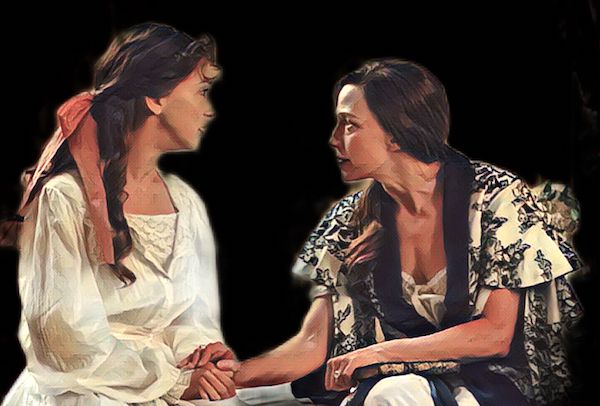

The third season of The Gilded Age seems determined to follow the real-life storyline that inspired it—right up until the moment it decides not to. Bertha and Gladys Russell, portrayed with pinpoint precision by Carrie Coon and Tassia Farmiga, form one of the most fascinating duos on the show: a mother obsessed with social ascent and a daughter pressured to obey. So far, their trajectory echoes clearly that of Alva Vanderbilt and her daughter Consuelo—among the most notorious cases of maternal coercion in 19th-century New York elite. But beware of the spoiler Tassia Farmiga let slip in an interview: in Episode 6 this season, something changes. Bertha gives in. Gladys wins. And we wonder: will it last? Or is it just another move in Bertha Russell’s chess game?

The historical precedent: Alva and Consuelo

Alva Vanderbilt was one of the most ambitious figures of her generation. When she realized New York’s old money looked down on the newly wealthy Vanderbilts, she orchestrated a spectacular ball—anyone left off the guest list effectively made it the event of the year (Season 1 of The Gilded Age). Later, she took on the opera crowd (Season 2), but the series avoided one crucial plotline. In real life, Alva and William divorced—a scandal that cost Alva much of the status she had fought for. To recover, she made another bold move: orchestrating her daughter’s marriage to forcefully reclaim her social standing.

Consuelo, then 18, was compelled to marry the Duke of Marlborough in a ceremony that sealed the Vanderbilts’ entry into European nobility. She did not want the marriage. She was in love with another man. She cried at the altar. But Alva’s pressure was relentless—and public.

Decades later, Consuelo revealed the trauma she endured in her autobiography. Alva, by then involved in the women’s suffrage movement, made a late confession: “I never should have forced that marriage.” Mother and daughter reconciled—but only after irreparable damage had been done.

Carrie Coon partially defends Alva’s strategy through Bertha Russell’s logic in the series. “This is her only job. This is her only outlet to use her intellectual skills, her ambition. Bertha isn’t allowed in the business sphere. She says this to George. She could have been a senator or CEO, but she is relegated to this sphere [raising children]. So her job is to marry off her children well, so they can take the next step. She is teaching them to have more power and influence than her. She’s very ambitious for them—because it’s all she is allowed to do,” Coon explains.

Bertha and Gladys: mirrors and distortions

The Gilded Age doesn’t hide its inspiration from real events. Bertha Russell, from the first season, is a force of nature, determined to push her family to the top of the social ladder, no matter the cost. Gladys, meanwhile, is the rich young debutante whose main value lies in her marital prospects. The tension between them builds each season. Bertha withholds suitors, manipulates balls, and isolates her daughter. And Gladys, so far, resists ineffectively.

Worse, she counts on her father’s help, yet may be disappointed. “George sees what’s happening, but he doesn’t ask the right questions,” said Morgan Spektor. “Bertha can cite logical and moral arguments against George’s position. And, probably to be fair, George didn’t think much and decided he wanted his daughter to marry for love, but he didn’t consider the kind of arguments that Bertha brought to the table.”

