I was never particularly a fan of sci‑fi or horror, but I’m part of Sir Ridley Scott’s fan club. I grew up with his films, learned about cinema through them, and can spend hours praising them. Watching the first six episodes of Alien: Earth, the FX series coming to Disney in Brazil, I found myself once again electrified by Scott’s unwavering vision—about Art, Society, and Life. Across his varied filmography, the director consistently poses his questions, whether set in the present, the future, on Earth, or in the Universe.

Alien: Earth isn’t directed by him—it’s produced by him, just like the unjustly canceled Raised by Wolves, which has returned to my tortured heart through the new series premiering next week. And mark this: it’s incredible (remember, this praise holds double weight because I can’t stand horror, especially when mixed with sci‑fi, and yet I devoured the episodes wanting more).

Ridley Scott isn’t a filmmaker who predicts the future—he understands it. For more than four decades, Scott has built worlds where the clash between humanity and technology, environmental collapse, corporate domination, and emotional failure are central themes. Films like Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982) already mapped out a grim, cynical vision that now seems to have come to pass. His legacy is so prescient that science fiction itself begins to feel more documental than speculative. In 2025, with the release of Alien: Earth, another piece of that dystopian mosaic falls into place—and unsurprisingly, it reverberates with the dilemmas of Raised by Wolves, canceled prematurely but fundamental to understanding his vision.

Flawed humans, conscious androids

One of the most unsettling provocations Scott consistently makes is that perhaps humans aren’t the most evolved form of consciousness. Blade Runner is the most refined expression of this thesis: replicants—supposedly “less than human”—demonstrate more compassion, pain, and desire to live than the humans who hunt them. The central question—what makes us human?—is answered uncomfortably: empathy. And ironically, it is more apparent in artificial creatures.

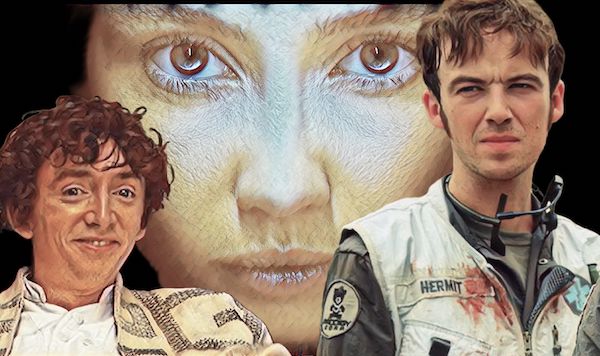

This idea is revisited in Raised by Wolves (2020–2022), where androids programmed to protect and love human children become more caring, sensitive, and consistent than the humans at war. Mother, the android protagonist, is both a weapon of mass destruction and a profoundly emotional maternal figure—capable of tenderness, rage, sacrifice, and grief. Her empathy is not “real” in a biological sense—it is constructed. But perhaps precisely for that reason, it is purer: her caregiving algorithm doesn’t fail from vanity, greed, or a domineering instinct. Humans, on the other hand, remain enslaved to those destructive impulses.

In Alien: Earth, this equation returns—now set in a world where humanity itself teeters on the edge of extinction, and the technology once created to serve becomes the only hope for survival—or the final threat. The parallel between androids preserving values and humans corrupting them is more than a narrative device: it mirrors how we increasingly delegate emotional and ethical intelligence to machines, while becoming broken algorithms ourselves.

“The greatest terror is not in space—it is inside us.”

— Ridley Scott, on Alien

A dead planet and corporate dominion

From Alien onward, Scott constructs futures where Earth is little more than a memory—or a burden. The planet, as we know it, becomes either destroyed or irrelevant. In Blade Runner, almost no one lives on Earth. In Raised by Wolves, it’s reduced to ashes after a religious-ideological war between atheists and fanatics. In Alien: Earth, it returns as a battlefield—yet there is no romance in its revival: the planet is dominated by megacorporations manipulating biotechnology and commodifying life itself.

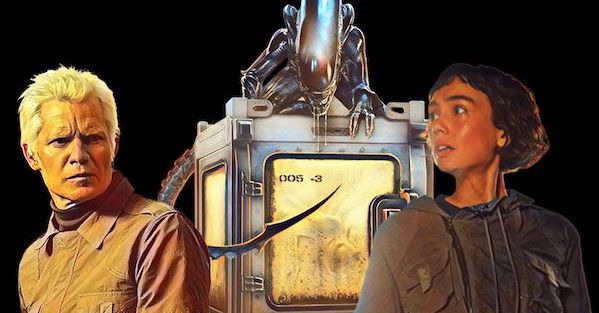

The Weyland‑Yutani corporation in Alien represents corporate greed incarnate: a company willing to sacrifice the entire Nostromo crew to capture the perfect alien organism as a biological weapon. In Alien: Earth, this archetype reappears in characters like Boy Cavalier—a young billionaire embodying the new face of dystopian capitalism—not as a suited CEO, but as a narcissistic genius manipulating humanity’s fate like a startup. Here, technology isn’t the villain: the villain is the unethical human using it.

