A true crime mystery in classical music? Yes, it can be told that way: the gossip that Antonio Salieri poisoned Mozart was born almost at the same time as the composer’s untimely death. Mozart died in Vienna in 1791, at the age of 35, from a sudden and poorly explained illness. The death certificate cited “miliary fever,” a diagnosis so vague it created more confusion than clarity. And, as with every unexplained death, rumors spread quickly.

Some began to suggest that Mozart had not died by chance, but as a victim of intrigues at the imperial court. And who was there, with high office, prestige, and influence? Antonio Salieri, the court composer, was far more respected institutionally than Mozart, who was seen as a rebellious and difficult young man. The scene was perfectly set for gossip to thrive: the genius struck down early, the rival at the center of power, a court full of intrigue.

The rumor might have died there, like so many backstage legends. But in 1830, nearly forty years later, it gained artistic fuel. The Russian poet Alexander Pushkin wrote a short play called Mozart and Salieri, in which Salieri is portrayed as a man consumed by envy, unable to accept that Mozart, despite his childish and vulgar behavior, received the gift of music directly from God. In the play, Salieri poisons his rival. Pushkin turned gossip into myth.

The story spread even further when Rimsky-Korsakov set Pushkin’s text to music, creating the opera Mozart and Salieri (1898). The idea that the mediocre composer had assassinated the genius began to cement itself as cultural truth.

And then came the episode that sealed the legend. Already elderly, in the early 19th century, Salieri suffered from mental illness and reportedly said, in moments of delirium, that he had poisoned Mozart. Witnesses of the time recorded these “confessions,” and, of course, the words spread like wildfire: the accused himself admitted to the crime! But it wasn’t so simple. Later, Salieri denied it, said he had never harmed his rival, and on his deathbed, he reaffirmed his innocence. In other words, the “confessions” were more the product of mental confusion than revelation. Still, who can resist a cursed phrase like that? It was enough to cement the legend.

And why did this gossip stick so strongly? Because it dramatized a universal dilemma: resentment in the face of genius. Salieri was respected, disciplined, and recognized. Mozart was scandalous, childish, but unsurpassed in music. The contrast was too perfect not to become a narrative. And 19th-century Romanticism adored the figure of the misunderstood genius, persecuted and cut down too soon. Mozart’s premature death fit this imagination like a glove.

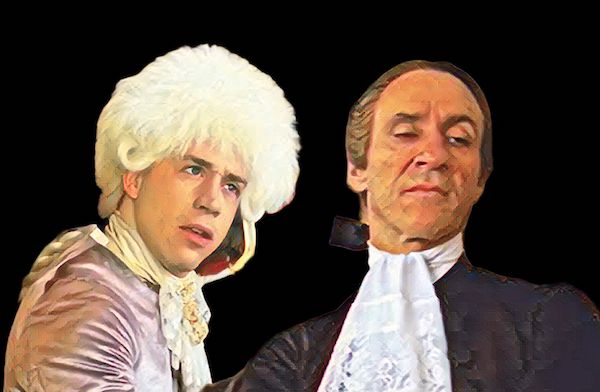

From there to pop culture was only a step. Peter Shaffer tapped into this story in 1979 when he wrote Amadeus, and then cinema, in 1984, brought this literary version to its peak, transforming gossip into Shakespearean tragedy. Today we know, based on medical studies, that Mozart most likely died from complications of rheumatic fever, bacterial infection, or kidney failure — not poison. But, as in every great “historical true crime,” the legend turned out to be far tastier than the truth.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu