As published in CLAUDIA

I wasn’t planning to write about The Gilded Age again so soon after my last column — but honestly, it’s irresistible. In these times of re-evaluated girl bosses, it’s striking how ambitious female characters still manage to make people uncomfortable. In The Gilded Age, Bertha Russell might be the most talked-about and polarizing figure — admired for her strength, criticized for her coldness. Watching her feels like witnessing a real-time game of social chess. But what makes Bertha truly fascinating isn’t just her relentless climb to the top of New York’s social pyramid — it’s how she navigates, with surgical precision, the limitations placed on women of her time. And, above all, how she tries to break those chains not only for herself but for her daughter Gladys — even at the cost of the girl’s freedom.

Bertha, played with sharp precision by Carrie Coon, carries an urgency in her eyes that goes far beyond vanity or the desire for recognition: it’s pure survival. Coon has said in interviews that she doesn’t see Bertha as a villain, but as a woman who learned the rules of the game and did what was necessary to ensure her family didn’t just survive — they rose. 2025 is Coon’s year — after her moving, emotional monologue in The White Lotus, where she portrayed a 21st-century woman grappling with the same dilemmas as Bertha in the 19th century, the parallels between the two roles say a lot.

The character is loosely inspired by the real-life figure of Alva Vanderbilt, one of the most influential and controversial women of the Gilded Age, who confronted New York’s elite with rare resolve. Like Bertha, Alva had a daughter — Consuelo Vanderbilt — who became a pawn in her mother’s social ambitions. Consuelo’s arranged marriage to the Duke of Marlborough remains one of the most iconic examples of American wealth marrying into European nobility — and a lasting wound in the mother-daughter relationship.

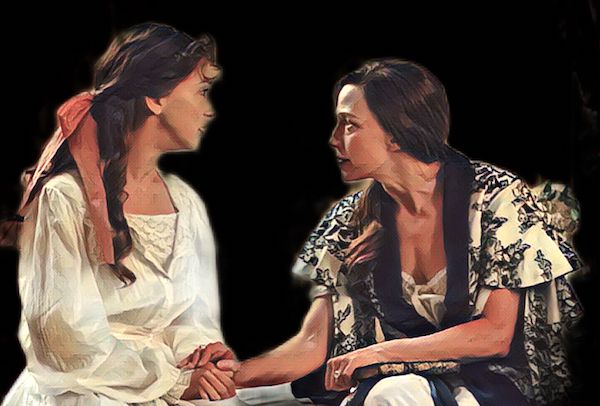

In The Gilded Age, we see this mirrored in Bertha and Gladys’s relationship. The young Gladys, played by Taissa Farmiga, lives under the shadow of a mother who claims to want the best for her — yet routinely silences her wishes. The idea that maternal love can be poisoned by projections, ambitions, and even a kind of generational panic (“I don’t want you to suffer like I did”) is a tension many women recognize. Bertha loves Gladys — of that, there’s no doubt — but she also uses her. The desire to see her daughter “well married” isn’t just a social whim: it’s a long-term strategy, almost military in its precision. Gladys is Bertha’s next move on the chessboard — and perhaps her greatest vulnerability.

In this new season, the tension between the two promises to deepen. Without giving too much away, we’re about to see a more self-aware Gladys, eager to break free from the golden cage her mother built. And Bertha will begin to feel the weight of her choices — maybe even realizing that by projecting her frustrations and dreams onto her daughter, she risks losing the person she loves most.

It’s an old dilemma, but one that never goes out of fashion: where does maternal care end and suffocating control begin? Bertha embodies the archetype of the “architect mother” — a woman who shapes her children’s futures with a firm hand, often without asking what they want. Does that make her unlikable? Perhaps. But it also makes her deeply understandable. In societies that long limited women’s ambitions to motherhood and marriage, many mothers channeled their thirst for power into their children — especially their daughters. In that sense, Bertha’s battle is both deeply feminine and deeply tragic.

The success of The Gilded Age — created by Julian Fellowes, of Downton Abbey fame — lies in part in this complexity. It’s not just about lavish costumes and grand staircases. The series gets it right when it shows how social, class and gender conflicts played out within the home — at dinner tables, in the silences between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law, and in negotiated marriages. If Downton Abbey transported us to the pastoral calm of the English countryside, where tradition still reigned, The Gilded Age dives into a New York in upheaval, where the rules were being written in real-time. And if Downton gave us Cora Levinson — a rich American who marries into British aristocracy — here we witness an earlier moment: when women like Bertha were paving that very path.

Cora, in fact, is a direct descendant of the type of woman Bertha represents. The daughter of an American magnate, raised to enter British high society, she also had a relationship filled with tension and expectation with her own mother — the stylish and commanding Martha Levinson, played by Shirley MacLaine. Their dynamic is more comedic, but it carries the same emotional weight: mothers who live for (and through) their daughters, and daughters who bounce between gratitude and a desperate need for independence.

Perhaps what makes Bertha Russell so unforgettable is this very contradiction: she is fierce, yet wounded. Pragmatic, yet driven by dreams of grandeur. She refuses to accept the closed doors of old-money aristocracy — and yet desperately longs to be accepted by them. Her practicality is her greatest weapon — and her prison. She has no time for romantic illusions or soft ideals of motherhood. Like so many women before and after her, she’s simply trying to survive in a world built by — and for — men. And that alone makes her an unsettling figure, even today.

Bertha Russell doesn’t just want to belong — she wants to dominate. And the price of that may be her daughter’s affection, her husband’s admiration, the public’s sympathy. But as we all know, women who dare too much have never been universally embraced. At its core, The Gilded Age reminds us that behind every embroidered gown and candlelit banquet, there was a silent war being fought. And that mothers and daughters, even when they love each other deeply, don’t always speak the same language.

When in doubt, Bertha speaks the language of power.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.