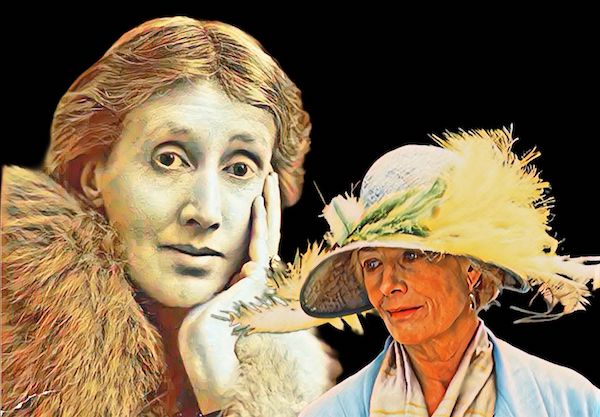

In 1924, while working on Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf wrote one of the most sensitive and insightful readings of Jane Austen, focusing especially on Persuasion, the last novel Austen completed before her death. Published posthumously in 1817, Persuasion marks a tonal shift in Austen’s oeuvre: more melancholic, more introspective, and more interested in what remains unsaid than in what is narrated directly. Woolf grasped this with clarity and recognized in that shift a glimpse of what Austen might have become had she lived longer.

What Woolf didn’t state explicitly—but which emerges with quiet force—is that Mrs. Dalloway, the novel she was then shaping, resonates intimately with this more mature, subdued, and emotionally vulnerable Austen. The affinities between Persuasion and Mrs. Dalloway aren’t about direct influence, but about shared emotional ground, thematic convergence, and a parallel exploration of female interiority.

Both novels unfold largely within the theme of regret, in which the protagonists revisit crucial memories and silently confront choices that have defined their lives. In Persuasion, Anne Elliot, now 27, is unexpectedly reunited with Captain Wentworth, the man she once loved and was persuaded to give up. In Mrs. Dalloway, Clarissa Dalloway, as she prepares for an evening party, revisits her past affections—especially with Peter Walsh and Sally Seton—while grappling with time. Both women are marked by age, reflection, and a quiet reckoning with loss and possibility.

More than their plots, what connects these two novels is their tonal intimacy and the way their authors construct female consciousness through silence. In her review, Woolf praises Austen’s ability to depict “not only what people say, but what they leave unsaid.” That observation could just as easily describe Clarissa Dalloway, whose entire presence is shaped by what remains unspoken—her repressed desires, her private doubts, and her unacknowledged wounds.

Both protagonists are shaped by time—its weight, its missed chances, its quiet erosion. Anne Elliot is a woman who has aged in the shadows, excluded from action but rich in emotional insight. Clarissa Dalloway, though more publicly visible, also feels herself aging, sensing the tension between past and present. Their experiences are infused with memory, and both struggle to interpret the value of what was lost and what still might be reclaimed.

Empathy is another deep link. Anne Elliot’s perceptiveness toward others—especially those who have wronged her—is strikingly compassionate. Clarissa, in her turn, feels an intense, unspoken connection to Septimus Smith, the shell-shocked veteran. Their link is never overt, yet it suggests an invisible thread of shared vulnerability. This delicate, intuitive sensitivity is precisely what Woolf admired in Austen.

In her essay on Persuasion, Woolf seems to project part of herself into Austen’s trajectory. She imagines Austen, had she lived longer, evolving toward the depth and complexity of a Henry James or even a Proust. Woolf writes that Austen might have developed “a new method, still clear and composed, but deeper and more suggestive, to express not only what people say, but what they leave unsaid; not only what they are, but […] what life is.” This could be a manifesto for Mrs. Dalloway itself—a novel that strives to render human experience not through overt drama but through mood, rhythm, recollection, and silence.

The emotional intertextuality between Persuasion and Mrs. Dalloway is less about citation than about kindred spirit. Woolf recognized in Austen a shared restraint, a refined emotional intelligence, and a trust in the power of what is quiet, elliptical, and subtle. Both authors rejected grandiosity in favor of nuance; both wrote about women negotiating the currents of social expectation and private longing; both believed that what lies beneath a sentence might matter more than the sentence itself.

To read Mrs. Dalloway through the lens of Woolf’s 1924 reflections on Austen is to witness a conversation across generations—a dialogue not only between two literary masters, but between two women committed to honoring the inner lives of women. Woolf’s review is not just literary criticism; it is a gesture of artistic kinship. She does not merely explain Austen—she recognizes her as a possible mirror, a sister in both sensibility and craft.

And perhaps that is why the review becomes something more rare: a form of love.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.