From the Idaho case to the trials of O.J. Simpson, Menendez, and Trump: how the legal gag order collides with the culture of total exposure and collective online investigation.

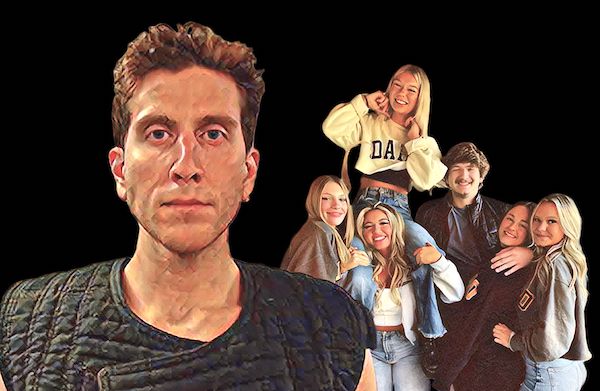

In 2022, four young college students were brutally murdered in an off-campus house near the University of Idaho. The crime, committed during the night, with no visible witnesses, no signs of forced entry, and minimal traces, triggered an instant national uproar. When Bryan Kohberger, a criminology student and teaching assistant, was arrested as the prime suspect, the case entered a parallel dimension to the justice system itself: that of public opinion, shaped in real time by social media, YouTube true crime channels, and forums of “amateur investigators.”

What few knew, however, was that this case would also become one of the most emblematic contemporary examples of the use—and the limits —of the so-called gag order. And that, by officially silencing those involved, institutional silence only amplified the noise outside.

What is a gag order — and what does it say about us?

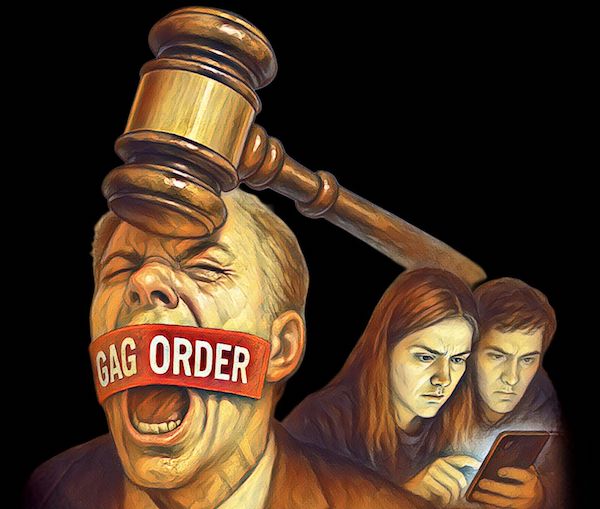

A gag order is a legal tool in the United States that restricts individuals involved in a case from speaking publicly about it. Created to protect the integrity of trials — especially in high-profile cases — it aims to prevent inflammatory statements from contaminating jurors, influencing witnesses, or undermining the due process of law. But while it was originally a shield against the excesses of traditional media, it now faces a much more chaotic and uncontrollable force: virality.

In the age of social media, a gag order doesn’t just stop us from knowing something — it reminds us, with every censored headline and speculative YouTube video, that we’re being denied the truth. And what we’re denied becomes even more desirable. Silence becomes a story.

The origin: how the gag order emerged in American law

The gag order concept stems from the Anglo-Saxon legal system, specifically from British Common Law, but its modern application in the U.S. dates back to the early 20th century, with the rise of mass media. The U.S. Supreme Court began shaping its use with rulings such as Sheppard v. Maxwell (1966), in which sensationalist media coverage was deemed to have compromised the trial of a doctor accused of killing his wife. That case made clear that the State had an obligation to balance freedom of the press with the defendant’s right to a fair and impartial trial.

Since then, American judges have been able to issue specific restraining orders — known as gag orders — to limit media access or prohibit those involved from making public statements during a criminal trial. These orders apply only to those directly tied to the case: attorneys, prosecutors, law enforcement, witnesses, and sometimes the families. They do not extend to the general public or the press — meaning journalists can continue covering the facts based on legally accessible information. Essentially, people “can speak,” but only about very basic facts — often without context. That’s why many argue the effect can be worse, by generating more curiosity and misinformation, which adds many layers to the debate.

The Idaho case and the pact of not knowing

In the Kohberger case, the gag order was extensive: prosecutors, defense attorneys, police, victims’ families, and anyone directly involved were prohibited from making public statements. Simultaneously, the judge sealed nearly all case documents — from search warrants to forensic reports. What was meant to protect the investigation and ensure a fair trial had, in practice, a paradoxical effect: it pushed the case into the backstage of a massive wave of speculative content.

YouTubers with millions of views deciphered crime scene maps, Reddit users analyzed GPS signals and the suspect’s academic connections, and TikTok accounts reenacted theories with suspenseful music. The courtroom’s silence gave way to the internet’s noise. Witnesses were deemed suspects and harassed (like the two students who found the bodies or the surviving roommate who took hours to call the police).

