Some films don’t just premiere — they settle into the collective imagination as if they’d always been there, ready to shape the way we see an entire world. Black Swan, released in 2010, is one of those rare cases. A hybrid of psychological drama, body horror, and a study of perfectionism, Darren Aronofsky’s work changed the way cinema portrays ballet, revealing that beneath the ethereal surface of dance lies fertile ground for obsession, paranoia, and self-destruction.

This month, Searchlight Pictures is bringing this classic back to the big screen — and not just any big screen. In partnership with Imax, the studio is launching Black Swan 15th Anniversary Exclusive: Remastered for Imax, showing on more than 200 screens on August 21 and 24. It’s the first time the film gets the IMAX treatment, promising to reveal “the full cinematic scope and depth” of the work, with a new restoration and even a commemorative poster for early ticket buyers. It’s the chance to see Natalie Portman wage bloody battle against a pesky hangnail (literally) on the widest screen imaginable — and to revisit one of the most striking portrayals of art and madness of the 21st century.

Before Black Swan: a long-standing marriage between ballet and instability

Long before Aronofsky, cinema had already realized that ballet was an ideal setting for stories of obsession and tragedy. In The Red Shoes (1948), by Powell and Pressburger, the protagonist is consumed by her devotion to dance, unable to balance love and career until a fatal end. In Suspiria (1977), Dario Argento turns a ballet school into a front for a coven of witches. Even Limelight (1952), by Charles Chaplin, although not about ballet, examines the emotional fragility of artists in decline. In all these cases, the stage is the veil that hides backstage sacrifice and pain.

Ballet is, by nature, cinematic: the weightless, controlled perfection the audience sees contrasts with the military discipline, exhausted bodies, and psychological pressure behind the scenes. That contrast is what cinema feeds on for intense storytelling.

The seed of Black Swan and Aronofsky’s personal influence

Darren Aronofsky didn’t stumble upon ballet by accident. The director, who had already delved into self-destructive characters in Pi (1998), Requiem for a Dream (2000), and The Wrestler (2008), grew up in Brooklyn with a sister who was a professional ballerina. From early on, he witnessed the rehearsal routines, the aesthetic pressure, and the competitive environment of dance. Black Swan began as an idea closer to All About Eve, centered on artistic rivalry, but quickly absorbed elements of psychological horror, Cronenberg-style body metaphors, and the concept of the double (doppelgänger).

Casting, dedication, and controversy

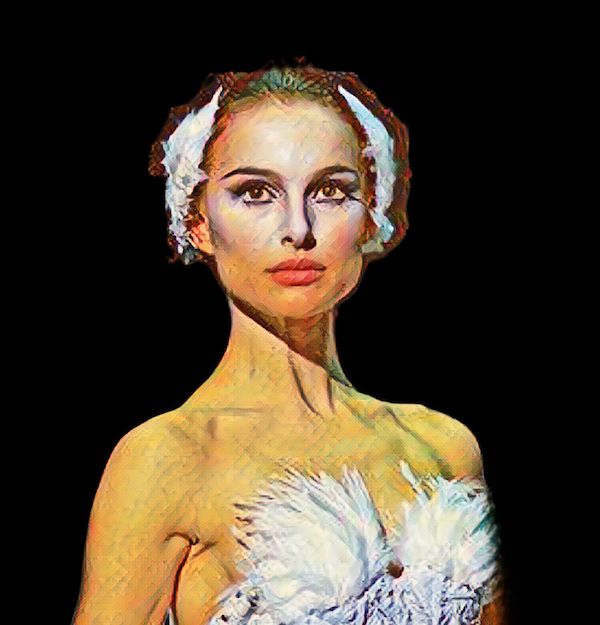

When he cast Natalie Portman as Nina Sayers, Aronofsky wanted more than a good actress — he wanted someone willing to push her body and mind through a rigorous process. Portman trained in ballet for months, lost a significant amount of weight, and absorbed the posture and gestures of a ballerina. But for the more complex sequences, the production relied on Sarah Lane, then a soloist at the American Ballet Theatre, as a dance double. Controversy erupted when Lane accused the production of downplaying her work, sparking debate about credit and authenticity in cinema.

