Throughout the three seasons of The Gilded Age, few characters have grown in complexity and subtlety as much as Larry Russell. The son of ruthless railroad tycoon George Russell and ambitious socialite Bertha Russell, Larry seems, from his very first scene, like someone who belongs to a different kind of story. More reserved, refined, artistic, and sensitive than his parents, he serves as a potential bridge between the two worlds that the series constantly puts in conflict: that of new money and that of New York’s old society. But Larry is not merely a mediator — he is also someone in search of his own path, one built through beauty, autonomy, and perhaps, love.

A young man who observes more than he speaks

In the first season, we meet Larry as a recent Harvard graduate, navigating clubs and elite dinner parties, but not yet committed to a specific future. He turns down an active role in his father’s business — a decision George respects, if cautiously. Unlike his sister Gladys, confined by their mother’s will, Larry has the freedom to explore and experience. But that freedom does not mean indifference. Larry is paying attention to everything: his parents’ brutal struggle for social acceptance, the game of alliances, the prejudices of the old elite. And he tries, as much as possible, to maintain a dignified stance — neither arrogant nor servile.

It’s in this context that he grows close to Marian Brook. The two understand each other easily and share a kind of lightness absent from the surrounding social battles. But there’s no real space for romance: Marian is involved with Tom Raikes, and Larry, though clearly captivated, steps back. Still, their conversations reveal a great deal about his worldview. In one memorable moment, when discussing the future, he says he doesn’t want to be just “the son of the richest man in America” — he wants to build beautiful things and leave his own mark. Architecture, then, is not only a profession, but a life project and symbolic escape from the shadow of his parents.

The silent fight for identity

Season two marks the affirmation of that desire. Larry joins an architecture firm, learns to draw, contributes to projects, and starts to be recognized for his own merit. He accepts a commission to restore a theater ceiling — which places him, even reluctantly, in the center of his mother’s battlefield: the opera wars. The gesture is ambiguous. On one hand, it shows he’s still within the family orbit; on the other, it reveals his ability to navigate power circles on his own terms.

It’s also in the second season that Larry becomes involved with Susan Blaine, a socially well-positioned, witty, and ambitious widow. Their relationship becomes a torrid romance, revealing the type of woman he feels comfortable with: not a shy debutante, but someone who, like him, knows the rules and chooses how to play. The affair soon becomes gossip that spreads from Newport to New York, confirming Bertha’s worst fears.

From that point on, his relationship with his mother grows more complex. He respects her, but criticizes her methods. He knows that after his final conversation with Susan, the romance came to an end. So when Bertha insists that Gladys marry a blue-blooded European, Larry firmly opposes it. He believes his sister has the right to choose — and once again, he acts as the humanizing counterweight to his mother’s ambition.

An heir in a different key

Season three deepens this tension between belonging and autonomy. Larry is now regarded as a promising architect, having been invited to projects and consulted on key decisions. He has talent, vision — and a name. But that name, contrary to what traditional society thinks, is not a burden to him. Larry Russell doesn’t want to rid himself of his parents’ legacy — he wants to redefine it.

He doesn’t want to destroy anything. But he also doesn’t want to simply preserve it. His struggle is subtler: he wants to prove it’s possible to be the son of George and Bertha Russell — and still be a decent, creative, free man.

Why is he more accepted?

This partial acceptance that Larry experiences — in opera boxes, elite clubs, luncheons with the Van Rhijn and Astor families — is no accident. Larry studied at Harvard. He speaks the language of the elite. He knows which fork to use, which artists to name, what tone of voice to adopt. He doesn’t pose a threat. And that, for the elite, is crucial.

George and Bertha are seen as invaders. Larry is seen as someone who might always have belonged — or at least, someone who doesn’t need to be pushed out. He is, in practice, what many wealthy young men of the time aspired to be: a new kind of aristocrat, shaped not by blood, but by education and taste.

Relationship with George Russell: pride, conflict, and legacy

The relationship between Larry and his father George is a careful dance between admiration and discomfort. Larry respects his father’s strength and intelligence but disagrees with the utilitarian worldview George represents. George wants his son to “grow up” and take his place in the railroad empire, while Larry, for much of the series, insists on following his own path as an architect.

Season three suggests some alignment: Larry begins to understand the pressure of maintaining a fortune and legacy. George, in turn, seems more tolerant of his son’s artistic inclinations — as long as he stays within the family’s sphere of influence. It’s a relationship of compromise — and tension.