When, just weeks before the trial was to begin in 2025, Kohberger accepted a plea deal to avoid a jury trial by pleading guilty, the expectation that we would finally see the events of that night revealed — the timeline, the motives, the evidence — was shattered. Without a trial, there is no courtroom exposure. And without exposure, what remains is the abyss: not knowing.

A Dateline documentary that influenced the trial

The strict information control imposed by the gag order in the Idaho case was partially breached by the release of a special NBC documentary, The Terrible Night on King Road, aired on Dateline, and the upcoming special arriving on Amazon in July 2025 as part of the series One Night in Idaho: The College Murders.

In the NBC production, journalists had access to confidential evidence — including unreleased surveillance footage, cell tower data suggesting Bryan Kohberger’s presence near the crime scene, and even text messages exchanged with university peers.

The impact was immediate: the defense argued that the leaks compromised the right to a fair trial, violated the gag order, and could negatively influence public opinion and potential jurors. More than that, there were concerns that the premature disclosure of confidential elements could damage the prosecution’s ability to seek the death penalty — a possibility still under consideration at the time. Thus, the documentary, intended to clarify the case for the public, ended up exposing the justice system’s limits in the face of media power: in attempting to fill the institutional silence, it may have altered the legal course of the case.

Justice, spectacle, and the right to watch

In the United States — and to some extent, in all of Western culture — the justice system has become a stage. The 1995 trial of O.J. Simpson, broadcast live, was the modern prototype of this transformation. For months, the entire country followed testimonies, DNA analyses, racial tensions, and defense strategies as if watching a soap opera — and in the end, when O.J. was acquitted, the national polarization mirrored what we now see in any trending topic.

From that point on, other high-profile cases sparked similar reactions: the Menendez brothers, who killed their parents and were tried under the television spotlight; Michael Jackson’s 2005 trial, surrounded by scandal and conspiracy theories; and, more recently, the multiple trials faced by Donald Trump, each with its own gag order, challenging the balance between freedom of speech and institutional security.

In all these cases, the public didn’t just want the verdict. They wanted the process — the clashes, the evidence, the body language. Because ultimately, justice too became a narrative to be consumed.

The gag order and collective anxiety

Why does this affect us so deeply? Because true crime today is not just a genre of entertainment. It’s an emotional response to a world full of insecurity — a way to make sense of evil, to rationalize the irrational, and sometimes, to feel a simulacrum of justice. People watch trials like they watch series: to find meaning, to follow clues, to complete the puzzle.

When a gag order comes into play, it interrupts that narrative logic. It suspends the anticipation, withholds the climax. It’s necessary, yes — but emotionally frustrating. And that reveals something essential about our time: how much we confuse justice with visibility, truth with spectacle, and the right to know with the right to watch.

Internet sleuths and the new public court

The vacuum left by gag orders today is filled by a legion of “internet sleuths” — amateur detectives who scour social media, maps, satellite images, and even school records. On the one hand, they democratize public interest; on the other, they often spread misinformation, make devastating mistakes (including falsely accusing innocent people), and fuel collective anxiety.

In the Idaho case, as mentioned, people close to the victims were harassed online. Baseless theories circulated as fact. In an algorithm-driven age, truth competes with virality — and loses.

What’s at stake: the balance between knowing and judging

The primary function of a gag order is to protect the defendant and the judicial process, but its side effect is unavoidable: it also protects the State from public scrutiny. And in times of digital surveillance and institutional crisis, that raises alarms.

When justice becomes inaccessible, it also becomes suspicious. If the public feels it is being deliberately kept in the dark, it creates its own version of the story. And in polarized societies, those versions become weapons — political, cultural, emotional.

What changes with the Idaho case

In the Idaho Murders, the gag order was especially broad. Beyond silencing the formal parties, it also blocked media access to a range of official documents — including search warrants, forensic reports, and investigation records. This led to legal challenges from major outlets such as The New York Times, CNN, and Associated Press, which accused the judicial system of violating the principle of transparency and the First Amendment right to information.

What sets this case apart is not just the use of the gag order, but its duration and intensity. And now, with Bryan Kohberger’s decision to accept a plea deal and avoid a full trial, the gag order may technically be lifted, but in practice, much of what would have come to light in court will remain unknown. The absence of a trial means the evidence, reports, contradictions, and public statements — all the elements society expects to process and understand a crime — will not surface.

Thus, the gag order, which should have been temporary and protective, becomes a permanent seal of confidentiality. Justice may be done in the legal records — but the public sense of justice remains suspended.

Do gag orders “help” the guilty?

The gag order is not a villain — but it is not neutral either. It is a bitter medicine, administered to preserve a fair trial, but one that today needs to be reassessed in light of the new ways we produce, consume, and share information. The Idaho case exposes this dilemma precisely: by protecting the process, the judicial system denied us answers. And in denying answers, it generated noise — and distrust.

Modern justice finds itself in a paradox: the more it needs to protect silence, the more it is judged by the noise. And in this clash between century-old laws and instant networks, what’s at stake is not just the fate of a defendant — but the very way we understand truth, justice, and narrative in our time.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.