The contemporary echo is unavoidable: we live under the rule of tech companies controlling data, affection, identity, and politics. Decades ago, Ridley Scott warned us that in the future, power would shift away from governments to corporations able to create—or destroy—worlds via code. And here we are.

Themes beyond sci‑fi: power, memory, legacy

Even outside of sci‑fi, Scott continues to explore the same themes. In Gladiator (2000), the Roman emperor represents moral decay within a system where absolute power corrupts absolutely. The arena becomes a spectacle of death distracting a crumbling society. In House of Gucci (2021), ambition, manipulation, and the collapse of a dynasty echo the corporate dramas of Blade Runner and Alien. In Napoleon (2023), vanity drives destruction more than conquest.

These films suggest that, for Scott, geniuses—whether emperors, fashion moguls, or inventors—are also agents of collapse. Intelligence without empathy doesn’t save: it kills. Genius is dangerous when divorced from human fragility.

The “genius” is not a hero. They are the catalyst for collapse. Whether a programmer building androids, an emperor dreaming of immortality, or a CEO promising to reinvent human DNA, Scott portrays these figures as tragic characters: smart enough to build a new world, yet emotionally unprepared to live in it.

“Empathy is the only trait that distinguishes a human from a machine. But not all humans have it.”

— Scott, in an interview about Blade Runner

“Alien: Earth” and the Neverland of machines

In Alien: Earth, Ridley Scott returns to the Alien universe with a bold narrative twist: for the first time since the original films, the xenomorph threat lands on Earth—a planet ravaged not by extraterrestrials but by humanity itself. Created by Noah Hawley, the series takes place decades after the original incursions and functions as both a reinvention and thematic continuation.

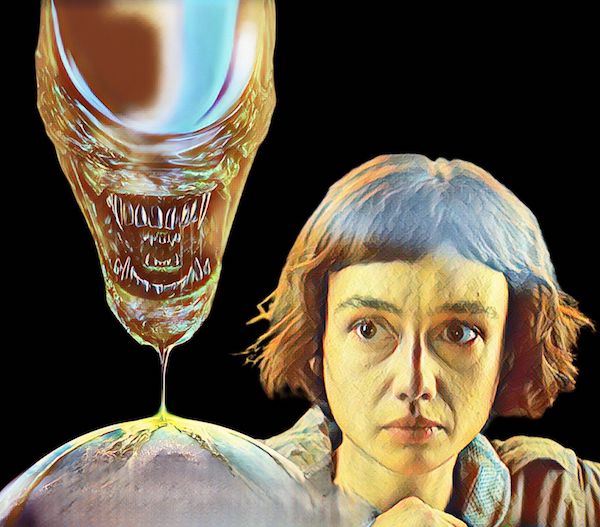

Central to the story is Wendy—tied to the experiments of Prodigy, the billionaire company promising to reshape humanity through genetic engineering and biotech. Meant to be a passive link in the project, Wendy emerges as the most human figure in the series—not because of her biology, but her ability to feel and question. She becomes the bridge between xenomorphic monstrosity and human rational cruelty. The conflict shifts from “alien vs. human” to “consciousness vs. system.”

Scott and Hawley weave a powerful allegory: Wendy is a sort of Wendy Darling—the girl from Peter Pan—trapped in a biotech Neverland, manipulated by adults. But in this case, the “Peter” is Boy Cavalier—a young, narcissistic, perverse billionaire promising freedom and reinvention but exercising absolute control over everyone around him. He is the new “tragic genius” in Scott’s universe: more seductive, cruel, and contemporary. It’s as if Tyrell, Zuckerberg, Musk, and a spoiled child fused into one being.

The connection with Raised by Wolves is clear: just as Mother was programmed to protect but ends up generating destruction out of love, Wendy symbolizes hope for a new generation carrying the violence of the past within her own body. The dilemma of programmed empathy resurfaces: Wendy can feel more than those who created her—but is that enough?

In this context, the alien threat becomes more symbolic than literal. The xenomorphs are products of corporate delirium, uncontrolled scientific hubris, and vanity. But the real terror is that no one seems to remember what “life” means. Wendy is viewed as code. The planet is an asset. Fear is a tool of persuasion. The series deconstructs the sci‑fi genre itself by showing that horror may not come from space—but from humanity’s desire for total control.

A dark mirror

Viewed together, Ridley Scott’s body of work forms a grand mural of the 21st century. He is not an optimistic author. His stories don’t promise salvation—they demand clarity. If androids can love more than we can, it’s not because they’re magical—it’s because we were programmed to fail. But by making that failure visible, Scott gives us something invaluable: the chance to reprogram ourselves.

In Alien: Earth, as in Raised by Wolves or Blade Runner, there is still resistance. There is still questioning. The question remains: is it even worth being human? And the answer, perhaps, lies less in our genes and more in our choices. Ridley Scott knew that 40 years ago. We’re still trying to understand it.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.