Ophelia is perhaps the most emblematic of Shakespeare’s “present absences.” She occupies little stage time, speaks less than any other central character, and yet has become the most unforgettable image of Hamlet. Daughter of the court advisor Polonius and sister to Laertes, she is introduced as the obedient “good daughter,” the intended bride of Prince Hamlet — shaped by duty, by the constant watch of men, and by court life. At first, she is a discreet figure, almost invisible, always answering “I shall obey, my lord” to her father’s commands. But the political and emotional machinery tightening around her narrows her path until she can no longer breathe — and finally, no longer stand.

Her apparent fragility hides an acute sensitivity. When Hamlet decides to feign madness to unmask his uncle, Ophelia becomes an unwitting target of his game. The brutal and public break (“Get thee to a nunnery”) is only the first blow. Her father’s death at Hamlet’s hands severs her last anchor to stability. What follows is one of literature’s most beautiful and painful descents: she begins to speak in fragments, singing old ballads (“How should I your true love know…”, “Tomorrow is Saint Valentine’s Day”), handing out real and symbolic flowers (“There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance; and there is pansies, that’s for thoughts”), and stringing together proverbs, sayings, and disjointed memories. It is the speech of someone whose mind has unraveled, but also of someone still trying to communicate — a coded lament mixing loss, eroticism, guilt, and superstition.

Dramatically, Ophelia is the shattered mirror of Hamlet. He can explore madness as artifice; she sinks into it without return. Her fall propels Laertes toward vengeance, humanizes the political plot, and inserts an intimate lament into the play: the price women pay when power turns life into a chessboard. Her death — narrated by Gertrude in one of Shakespeare’s most poetic passages (“There is a willow grows aslant a brook…”) — is a lyrical suspension: the leaning willow, the stream, garlands of flowers, the dress floating “like mermaids,” until the weight of the fabric drags her under. Is it an accident? Suicide? The funeral, with “maimed rites,” suggests the court suspects a “desperate hand” — in the Christian universe of the play, a sin punished even after death.

Ophelia did not exist in the original sources of the Hamlet legend. Shakespeare invented her, though her name appeared a century earlier in Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia, likely derived from the Greek ōphéleia, meaning “help.” Since then, she has been a lens through which to discuss “female madness” and, in the 19th century, a favorite subject of the Pre-Raphaelites. John Everett Millais painted her between 1851 and 1852, with Elizabeth Siddal posing for hours in a bathtub to recreate the sensation of a body submerged. The model fell ill during the process, adding to the painting’s myth. The image — billowing dress, open hands, floating flowers — became synonymous with Ophelia. Later came J. W. Waterhouse’s variations, Eugène Delacroix’s romantic visions, and Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs of Ellen Terry in costume. Every generation has found its way to freeze that moment between life and drowning.

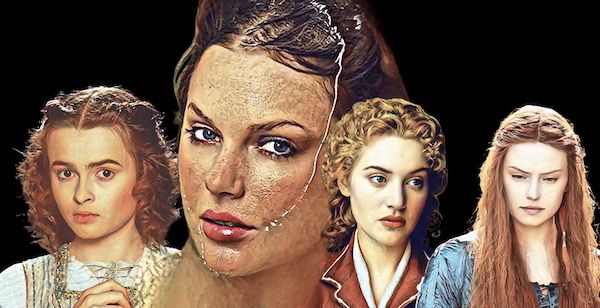

On stage, Ophelia was embodied by Ellen Terry in the 19th century, Jean Simmons in Laurence Olivier’s film (1948), Helena Bonham Carter under Franco Zeffirelli’s direction (1990), and Kate Winslet in Kenneth Branagh’s full-length Hamlet (1996). In 2009, Gugu Mbatha-Raw played her opposite Jude Law and brought in consultations with psychiatrists to map the character’s mental state with precision. Each actress faces the challenge of not turning pain into pure decoration — of avoiding an Ophelia who is only a beautiful, sad picture.

And it wasn’t just theater and painting that claimed her. In ballet, Hamlet has been staged with Ophelia’s madness and drowning transformed into delicate yet physically demanding solos, requiring the dancer to translate mental collapse into movement oscillating between rigidity and surrender. In music, composers such as Hector Berlioz created songs inspired by her (La mort d’Ophélie), Gabriel Fauré set the text to a near-funereal lament, and even the band The Lumineers invoked her name as a symbol of loss and endangered purity.

Recent cinema tried to reclaim her voice. In Ophelia (2018), directed by Claire McCarthy and starring Daisy Ridley, the story is told from her perspective. Based on Lisa Klein’s novel, the film gives the character agency: we see her thoughts, strategies, and a version in which she doesn’t die in the stream but escapes, reinventing her fate. Naomi Watts plays Gertrude, Clive Owen is Claudius, and George MacKay portrays a more vulnerable Hamlet. The cinematography, saturated in greens and blues, echoes Pre-Raphaelite paintings, and the score blends medieval song with ethereal atmosphere to keep us firmly in Ophelia’s gaze — not the court’s silent view of her.

Famous lines help “explain” Ophelia as much as they reveal her:

- “O, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown!” — about Hamlet, but also about herself, as if she senses her fate.

- “There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance… and there are pansies, that’s for thoughts.” — the flower scene, where each plant is a coded message.

- “Lord, we know what we are, but know not what we may be.” — a flash of philosophical insight in the middle of her breakdown.

- Gertrude’s entire account, turning death into visual poetry.

Four centuries later, Ophelia still haunts us because she embodies questions that never age: how far can loyalty go? How do you survive private grief when you live on a public stage? How do you resist when you are a “supporting character” in your own life? Perhaps that’s why pop culture refuses to let her sink. Taylor Swift, who once turned Shakespeare into a chorus in “Love Story,” has included a track called “The Fate of Ophelia” on her upcoming album The Life of a Showgirl. Fans claim the promotional images directly reference Millais’s painting, with aquatic flowers and flowing dresses. It’s a signature Swift move: reclaiming a female figure crushed by traditional narrative and returning her to song as the protagonist.

Ophelia began as a small role, meant to reflect another’s tragedy. But she left the play and crossed centuries, languages, screens, stages, and scores. She lives in Millais’s brush, in Berlioz’s voice, in a ballerina’s pointe shoes, in Daisy Ridley’s close-up — and, soon, perhaps, in Taylor Swift’s melody. A character Shakespeare erased in the final act, but whom the world refuses to let die.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu