Before it hit movie screens and became a phenomenon in 1975, Jaws was a book—and before that, it was a very real nightmare. That’s right: to write Jaws (published in 1974), Peter Benchley drew inspiration from TWO real-life events and turned them into a story that might have remained buried in the pages—if not for the brilliance of Steven Spielberg.

The novel Jaws tells the story of a massive great white shark that attacks swimmers in a fictional coastal town called Amity, prompting the local police chief, an ichthyologist, and a shark hunter to join forces to kill it.

The truth, however, was far more tragic. While the initial spark for the novel came from a real 1964 event, when a fisherman caught a massive great white shark weighing over two tons off the coast of Montauk, New York, it was a series of shark attacks in 1916 along the New Jersey shoreline that proved far more terrifying. Benchley combined both stories to create Jaws—but we’ll take the reverse path and look back at the facts.

The 1916 New Jersey Attacks: The Summer of Fear

Between July 1 and July 12, 1916, a series of shark attacks shook the New Jersey coast. In total, five people were attacked, and four died—an extremely high number for shark incidents, which were then considered exceedingly rare, nearly impossible, in American waters. The case caused widespread panic and was heavily reported in the press.

The first victim, 25-year-old Charles Vansant, was killed by a shark while swimming near the beach at Beach Haven. A few days later, 27-year-old Charles Bruder was attacked while swimming at Spring Lake and had his legs torn off. He died during the rescue attempt.

The following week, three more people were attacked on the same day while swimming in Matawan Creek, a brackish river nearly 11 miles from the ocean—a place where no one imagined a shark could be. Eleven-year-old Lester Stillwell was killed; 24-year-old Stanley Fisher tried to rescue him and was fatally injured; and 14-year-old Joseph Dunn was attacked shortly afterward but survived with injuries.

Can you imagine the public shock? Today, it would cause a media frenzy. But 109 years ago, it was even more intense. Authorities closed beaches, armed patrols were organized, and a nationwide shark hunt began.

Scientists were baffled by the idea of a shark swimming so far upstream. Many believe the culprit was either a great white shark or a bull shark—the latter known for venturing into rivers and brackish waters.

This case was one of the first to spark mass fear of sharks in the U.S., helping solidify the terror Benchley would later exploit in Jaws.

Frank Mundus and the 1964 Shark: The Hunter Who Became a Legend

As if the 1916 saga weren’t enough material for books and movies, in 1964—ten years before the novel—fisherman Frank Mundus made international headlines when he captured a giant great white shark.

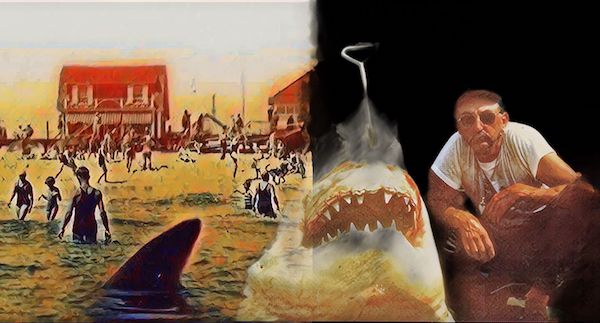

Fishing off Montauk, Long Island (New York), Mundus reeled in a shark estimated at over 2 tons. The shark was harpooned, winched aboard, and its carcass displayed on the beach. The image of this colossal predator, hung like a trophy, was widely circulated in the media and deeply impressed the public imagination.

What helped was that Frank Mundus was a charismatic and eccentric figure, known for his flamboyant outfits and for organizing “shark safaris.” Long before the modern environmental awareness movement, he would take tourists and thrill-seekers out to hunt large sharks.

Peter Benchley, a journalist and writer for publications like National Geographic and Newsweek, had a long-standing personal fascination with marine life and was captivated by Mundus. He used the story of the massive shark as the foundation for imagining what could happen if such a creature became a constant threat to a coastal community—just like in 1916. Mundus became the direct inspiration for the character of Quint, the brash, tough-talking shark hunter in Jaws.

Interestingly, years later, Mundus would also become an advocate for shark conservation, acknowledging that his actions had helped perpetuate a negative image of the animals.

Changes in the Film

Although Steven Spielberg’s film version retained the book’s core structure, there were some major changes. The novel, for instance, includes subplots involving adultery (Chief Brody’s wife has an affair with oceanographer Matt Hooper) and more overt political tensions around the closing of the beaches. Spielberg chose to eliminate or downplay these elements to focus on suspense and action, which ultimately contributed to the film’s universal success.

Ironically, both Peter Benchley and Frank Mundus later regretted the portrayal of sharks in Jaws, realizing they had helped fuel a monstrous and inaccurate image of the species. In the years that followed, Benchley became a vocal advocate for marine conservation and shark protection, even stating he wouldn’t have written the book had he known more about the true behavior of sharks.

Thus, Jaws was born from the fusion of real events, ocean myths, collective fears, and a touch of journalistic imagination. The result was a work of fiction that forever changed the public’s relationship with the sea—and, thanks to Spielberg’s adaptation, launched the blockbuster era in cinema.

I’d say the 1916 attacks might just resurface in the collective imagination… don’t you think?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.