Alongside Portman, Mila Kunis played Lily, the rival who radiates confidence and instinct — someone Nina both fears and desires. Vincent Cassel, as artistic director Thomas Leroy, acted as a catalyst, manipulating and pressuring Nina to push beyond her limits.

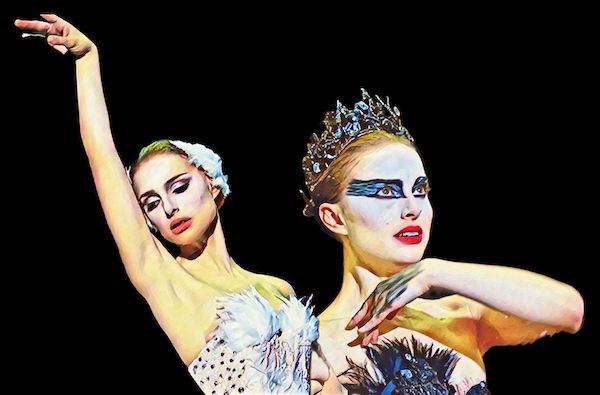

Nina Sayers: purity, shadow, and collapse

Nina is the perfect Odette: fragile, controlled, impeccable. But to become Odile, she must find her wild side — something she represses obsessively. Aronofsky constructs her psychological deterioration as a ballet of paranoia, visions, and hallucinations: feathers sprouting from her skin, nails torn, reflections moving on their own. It’s a narrative about fractured identity and the cost of chasing perfection — when perfection, in reality, is impossible.

Ballet as horror: the monster within the ballerina

Unlike Suspiria, there are no witches or external curses here. The “monster” is Nina, and her transformation is internal — a mental battle that manifests in the body. This choice keeps the film ambiguous: is it a metaphor about mental health, or a literal account of metamorphosis? Aronofsky has never answered, and audiences remain divided.

For general viewers, Black Swan offered a stylized, hypnotic glimpse into ballet. For dancers, the portrayal felt exaggerated, yet respectful. “It’s not a joke,” said Chloe Misseldine of the American Ballet Theatre. “Everything is exaggerated, but the film treats ballet seriously.”

The ending and its ambiguity

In the final performance, Nina injures herself but dances to the end. As she receives her ovation, she says, “I felt it. Perfect.” Does she die? Was it a hallucination? Aronofsky leaves the answer open. What matters is that, for Nina, that moment was the peak — and perhaps, the last.

The impact and the numbers

Released in December 2010, the film grossed over $329 million worldwide on a budget of about $13 million. It received five Oscar nominations — Best Picture, Director, Cinematography, Editing, and Actress — and won Best Actress for Natalie Portman. Her performance also earned her the Golden Globe, SAG Award, and BAFTA.

Black Swan directly influenced ticket sales for productions of Swan Lake and reinforced the link between ballet and darker narratives. Fifteen years later, its costume (the black tutu, tiara, and dramatic makeup) and lines remain cultural icons.

15 years later: IMAX, nostalgia, and new readings

The IMAX screenings in August are not just a celebration; they are a reminder of the film’s aesthetic power. Seeing Matthew Libatique’s cinematography on a giant scale, with Clint Mansell’s unsettling score expanded, should feel like rediscovering the movie. It’s also a nod to new audiences: for those who saw it streaming or on a small screen, now is the chance to experience Black Swan as it was intended — immersive, suffocating, and beautiful.

Meanwhile, Aronofsky is already set to return to theaters with Caught Stealing, starring Austin Butler and Zoë Kravitz, premiering days after these screenings. Portman continues to diversify her roles, recently appearing in Fountain of Youth alongside John Krasinski.

Fifteen years later, Black Swan remains the most visceral example of how cinema can explore beauty and destruction in the same dance step. A story that, like The Red Shoes and Suspiria, understands that the stage is only the surface — and that behind the applause, there is always a price.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu