With the massive success of The Gilded Age on HBO Max, not only have fans immersed themselves in the real-life stories that inspired the series, but there has also been a renewed interest in the great literary classics that portray New York’s 19th-century elite — among them, the works of Henry James and, especially, The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton. The current season of the series, by exploring the drama of a possible divorce within high society, speaks directly to the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, which dives into the devastating social consequences faced by a woman who dares to break from her marriage. The timing is perfect: as audiences seek to understand the roots of elegant hypocrisy and the emotional sacrifices that shaped the American aristocracy, Netflix is preparing a new adaptation of the classic — a story that remains as painful as it is relevant.

The Age of Innocence, a novel by Edith Wharton, was published in 1920 during a moment of major cultural transition in the United States — right after World War I, when the values of old American society were beginning to give way to a more pragmatic and less ceremonial modernity. It was in this context that Wharton, already living in France and distant from the New York life she had once known so well, decided to turn her gaze to the past, recreating with precision and irony the aristocracy that had shaped her youth.

Although it was initially conceived as a short novella — a lighter project following the monumental The Custom of the Country (1913) — the book ended up becoming one of the most dense and sophisticated works of her career. The inspiration came from her own experience in the salons of New York’s elite in the 1870s, but also from the realization, decades later, that this society had all but vanished — leaving behind only the memory of its unspoken codes, its hypocrisies, and its emotional sacrifices.

Released to both critical and commercial success, The Age of Innocence won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1921, making Edith Wharton the first woman to receive the honor. The jury praised the novel for its formal elegance, but also for its subtle portrayal of the tension between individual desire and social conventions — something that deeply resonated in a transforming America. Still, some contemporary critics labeled the novel “old-fashioned” for its attachment to the past, failing to see that it was, in fact, a sharp critique of that very past.

“In reality they all lived in a kind of hieroglyphic world, where the real thing was never said or done or even thought, but only represented by a set of arbitrary signs.”

— Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

The novel is set in 1870s New York, portraying a world on the verge of transformation — a world Wharton knew intimately. The so-called Gilded Age was a period of economic growth and the consolidation of old fortunes, but also of moral rigidity and social hypocrisy. Wharton observes this society with a gaze that is both nostalgic and critical, as if writing from the other side of time — she was born in 1862 and grew up within the very elite she depicts.

The novel offers a meticulous portrait of class, exposing the culture, rituals, and anxieties of an aristocracy threatened by modernity and changing social mores. What’s at stake is the preservation of a static order, based on appearances and unspoken rules, where convenience matters more than authenticity.

Newland Archer: the divided protagonist

Newland Archer is introduced as an educated, sensitive, and progressive man — but only within the limits allowed by his class. At the start of the novel, he is engaged to May Welland, the ultimate symbol of purity, predictability, and social correctness. But the arrival of May’s cousin, Countess Ellen Olenska, triggers a profound inner conflict in Newland between desire and duty.

Ellen represents the opposite of May: a woman who challenges convention, marked by the scandal of a failed marriage to a European nobleman. Through her, Newland is forced to see the invisible chains of the society he lives in — and to realize that, though he considers himself free, he is entirely bound by the expectations of others.

The great irony of the novel is that Newland believes he is making independent choices, yet everything in his trajectory shows how deeply he is a product of his time. His arc is tragic not because of lost love itself, but because of his inability to break away from what is socially acceptable.

May Welland: innocence as strategy

May is often interpreted as a passive or colorless character, but a contemporary reading reveals her complexity. She is, in fact, brilliantly effective at protecting her social position and securing the stability she expects from marriage. In one of the novel’s most emblematic moments, May manipulates the situation by announcing her pregnancy to drive Ellen away — showing that, despite her delicate appearance, she fully understands the rules of the game.

The so-called “innocence” of the title can be read in two ways: not only as the supposed purity of May or of New York society, but also as a collective fiction that keeps everyone in their assigned places.

Ellen Olenska: the threat of freedom

Ellen is a figure who both belongs to and stands apart from this world. She carries European sophistication, but also a kind of freedom that is viewed as dangerous. Her presence shakes the social structure because she refuses to follow the pre-written script for a woman of her class.

It’s important to note that even Ellen, despite her strength and independence, ultimately yields to social logic. She retreats, leaves Newland behind, and chooses not to destroy the family structure. Like Newland, she makes a sacrifice — but hers is more conscious.

“I can’t love you unless I give you up.”

— Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

Time as a character

The epilogue of the novel, set 26 years later, is devastating in its melancholy. Newland, now a widower, is in Paris with his son and has the chance to see Ellen again. But at the last moment, he chooses not to go up to her apartment. This final gesture is ambiguous: is it a sign of maturity, resignation, or cowardice? For many readers, it’s the recognition that time has sealed the choices once made — and that the possibilities of another fate died with youth.

