From the very first scene she appears in, Peggy Scott makes it clear that her wardrobe is no mere period ornament—it’s a language. The way she dresses says as much about her as her lines and gestures, and it’s impossible not to notice the care costume designer Kasia Walicka-Maimone takes in making each gown a chapter in the life of this young Black writer navigating a world constantly trying to define her limits.

The inspiration for Peggy’s wardrobe stems from a meticulous immersion in the fashion of the 1880s, combining historical sources—such as fashion magazines, studio photographs, and preserved garments in museums—with the painterly aesthetics of artists like John Singer Sargent and Giovanni Boldini. It’s from this blend that the balance between historical fidelity and contemporary cinematic appeal emerges: the silhouettes remain true to the period, but the camera captures in them a certain freshness.

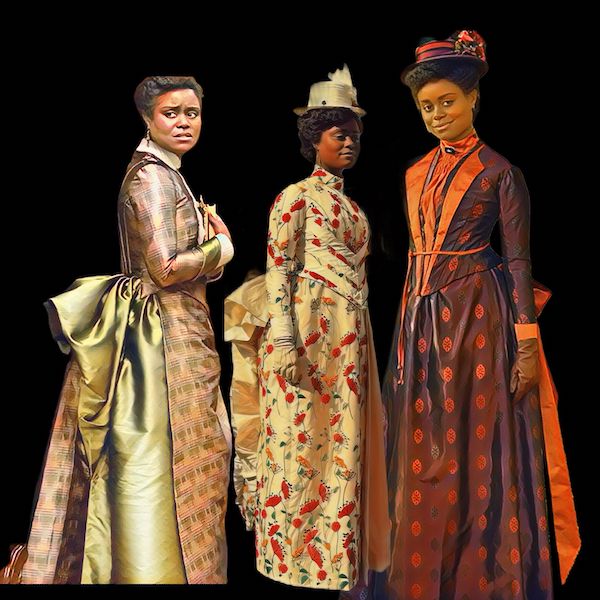

The structure of the garments follows the logic of the era: waists tightly cinched by corsets, skirts with volume concentrated in the back, and the omnipresent bustle, which shaped the body to the Victorian ideal of elegance. However, what could feel rigid becomes, in the hands of the costume team, an extension of Peggy’s personality. The fabrics—taffeta and satin silks, deep velvets, brocades, and lace—are chosen not only for their luxury but for their narrative power. Each texture tells something: the stiffness of taffeta can symbolize restraint and self-control; the fluidity of a lighter silk, moments of openness and freedom.

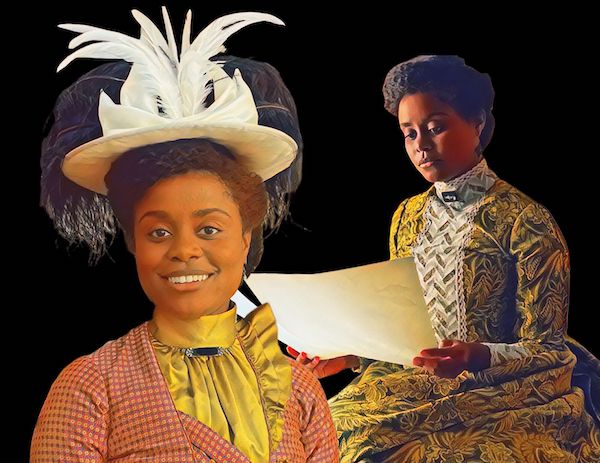

Peggy’s color palette is particularly revealing. In family and domestic scenes, lighter, softer tones dominate—creams, dusty pinks, washed blues—evoking the notions of respectability and delicacy that white society expected from an “acceptable” upper-middle-class Black woman in Brooklyn. But when she moves into spaces where she must assert presence and authority—such as New York’s aristocratic homes or the Newport social scene—jewel tones emerge: sapphire blues, deep greens, burgundy, and even hints of gold. These are colors that take up space, project confidence, and refuse invisibility.

The motifs and embroidery decorating her dresses also work as visual cues. Butterflies, flowers, and delicate patterns appear as symbols of femininity and transformation, but they also signal access to skilled craftsmanship and high-end ateliers—an important detail to mark her social background and family support network. The use of bolder prints or elaborate appliqués is carefully measured: never excessive, but enough for Peggy to stand out without violating the unspoken rules of the social codes she navigates.

This attention to detail is deliberate. The evolution of Peggy’s costumes closely tracks her personal journey. Early on, we see her in practical, well-tailored clothing, in more discreet colors, appropriate for her role as a daughter and young professional trying to secure her place. As the narrative progresses and her visibility increases—whether in journalism or in higher-prestige social events—her clothing gains complexity: more layers, richer textures, more embellishment. It’s as if every new step forward is sewn into the hem of her skirts.

What’s most striking is that this evolution isn’t purely linear or upward. In moments of personal crisis or conflict, the wardrobe pulls back: more sober colors, more restrained cuts, less eye-catching fabrics. It’s a visual reminder that, for a Black woman in Gilded Age New York, dressing was also a strategy for survival. Choosing a neutral shade or a less elaborate hat could mean avoiding hostile stares or whispered comments—and the series translates that with subtlety, without the need to spell it out.

The final symbolism of Peggy’s costumes is that of a narrative stitched both inside and out. On the outside, there’s the brilliant surface of late 19th-century high fashion: the silhouette, the luxurious fabrics, the vivid colors made possible by the new synthetic dyes of the period. On the inside, there’s a personal, almost secret code that speaks of identity, ambition, resilience, and the art of negotiating spaces. Peggy doesn’t just wear dresses; she wears messages. And in the attentive reading of each pleat, tuck, and embroidery lies the portrait of a woman who refuses invisibility and uses fashion as one of her sharpest tools.

That is the true power of costume design in The Gilded Age: not simply to reconstruct a time, but to reveal the layers of a character who knows—perhaps better than anyone—that the right dress can open doors… or close them forever.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu