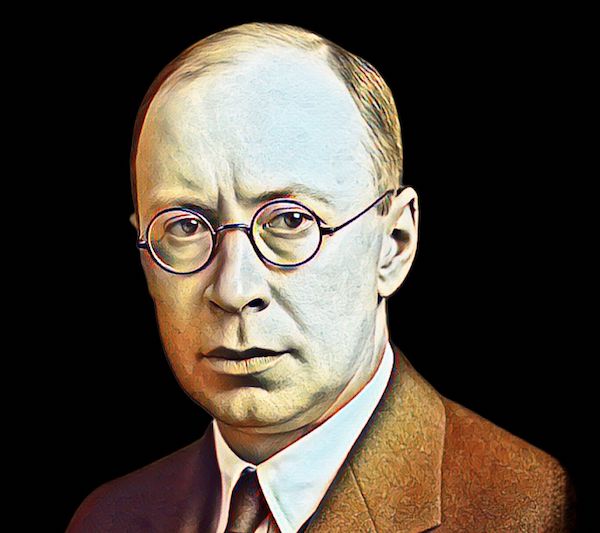

Sergei Prokofiev composed Romeo and Juliet between 1935 and 1936, during an important transitional period in his life. After years abroad, he returned to the Soviet Union and sought to balance his modern musical language — marked by dissonances, biting humor, and inventive rhythms — with the demands of official Soviet aesthetics, which called for clear melodies and narratives accessible to the public. Adapting Shakespeare was no accident: a universal classic, full of drama, capable of appealing to both erudite and popular audiences.

However, the process was turbulent. Prokofiev’s initial idea featured a different ending, in which Romeo and Juliet survive, but the Bolshoi rejected this, demanding fidelity to the original tragedy. There were disputes over choreography and delays, and the music was first heard in the form of a concert suite. The suite quickly drew attention, especially Dance of the Knights, which stood out as a grave, imposing piece with an ostinato suggesting both aristocratic solemnity and imminent threat.

The strength of the piece lies in its combination of weight and clarity. The main theme, with deep strings and powerful brass, is memorable and unmistakable. In the ballet, it marks the entrance of the Capulet family, establishing an authoritarian and closed presence. Outside the theater, its almost cinematic tone made it a frequent soundtrack for TV shows (like the British The Apprentice), films, commercials, fashion shows, and sporting events. Just a few minutes of this music evoke power, drama, and solemnity — pure gold for any production wanting to make an impact.

Moreover, Dance of the Knights carries the mark of Prokofiev the chess player. He was not merely a casual player: he frequented clubs, played with masters like Capablanca and Botvinnik, and saw a direct analogy between chess and musical composition. The piece is structured like a chess game: it starts with a solid opening, develops with advances and retreats, reaches a climax of total attack, and ends with a sonic checkmate.

This connection becomes even clearer when we place Dance of the Knights side by side with a real game Prokofiev played against Capablanca during a simultaneous exhibition in Moscow, 1936:

Opening (Thematic Exposition)

In music: a grave, martial theme establishes the territory — the Capulets are imposing and dangerous.

In chess: Prokofiev opens with e4, Capablanca responds with the Sicilian Defense (c5), defining a strategic battle from the start.

Parallel: both announce a tense, high-stakes contest.

Middlegame (Development and Conflict)

In music: a lyrical, softer theme representing Juliet emerges but is soon interrupted by the heavy original motif.

In chess: Prokofiev attempts an attack on the king’s flank, but Capablanca counters in the center, undermining his position.

Parallel: the “soft voice” in the music is like Prokofiev’s promising initiative, under constant threat of counterattack.

Climax (Maximum Tension)

In music: the orchestra returns forcefully to the martial theme, now denser and more relentless.

In chess: Capablanca sacrifices a pawn to open lines against Prokofiev’s king — a tactical blow that shifts the game.

Parallel: the return to the main theme symbolizes the growing pressure of an inevitable attack.

Finale (Resolution)

In music: ends abruptly with dry, heavy chords, a sealed fate.

In chess: Prokofiev resigns facing an inevitable checkmate.

Parallel: both music and game’s structure pointed to this inescapable conclusion from the start.

This strategic reading makes Dance of the Knights hypnotic: it’s not just a set of impressive notes, but a rigorously crafted narrative.

In the second season of Wednesday, in the premiere episode “Here We Woe Again,” Dance of the Knights appears as a sonic presence that says everything without words: order, hierarchy, tension, and a touch of dark irony — perfect for the world of Nevermore and Wednesday Addams’s own aura. It’s as if Prokofiev composed the soundtrack for the Capulets’ ball, and decades later, the same music fits the macabre, clever dance the series builds.

Crossing nearly 90 years, Dance of the Knights shows how a work created for ballet can become a popular icon, moving between high culture and mass entertainment, while keeping its dramatic power intact — like a chess game that still surprises those who study it long after it’s played.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.