For the longest time, we — devoted scholars of both fictional and real Gilded Age scandals — were confident: Gladys Russell, Bertha’s ever-watchful daughter who never dares step out of line, was a dramatized version of Consuelo Vanderbilt, the most famous debutante of the late 19th century, forced into a transatlantic marriage with a British duke by her status-hungry mother. A girl traded like a pawn in a diplomatic chess match. A loveless marriage. A bittersweet, belated escape. It all fits.

But… what if we’ve been comparing her to the wrong cousin all along?

Because — plot twist — there was another real-life Vanderbilt named Gladys. Gladys Moore Vanderbilt. Consuelo’s younger cousin, and yet another American heiress who married into European nobility. And this Gladys? She may just be the real blueprint for our TV Gladys — only with far fewer tears and way more staying power.

Born in 1886, Gladys was the youngest daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, the railroad tycoon behind one of America’s largest fortunes. She grew up bouncing between the legendary Vanderbilt mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York and their Newport “cottage,” The Breakers — a house so grand it made Renaissance palazzos look modest. In modern terms, she was the billionaire’s baby daughter, polished to sparkle among dukes and counts.

And this is where the comparison to Gladys Russell starts making more sense: a girl raised under the weight of family legacy, drilled in propriety, but not lacking agency. Unlike Consuelo, whose marriage to the Duke of Marlborough was famously coerced and miserable, Gladys chose her path — or at least seemed to have more say in it. At 21, she married Hungarian Count László Széchenyi, a well-known nobleman from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Their wedding was a full-blown social spectacle: headlines, floral overload, and a gown that would make Lady Whistledown swoon. But there were no reports of tears behind closed doors. Gladys seemed… content. Not that married life was all smooth sailing — László was rumored to be a chronic gambler, and not long after their nuptials, gossip swirled that he had burned through much of her dowry. By 1913, rumors of divorce made their way into the press. Still, Gladys stayed.

And more than that — she turned her title into something useful. When World War I broke out, she didn’t retreat to the safety of her American estates. Instead, she opened up her palace in Budapest to hundreds of reservists and later transformed it into a wartime hospital. For a woman groomed for ballrooms and oil portraits, it was a quietly radical move.

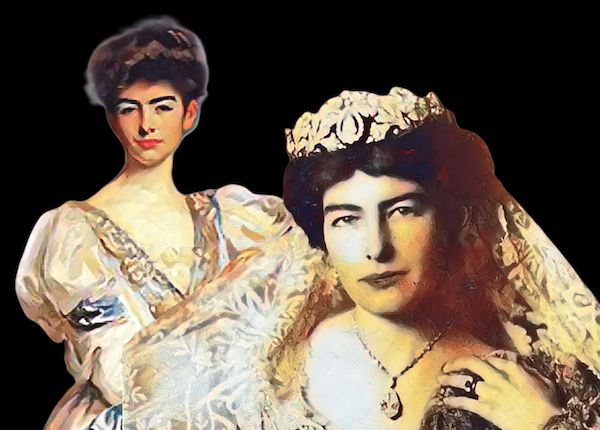

Speaking of portraits — the iconic John Singer Sargent painting of Gladys, done in 1906 when she was just 20, shows her at the height of youth and privilege, captured forever in silk and softness. She looked like the very spirit of the Gilded Age made flesh. And in many ways, she was. But not just as decoration — she was a legacy in motion.

Over the decades, she lived between Hungary and the U.S., raised five daughters (all of whom married into nobility, including a future Earl of Winchilsea), and remained a commanding presence across both continents. She played the long game — not just socially, but historically. When her husband died in 1938, she didn’t crumble or disappear. She simply continued — maintaining her apartment at The Breakers (even after leasing the estate to the Preservation Society for one symbolic dollar), overseeing family matters, and even making cultural contributions.

One of the most iconic? In 1951, she donated her mother’s legendary “Electric Light” dress — yes, the one that lit up with hidden batteries — to the Museum of the City of New York. A brilliant gesture of heritage, ownership, and awareness. She knew that her family was history — and she handed over the proof.

Meanwhile, poor Consuelo was the living portrait of gilded misery. Forced into a ducal marriage by her social-climbing mother, she suffered through years of cold aristocratic duty. Eventually, she escaped and reinvented herself as a progressive and author. Her life was a cautionary tale — noble, yes, but tragic.

But Gladys? She was resilient. Quietly strategic. A Vanderbilt through and through — but one who knew how to bend the rules instead of breaking under them. She didn’t need to rebel to gain ground; she negotiated from within.

If The Gilded Age writers decide to go down this less obvious but far richer narrative route, we may be in for something fascinating. Instead of running from the altar or staging a romantic rebellion, Gladys Russell might just marry for alliance and affection, cross an ocean on her own terms, and wield her family name with subtle power. Not a sacrifice — a strategy.

And let’s be real: that’s a revolution too.

So next time we look at that determined glint in Gladys Russell’s eye, maybe we shouldn’t think of Consuelo’s heartbreak, but of Gladys Vanderbilt’s calculated grace. Less weeping duchess, more diplomatic countess. Less gothic drama, more long game. And perhaps, just perhaps, an ending with more dignity than despair.

Because not all gilded girls go down — some just cross the Atlantic and keep shining.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.