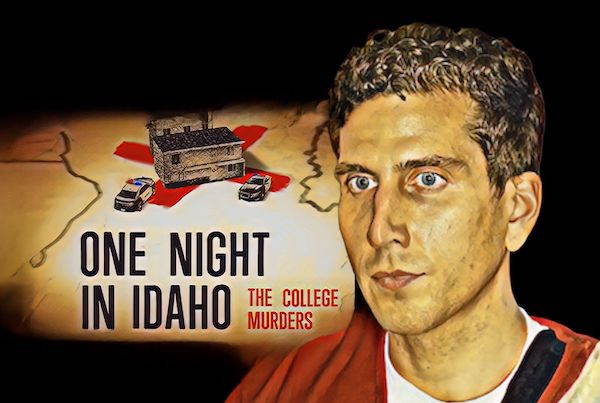

The murder of four university students in Idaho in November 2022 still causes shock, disbelief, and a never-ending series of unanswered questions. With the trial of the suspect, Bryan Kohberger, scheduled for August 2025 — nearly three years after the crime — the feeling is that the truth is becoming increasingly blurred, not only because of the passage of time but also because the case has turned into a rare media phenomenon, one that embeds itself in popular imagination and seems to resist clarification. A macabre and apparently senseless story, which gained additional layers with the recent revival of the topic by the Dateline program and the Amazon documentary One Night in Idaho: The College Murders, directed by Liz Garbus, set to premiere in July.

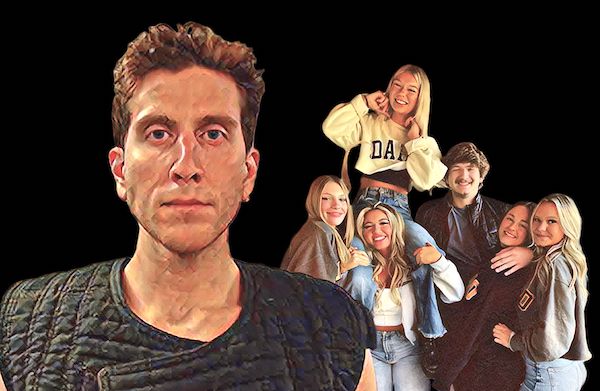

By now, the basic chronology of events is known: in the early hours of November 13, 2022, four young people — Kaylee Goncalves, Madison Mogen, Xana Kernodle, and Ethan Chapin — were brutally stabbed to death in a shared house near the University of Idaho. Two others were in the house and survived. One of them even claims to have seen the masked killer. The case, initially local, quickly gained national attention, and the arrest of Kohberger, a criminology PhD student at Washington State University, around New Year’s, brought both relief and unease. After all, who was he? What was his motivation? Why did he enter that house? How did he choose the victims — and perhaps more disturbingly, why did he leave two of them alive?

None of this has been clarified so far. The prosecution maintains that Kohberger committed the crime and has in hand a set of evidence it considers compelling: his DNA on the knife sheath, phone, and location records, surveillance footage of a white Hyundai, internet searches for murder methods, and profiles of serial killers. The defense, on the other hand, claims he is innocent, did not know any of the victims, and that the evidence presented is circumstantial, contestable, and insufficient for conviction. It hints at another suspect. It insists that the press has compromised the impartiality of the process.

What there actually is is a fog. A brutal crime, apparently committed without an emotional connection between the victim and the attacker. An accused who denies guilt and does not confess. A surviving witness who saw the man’s face but could not prevent the tragedy. And a whole country that, even before any trial, has already formed its convictions. Between documentaries, podcasts, forums, TikTok, and Reddit theories, what we have is a “true crime” culture that consumes every detail as entertainment and turns those involved into characters. Kohberger became an obsessed figure, fascinated by serial killers. The victims, reduced to smiling portraits and interrupted promises. The witness, at times a martyr, at others a dubious figure.

The judge issued a “gag order,” forbidding the defense and prosecution from speaking outside the court. The intention was to avoid leaks, protect the right to a fair trial, and shield the jury from collective hysteria. But it is impossible to contain the Dateline effect. It is impossible to divert attention from the imminent Amazon premiere. It is impossible to ignore that, by 2025, the public will have watched two full seasons of investigative content on the case while the official criminal process has yet to begin.

Delaying the trial was an attempt to cool the commotion. But in practice, it only allowed the commotion to spread. We face a modern dilemma: how to fairly judge a crime already immortalized in pop culture, with narratives contested by journalists, writers, influencers, and amateur detectives? How to guarantee justice when the very notion of a “fair trial” seems incompatible with the dynamics of the internet?

The case inevitably recalls In Cold Blood, Truman Capote’s classic, both because of the bucolic setting and the seemingly gratuitous nature of the violence. But there are fundamental differences. In the 1959 Clutter family murder, almost a year passed shrouded in total mystery until the killers were found, along with motive, confession, and a relatively quick resolution. Capote investigated the case after it was already closed. In Idaho, we are watching everything unfold in real time, with cameras already rolling and copyrights negotiated before the first hearing.

What makes the Idaho crime so disturbing is not only its brutality but its persistent mystery. The absence of answers. The banality of evil is embodied in a suspect who, to this day, has not explained his role. The tension between the desire to understand and the desire to consume tragedy as spectacle. Dateline offers more pieces of the puzzle, but no solutions. Amazon promises to humanize the victims, but also anticipates a script that should belong in the courtroom.

This kind of media exposure is already beginning to alter the essence of criminal justice. In a system that depends on impartial jurors, what can be done when citizens called to serve have already learned every detail of the case? Already watched all the interviews with family members, followed the theories, and felt moved by the dramatic reenactments? When collective memory is shaped by YouTube clips, emotionally charged trailers, and viral threads on X (formerly Twitter), what remains of technical judgment?

Courts try to respond with what they have: changing jurisdictions, juror anonymity, silence orders, and careful selection. But the truth is that classical legal tools are no match for the speed of information. What we live today is a cruel paradox: while demanding transparency and attention for victims, the excess of information threatens the very integrity of the verdict.

It is necessary to rethink the limits between information and influence. The risk is that the courtroom becomes merely the final stage of a play already publicly performed, where the defendant enters condemned or acquitted before even speaking. More serious still, the victims cease to be seen as real people and become archetypes of innocence or martyrs of a commercial script. Or that the public begins to confuse justice with narrative — and verdict with fan service.

There is no easy solution. Delaying trials may not solve the problem. Banning reports is also unfeasible in democracies. Perhaps it is time to discuss creating temporary informational silence zones around certain trials — a difficult concept to implement, but one worth debating. Another possibility would be to strengthen juror training, including psychological support and media filters before the trial, something that today seems impractical but may become indispensable.

Because more than ever, the risk is not only condemning innocents or acquitting the guilty but losing trust in the system itself. If verdicts come to be seen as products of collective hysteria or well-orchestrated narrative campaigns, what remains of justice? Ultimately, the Idaho case is not just about who killed four young people. It is a test to see whether we are still capable of judging calmly in times of information overload. And if we fail, perhaps the crime Kohberger or another committed will not be the only irreparable one.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.