This closing passage perfectly completes the cycle, reinforcing the novel’s central theme: renunciation as the foundation of social identity. What defines Newland is not what he lives, but what he chooses not to live.

Style and narrative technique

Wharton writes with surgical precision and refined irony. She is at once empathetic toward her characters and critical of the system that traps them. Her prose is elegant, rich in social and psychological detail, and shaped by a narrative structure in which what is left unsaid carries as much weight as what is spoken.

“The real loneliness is living among all these kind people who only ask one to pretend!”

― Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

The novel employs a third-person narrator that closely follows Newland’s perspective but often views him with ironic distance, revealing contradictions and vulnerabilities he himself does not see.

Why did it take so long to be adapted?

Despite its literary prestige and status as a required text in American universities, The Age of Innocence took over 70 years to receive a major cinematic adaptation. This is partly due to its subtle narrative structure, introspective tone, and lack of dramatic climaxes — all elements that challenge screenwriters and directors. It’s a novel of silences, restrained gestures, and private emotional tragedies — difficult to translate into images without losing its essence.

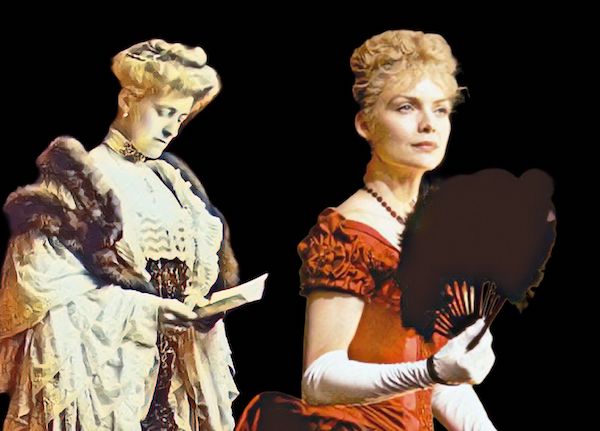

Before the acclaimed 1993 adaptation by Martin Scorsese, The Age of Innocence had already reached the screen in a 1934 RKO production, directed by Philip Moeller. Starring Irene Dunne as Ellen Olenska and John Boles as Newland Archer, the film was based both on Wharton’s novel and on a 1928 stage adaptation by Margaret Ayer Barnes. Just over 80 minutes long, the film aimed for refined aesthetics and elegant performances, but it was a box-office failure and received lukewarm reviews, considered stiff and emotionally flat. Even so, Dunne’s performance drew praise from some critics, and the film remains a curious artifact of how 1930s Hollywood attempted to portray the emotional restraint and sophistication of New York’s high society.

There was also a 1977 BBC television adaptation, made for British TV, starring Irene Worth, Robin Ellis, and Kathleen Beller — a faithful production, though little known outside the UK. It was only with Scorsese — paradoxically a director best known for mafia films and urban violence — that the book received a film treatment worthy of its emotional delicacy.

“Everything may be labelled — but everybody is not.”

— Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

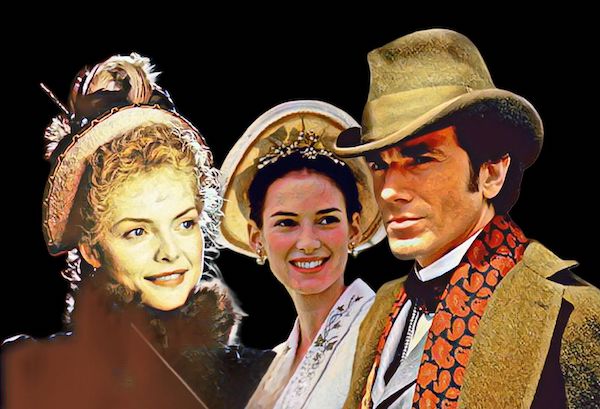

Scorsese stunned audiences with his lush recreation of 19th-century New York society, anchored by restrained performances and precise visual direction. The film was nominated for five Academy Awards and cemented The Age of Innocence as one of the great literary adaptations of modern cinema. The soundtrack by Elmer Bernstein deserves special mention, incorporating Tchaikovsky’s None But the Lonely Heart, Op. 6, No. 6 — the same piece used in the 1934 film.

Now, with Netflix developing its own adaptation, The Age of Innocence is poised to reach a new generation of viewers — perhaps more attuned than ever to the cost of appearances, the violence of politeness, and the dreams buried beneath social expectations.

The pain of conformity

The Age of Innocence is, above all, a meditation on the price of conformity. In a world where what is expected weighs more than what is felt, love is sacrificed in the name of order. Wharton does not condemn her characters, but rather exposes — with painful precision — how even the best-intentioned people can become complicit in a system that imprisons them.

It is a work about what could have been — and about what people don’t dare to do to achieve what they truly want.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.