, psychological tension, and the absent yet omnipresent figure of Rebecca turned the novel into a powerful study of jealousy, identity, guilt, and class.

Already known for previous novels (Jamaica Inn, The Loving Spirit), Daphne du Maurier was catapulted to literary celebrity, though she also faced pressure from fame and ongoing comparisons to authors like Charlotte Brontë, with many critics dubbing Rebecca a “modern Jane Eyre.”

Hitchcock’s 1940 film: international acclaim

The book’s success was cemented by its stage adaptation and then the 1940 film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, produced by David O. Selznick. Starring Laurence Olivier as Maxim de Winter, Joan Fontaine as the unnamed narrator, and Judith Anderson as the unforgettable Mrs. Danvers, the film was a triumph.

It won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1941—Hitchcock’s only film to do so. It also won Best Cinematography and received nine additional nominations, including Best Director. The screenplay was altered slightly (due to the Hays Code, Maxim could not be a murderer), but preserved the eerie tone and the focus on the nameless protagonist. Judith Anderson’s performance as Mrs. Danvers left a lasting impression.

This adaptation brought the book to an even wider audience, ensuring its cultural endurance. Beyond Hitchcock’s version, Rebecca was adapted for radio (with Orson Welles), television, theater, and even opera. As mentioned, the most recent version came in 2020, starring Lily James, Armie Hammer, and Kristin Scott Thomas, met with mixed reviews and lacked the classic’s impact.

Over the decades, Rebecca influenced countless authors, screenwriters, and filmmakers. Its narrative—centered on the fear of replacement and the haunting memory of another woman—can be traced through works ranging from Jane Eyre to Gone Girl, The Wife, Gaslight, and other stories exploring female psychological destabilization.

In recent years, the novel has been widely reinterpreted through the lenses of gender, identity, and trauma. Many feminist readings see Rebecca as a study in male control, symbolic female rivalry, and the repression of unconventional sexuality—with Mrs. Danvers often read through a queer lens.

The book is also praised for its masterful use of absence: Rebecca never appears in the flesh, yet dominates everything. The narrator—nameless and undefined—represents the erased woman, struggling to occupy a space never meant for her.

Thus, Rebecca was not just a publishing success—it became a cultural phenomenon that transcended decades and borders. Its gripping narrative, complex characters, and haunting atmosphere have secured its place in both literary and cinematic canons. Still reprinted, translated, studied, and reimagined today, Rebecca‘s shadow lingers—not as a threat, but as proof of the lasting power of a great story.

The original version and Rio’s society

A Sucessora (The Successor)’s narrative follows Marina’s growing anxiety as she faces the ghost of Alice, who seems to subtly and disturbingly haunt her new life. Marina feels like a “successora” destined to fail—both in her marriage to Roberto and in the mysterious world shaped by his former wife.

Carolina Nabuco’s style is introspective, emotionally nuanced, and explores themes like female insecurity and the struggle for identity within a marriage shaped by social expectations. It also tackles the pressure on women to conform to idealized standards and how the past haunts the present—especially through constant comparison with Alice. The mansion becomes a near-claustrophobic space, symbolizing the protagonist’s psychological entrapment.

Published in 1934, A Sucessora (The Successor) belongs to Brazilian modernism, though with a less experimental tone than some contemporaries. It was a major success in Brazil and gained popularity through its television adaptation.

The 1978 telenovela was produced by TV Globo, written by Manoel Carlos, with Susana Vieira as Marina, Rubens de Falco as Roberto, and Nathalia Timberg as Juliana. Oddly, though it was successful and inspired remakes across Latin America (in Colombia, Argentina, and Peru), Globo never re-adapted it.

A Sucessora transcends the genre of romance, diving deep into emotional complexity, exposing the anguish of identity formation amid the shadows of the past and the stifling expectations of patriarchal society. A classic of Brazilian literature that engages with universal themes of suffering, self-assertion, and inner liberation. Isn’t it time for a revisit? Just a thought…

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.