In Brazil, the name “Zambelli” has been heard so much lately—in the news and on social media—that my mind took an involuntary—and far more interesting—detour to another Zambelli, one truly worthy of the name: Carlotta Zambelli, the ballerina. A figure who had always hovered at the edge of my awareness without ever leaving a deep imprint—until now.

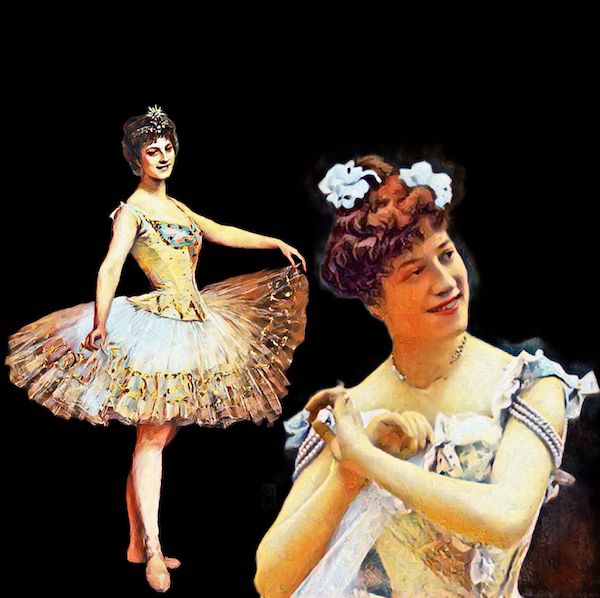

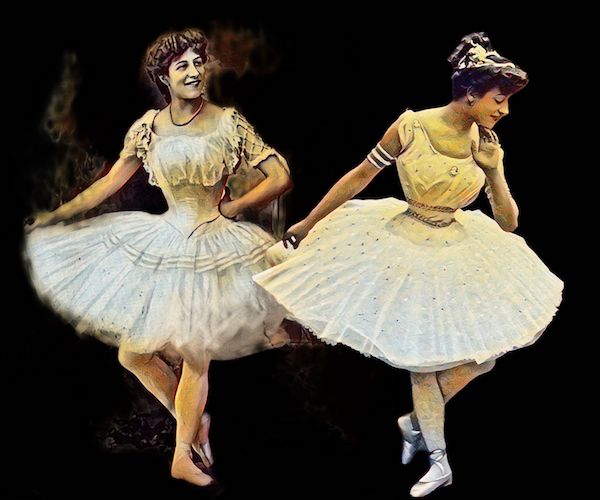

My first memory of her, oddly enough, was not especially flattering. I was leafing through one of those old compendia on the history of ballet when I came across a disquieting, almost comical image: Zambelli and Antonine Meunier, in swapped costumes (en travesti), in a production of Les Deux Pigeons. The caption was merciless. The photo was used to illustrate the “rock bottom” to which French classical ballet had supposedly sunk at the end of the 19th century, before the revolution brought by Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes. It was an accusation disguised as documentation.

But perhaps it was time to revisit Zambelli with more generosity—and context.

Italian by birth, Carlotta Zambelli was born in Milan in 1875—150 years ago now—and trained at La Scala’s prestigious ballet school, where she studied under Adelaide Viganò and Cesare Coppini, exponents of the Italian school, renowned for its technical rigor, daring jumps, and spins of near-mathematical precision. At 19, she was brought to Paris by the then-director of the Opéra, Pedro Gailhard, and quickly won over the French stage with a performance of fifteen fouettés in a divertissement of the opera La Favorita. It may seem little today, but at the time it was a shock. The gold standard—32 fouettés—had only been established three years earlier by Pierina Legnani in the premiere of Cinderella in St. Petersburg.

Zambelli didn’t reach 32, but she caused enough of a sensation to be promoted to étoile of the Paris Opera in 1898. Not bad for a foreigner in a system that, not long after, would close its doors to non-French ballerinas. She remained prima ballerina until 1930—three decades of absolute prominence in one of Europe’s most conservative houses.

And it wasn’t just about holding a position. Zambelli created leading roles in works such as Namouna (1908), Javotte (1909), España (1911), Sylvia (1919), Taglioni chez Musette (1920), and Cydalise et le chèvre-pied (1923). In 1927, already a mature artist, she danced in Impressions de music-hall by Bronislava Nijinska—a near-poetic gesture of bridging tradition and avant-garde. Nijinska, sister of Nijinsky and one of ballet’s great modern voices, saw in her what many had stopped seeing: vigor, elegance, and stage intelligence.

One fascinating detail: in 1901, Zambelli went to St. Petersburg and performed at the Mariinsky Theatre, the heart of Russia’s imperial ballet, where she danced Giselle, Paquita, and Coppélia. She was the last foreigner to hold that position before artistic nationalism closed the gates. She stood among names like Mathilde Kschessinska, Olga Preobrajenska, and Anna Pavlova—and still held her ground.

Even after leaving the stage, Zambelli did not leave dance. Quite the opposite: she taught at the Paris Opera School until 1955 and ran her own academy. She trained an entire generation: Yvette Chauviré, Solange Schwarz, Odette Joyeux, Lycette Darsonval—names that kept French classical dance alive through the first half of the 20th century. She wasn’t just a ballerina—she was a link between centuries.

But if we speak so much of her, why does there seem to be so little of her? That’s the question. Like so many artists of her time, Zambelli lived before the era of mass documentation. Cinema was still in its infancy, records are scarce. Fortunately, there are fragments of film, shot in studio, showing her technique late in her career: clean jumps, controlled entrechats, a regal bearing that says more than a thousand pirouettes. I used an excerpt from Delibes’ Sylvia suite—which she danced in 1919—to score these images. It felt melancholic, but also right.

Carlotta Zambelli died in 1968, at the age of 92, in the same Milan where she was born. She received France’s Legion of Honour, the country’s highest distinction, and remains a quiet reference for those who know the history behind the red curtains.

She may never have been revolutionary in the mold of a Pavlova or an Isadora Duncan, but her importance lies precisely there: preserving the foundations while the world danced in new directions.

And today, when I hear someone say “Zambelli” with disdain, I think of the other one. The one who spun fearlessly on the Garnier stage. The one who entered the Mariinsky with fouettés in her body and fire in her feet. And I smile. Because that Zambelli, indeed, left a legacy.

https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMSKQYLn2/

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.