Of all the true stories set during the Gilded Age, spoilers and leaks for this Sunday’s episode confirm that we’ll hear a direct mention of the scandalous Madame X, one of the most iconic paintings of the late 19th century, by John Singer Sargent.

The era’s greatest portraitist, Sargent, will be commissioned by Bertha Russell to immortalize Gladys in a painting—a moment glimpsed in both the trailer and official photos from the season premiere. In conversation with the American painter, Bertha will mention Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, the millionaire who became forever known as “Madame X” in one of art history’s most delicious scandals.

Julian Fellowes has been delighting us with these kinds of references, and it’s worth digging deeper into this one. After all, few people know that one of Europe’s greatest art scandals was actually born… in New Orleans. And no, that’s not an exaggeration. The protagonist of this story was born right there, in hot and charming Louisiana, and ended up immortalized in one of the most famous works at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Origins of the Mysterious Madame X

Amélie was born in 1859 in a house that still stands on Toulouse Street, in the heart of the French Quarter. The daughter of a French Creole mother and a Confederate major, she lost her father as a child—he died at the Battle of Shiloh—and soon after lost her sister to yellow fever. Her mother, seeking a new beginning, moved them to Paris, where the family already owned an apartment. That’s where Amélie grew up, well-educated and determined to climb the highest rungs of Parisian society.

The strategy worked—up to a point. She married young to French banker Pierre Gautreau, gaining both status and freedom. With no mother to watch over her, Amélie flourished. She was considered one of the most beautiful women in Paris, though her looks didn’t match the classical French ideal. Her distinction? Extremely pale skin, which she enhanced with lavender powder and even small doses of arsenic (!). She dyed her hair with henna, wore tightly fitted dresses, and never shied away from attention. Rumors of her extramarital affairs fueled gossip columns, and many men—and artists—became obsessed with her.

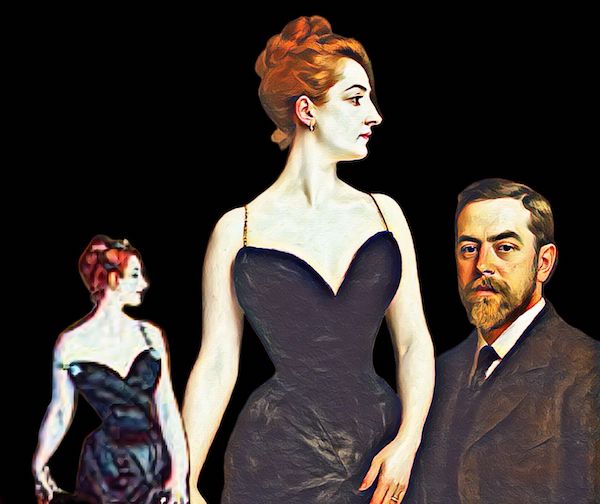

One of those artists was John Singer Sargent, a young American painter also trying to make a name for himself in Paris. When the opportunity to paint Amélie arose, he seized it: he offered to paint her for free. She agreed. The portrait required over 30 sittings in 1883, and the dress—a black gown with delicate straps—was chosen by Sargent himself. He wanted something elegant, sensual, but mysterious. In the original version, one strap had fallen off her shoulder, subtly but provocatively.

And that’s exactly what set Paris on fire.

The 1884 Scandal That Shook the Art World

When the portrait was unveiled at the prestigious Salon of 1884—the most important art exhibition in France—the reaction was instant and vicious. It didn’t matter that Amélie was technically clothed. The scandal was in the subtext. The woman in the painting was clearly a lady of high society… but she was depicted like a courtesan: bold, alluring, self-assured. What shocked the French wasn’t nudity—it was the fusion of desire and respectability. A woman could be desirable or respectable, but never both.

Critics were merciless. Some said her skin resembled a corpse. Others mocked her pose and called the palette hideous. The newspaper L’Événement noted that the painting might seem promising from a distance, but up close, it was sheer ugliness. Sargent was ridiculed by the press. Amélie became a caricature in satirical magazines like Le Charivari. Even her own mother begged the artist to withdraw the painting. In desperation, Sargent repainted the fallen strap back into place—but it was too late.

The damage, however, was already done. Amélie withdrew from public life and never regained the same social allure. She sat for other portraits later, but none caused a stir. She aged far from the spotlight. Sargent, humiliated, left Paris and tried his luck in London and then New York, where his career would take off again (and that’s where The Gilded Age comes in). Later in life, he would go on to paint figures like Theodore Roosevelt and Rockefeller. Yet he always considered the portrait of Madame X his greatest work. In 1916, he sold the painting to the Metropolitan Museum for a thousand dollars. A year earlier, Amélie had died. “I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done,” he said at the time. And it was. The world just wasn’t ready to see it yet.

Today, the painting is one of the Met’s most iconic works. It continues to inspire artists, fashion designers, musicians, and writers—like an American Mona Lisa, with a Southern origin and a French soul. At first glance, modern viewers might not understand the scandal. But take a moment longer, and you’ll see something unsettling: the tension between what is expected of a woman and what she chooses to be.

Madame X is more than a portrait. It’s a timeless provocation. And it all began with a girl of ghostly white skin, born in sultry, vibrant New Orleans.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.