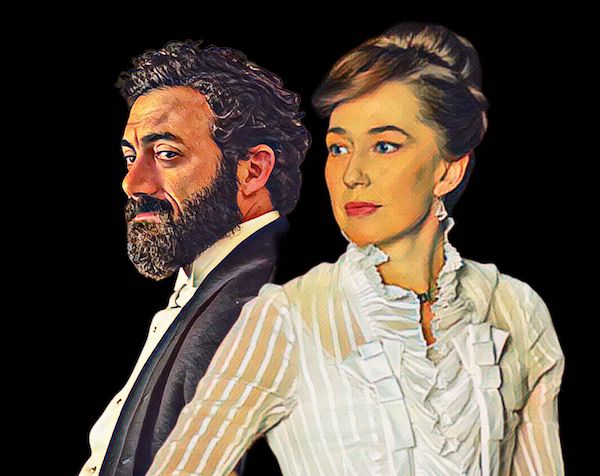

George and Bertha Russell are perhaps the most fascinating and morally ambiguous couple in The Gilded Age. They cannot be labeled as villains, nor as heroes. They are relentless protagonists, master strategists willing to do whatever it takes to maintain the position they forcibly conquered at the top of New York society. Unlike the aristocrats of “old money,” the Russells inherited nothing: they built their empire railroad by railroad, ball by ball, scandal by scandal — and that is part of their allure. While many admire them, few fully trust them, and even fewer can predict their next move.

George, inspired by the real-life tycoon Jay Gould, is a hard-nosed industrialist, though not always cruel when it comes to his children. His love for Bertha is evident and perhaps the only genuine emotional anchor his character possesses. But that love does not stop him from acting with cold precision in the business world, where he manipulates, threatens, and buys silence with the same ease he signs contracts. Let us remember that a man took his own life after crossing George’s vengeful practicality — and far from shedding a tear, George merely shrugged off the tragedy.

Bertha, portrayed with icy precision by Carrie Coon, is the embodiment of a woman’s social ascent in an era that imposed strict limitations based on birth. The daughter of Irish immigrants — a background that still haunts her behind the scenes — she crafted her public persona with determination, luxury, and cunning. Her ambition isn’t vanity; it’s existential. Bertha knows that, in the America of the Gilded Age, a woman like her is only respected if she is feared.

The third season promises to delve deeper into this tension between facade and origin, with the arrival of Bertha’s sister — a figure who threatens to reopen the wounds she tried to bury beneath diamonds and French tapestries. The mere presence of a relative who carries the same social memory Bertha rejected is set to shake her armor and perhaps force her to confront what she had to give up to rise. In this sense, her past is not just a shadow — it is a political and emotional time bomb.

At the same time, Bertha and George’s marriage — seemingly solid — shows signs of deep cracks. The dispute over their children, especially Gladys, has already revealed diverging views on what it means to “protect” someone. For George, protection means granting freedom within reasonable limits. For Bertha, it means controlling every aspect of someone’s life to avoid any risk. While George is willing to do whatever it takes to expand his fortune and political influence, Bertha focuses on securing powerful friendships and advantageous marriages for their children — particularly Gladys.

This interference is the central point that transforms Bertha into a “villain” in the eyes of some and places her not only in opposition to her children but also to her husband, who, oddly enough, wants them to marry well — but also for love.

Another key difference became even more evident with the arrival of Enid Winterton, an unexpected and formidable adversary. A former employee who climbed the social ladder with the same ferocity as Bertha, Enid not only challenged her rival in the social arena but dared to flirt with George, creating a vortex of emotional insecurity Bertha is not accustomed to feeling. For the first time, she was confronted with the possibility of not being the most strategic woman in the room.

George, for his part, did not yield to Enid’s advances — but neither did he denounce them. His omission carried the weight of betrayal — not physical, but symbolic — and it redefined the dynamics of trust between them. The press has already speculated that the couple may split, not due to a lack of love, but because of diverging principles. There is a latent tension between them, a growing distance that the writers are likely to explore even more now that Bertha finds herself cornered by both external and internal forces.

Another looming point of conflict is the budding romance between Larry Russell and Marian Brook. Although the series has yet to confirm whether Larry’s parents will formally oppose the match, it’s hard to imagine Bertha — who views relationships as political alliances — welcoming a young woman without a dowry, lineage, or status. Marian represents everything Bertha rejected to get ahead in life: idealism, fragility, and sentimentality. George may sympathize more with Marian, seeing in her a sense of honesty and dignity that reminds him of older values. But his loyalty to Bertha will be tested — especially if she insists on sabotaging her son’s romance. The tension between a father who wants his son to be happy and a mother who demands a strategic marriage may once again expose the fractures within the Russell marriage.

This potential clash unfolds within a broader context of instability. Bertha is under siege: her rival Enid has not backed down, her daughter threatens to defy the imposed path, her origins resurface with the arrival of her sister, and her marriage teeters under the weight of unspoken truths. At the center of this storm, she tries to maintain her posture, her perfect gown, her precise words. But how long can a facade hold when the foundation begins to crack?

In its third season, The Gilded Age will not offer viewers a fairy tale of social ascent. Instead, it promises to unmask the internal contradictions of a couple who reached the top by being smarter, faster, and colder than everyone else. George and Bertha Russell are neither heroes nor villains. They are survivors. And it is precisely this gray area that makes them so compelling. They do not act out of kindness, but out of convenience. They do not trust — they tolerate. They do not yield — they calculate. And when they do yield, it’s for a reason that serves them — not always the noblest one.

If the third season continues on this path, we will witness either the implosion of a facade or the reinvention of an even more powerful alliance. We will see a Bertha forced to confront her past, a George pressured to choose between status and sentiment, and two children trying to escape the transactional logic that governs their family. The Russells’ marriage, their fortune, their public image, and their legacy are all at stake. The game is high. And no one plays it better than they do. But, like every Gilded Age, perhaps this one too is about to reveal its cracks beneath the polished surface.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

2 comentários Adicione o seu