Relationship with Bertha Russell: symbol and instrument

With Bertha, the dynamic is more emotionally delicate. Bertha projects her social ambitions onto Larry. She needs her son to be handsome, eloquent, desirable — the perfect symbol of the Russell name. Bertha opposes the relationship with Susan Blaine, reinforcing her role as a strategic matriarch.

Larry, for his part, admires his mother’s strength but feels invaded by her manipulations. He rarely confronts her directly but carves out spaces of autonomy whenever he can. Bertha wants to mold him; he wants to remain malleable — but unshaped.

Relationship with Gladys Russell: complicity and protection

With his sister Gladys, Larry shares one of the most tender relationships in the series. He supports her desires for freedom, understands her boredom with social rules, and acts as an ally whenever possible. When Bertha tries to control Gladys’ friendships and suitors, Larry serves as confidant and voice of reason.

Still, his protection never becomes condescending. Gladys, in turn, seems to understand her brother more deeply than their parents do. There’s something rare between them — genuine affection, without rivalry.

Marian Brook: near-romance or idealization?

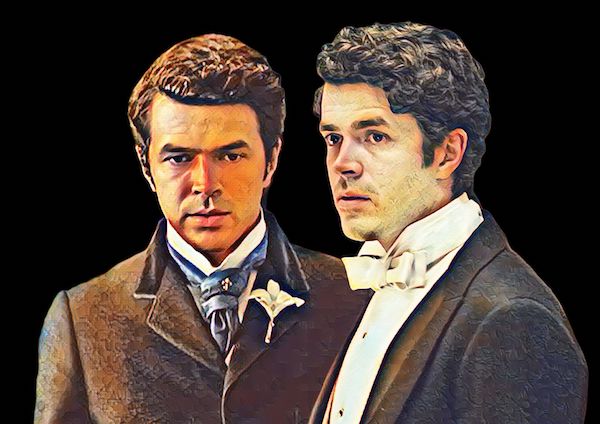

Since season one, there’s been subtle chemistry between Larry and Marian Brook, the young orphan who moves to New York to live with her aunts. Both are independent, cultivate personal interests (she in art, he in architecture), and have progressive spirits. But the romantic connection only becomes real at the end of season two, after Marian has suffered heartbreak with Tom Raikes, reluctantly accepted an engagement to Dashiell Montgomery, and Larry fell in love with Susan Blaine. In their final scene together, Larry seizes the moment and surprises Marian with a kiss. Fans of “Larian” went wild.

Now season three brings drama: Bertha opposes the romance, George approves, Agnes accepts. Marian and Larry get engaged, but obstacles are immediate: he goes away for a month to help in his father’s business and “lies” to Marian about attending a bachelor party at a brothel. When she finds out — in this Sunday night’s episode — she will question everything, including their bond. Will this be the perfect opportunity for Bertha to split them apart? How will Larry respond to Marian’s jealousy? What will Marian do? So many questions!

Did Larry Russell exist?

Historically, yes and no. Larry is fictional, but he perfectly mirrors a very real generation of American heirs at the end of the 19th century. Two names illustrate this perfectly.

William Kissam Vanderbilt, grandson of the founder of the Vanderbilt dynasty, was sophisticated, fluent in French, passionate about art, and responsible for commissioning Marble House — a mansion modeled after European palaces, symbolizing the family’s attempt to elevate its status.

George Washington Vanderbilt II went even further. He built the massive Biltmore Estate, dedicated himself to literature, collecting, and horticulture. He never held a position in the family business. He was reserved, sensitive — almost an aesthete. And like Larry, he created his own universe under the shadow of a brutal fortune.

Many other young men from New York’s elite — known as clubmen — shared this profile. Sons of magnates like Rockefeller or Morgan, educated at elite schools, are passionate about architecture, music, or sailing. They didn’t want to replicate their fathers. They wanted to correct them — or at least, refine them.

What he represents

In the end, Larry Russell represents the ideal of aesthetic regeneration in the new America. He is neither the romantic hero nor the seductive villain. He is the son of brutality who chooses beauty. The heir who looks at concrete and dreams of domes. The man who loves his family, but doesn’t repeat their mistakes. Who respects the past but wants to build — literally — a different future.

Larry symbolizes a social and cultural transition. He doesn’t shout, doesn’t threaten, doesn’t impose. But he’s there, present in every drawing room, every façade, every project. A new kind of aristocrat, made of tracing paper, elegant lines, and quiet strength.

And that’s why he exists. Even if invented. And we adore him. For now, at least!

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.