But Episode 6 of Season 3 introduces a significant crack in that mirror. Bertha, for the first time, doesn’t choose what’s best for her daughter—but what makes her happy. It’s a small yet radical gesture. It’s the first time the show gives us reason to speculate that this story may not repeat Consuelo’s tragic path. Could that really happen?

“I think she (Gladys) resents her mother for much of the season, but by the end, Bertha actually helps her achieve, in the present moment, happiness,” Tassia Farmiga revealed in an interview.

Redemption—or strategy?

The big question is: has Bertha changed, or has she merely delayed her win? Carrie Coon, in her masterful performance, never gives away her character’s true feelings. Bertha could simply be yielding temporarily, making a concession to earn Gladys’ trust before delivering the final blow. Or she might genuinely be discovering that her love for Gladys outweighs her need to win the social “game.”

Tassia Farmiga, in earlier interviews, hinted that Gladys is starting to understand the limits of her own freedom. Her rebellion is still naïve, rehearsed, and easily absorbed by a long-term strategist mother. What seems like a victory may actually be another trap: after all, as she says herself, Gladys is privileged, naive, wants to live for love and happiness, but doesn’t yet understand how the world works. That’s the opposite of her mother, who came from nothing and built everything.

“There’s not much Gladys can do. She’s in a position where society, her parents, and friends have many expectations. Everyone comes to her and says, ‘You must do this; it’s the right thing.’ And she feels lost,” the actress commented. “There’s very little you can do when you’re up against Bertha and George Russell. They’re both very ambitious people, and they create the pathway forward—and the rules and the rights. And I think Gladys gets swept along and just has to go with it,” she continued.

The turning point

What’s most revealing comes next: “I think she resents her mother for much of the season, but by the end, she gains her freedom, thanks to Bertha. Bertha comes and shows her how to manipulate the situations she’s in to make Gladys happier for the first time, genuinely, in the present moment. Bertha is always thinking of a happy future, and in Episode 6, Bertha and Gladys have a connection. Bertha truly helps her achieve, in the present moment, happiness.”

Wow. What comes next?

What The Gilded Age can do differently

If Julian Fellowes and Sonja Warfield choose to follow historical precedent, the arc is already set: Gladys will be forced into a marriage she doesn’t want, suffer in silence, and perhaps decades later achieve some symbolic repair. But if the series really wants to break with the past—and with audience expectations—there is room for a bolder twist.

This moment of mutual understanding between mother and daughter could mark the start of a new dynamic. Gladys could claim the agency Consuelo never had. Bertha could discover that maternal love is not weakness, but another kind of power. Or, conversely, this seeming reconciliation could be a false calm before the final storm—a way to set the stage for the ultimate blow, whether through a forced marriage or a more devastating emotional betrayal.

What sets The Gilded Age apart from mere historical dramatization is its freedom to deviate. And perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the current season is this tension: viewers know what happened to Alva and Consuelo, but they don’t know if Bertha and Gladys will repeat the same script.

A mother who loves too much

Bertha Russell is not just her daughter’s antagonist—she’s also her distorted mirror. Gladys yearns for freedom but doesn’t yet grasp its price. Bertha knows the cost—and may, on some level, want to spare her. It’s possible that, unlike Alva, Bertha realizes the mistake before making it. But it’s equally possible that Bertha’s love remains—for as Harry Richardson says about Larry—“a love that survives restrictions.” And maybe that love includes restricting her own daughter.

Gladys, in turn, must grow enough to face her mother as an equal. Her desire for autonomy still sounds naive—and the series could use this conflict to show not only a young woman’s emancipation, but also the real difficulty of being free in a society that educates its daughters to please.

The pivotal moment

Whatever path the show takes, Episode 6 plants a seed of rupture. For the first time, we glimpse the possibility that Gladys will not be just a reenacted Consuelo—but a new woman with the right to choose. And Bertha, by yielding, reveals that her heart may be as strategic as her ambition.

If The Gilded Age wants to go beyond historical recreation, this is the moment. The mirror is cracked. Now we wait to see whether it will shatter—or reflect something entirely new.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.