When we think of Shakespeare on screen, it’s almost inevitable to remember Shakespeare in Love, the 1998 film that reinvented the playwright’s youth as a romantic comedy full of poetic license. There, Joseph Fiennes played a William Shakespeare madly in love with Gwyneth Paltrow’s Viola—an invented muse to justify the creation of Romeo and Juliet (with strong hints of Twelfth Night). No commitment to chronology, no respect for sources: it was pure fantasy, a delightful invention that worked beautifully in Hollywood. The result? Seven Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Actress for Paltrow, cemented in pop culture the image of Shakespeare as a seductive, passionate figure, as fictitious as it was irresistible.

Hamnet, in turn, takes the opposite path. Instead of romanticizing the genius, it turns inward, into his home, into the intimate world he shared with his wife Agnes Hathaway and their children. Irish author Maggie O’Farrell, who won the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2020, started from an unavoidable historical fact: Shakespeare and Agnes lost their son Hamnet in 1596, at the age of 11. This real, irreversible grief remained for centuries as a footnote in biographies. O’Farrell expands it into a novel—and in doing so dismantles the crystallized image of Shakespeare as a romantic icon, revealing instead the man, the husband, the grieving father.

The life of William and Agnes: encounters, children, and losses

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon and, still very young, impregnated Anne Hathaway—renamed Agnes in O’Farrell’s book. She was eight years older, from a family of some local reputation, and the marriage in 1582 was practically inevitable: Agnes was already pregnant. Their first child, Susanna, was born soon after. Then came the twins Hamnet and Judith, baptized in 1585.

From what little history has preserved, we know that William soon went to work in London, immersed in the theater, while Agnes remained in Stratford, caring for the children. The distance, as scholars imagine and O’Farrell narrates, did not mean emotional absence but rather a division of roles. The Hathaway household was marked by domestic joys and by the shadow of the plague ravaging England.

Tragedy came early: Hamnet died in 1596, at age 11, probably of the plague. For a couple who had already faced infant mortality so closely (Judith herself nearly died as a child), it was an irreparable blow. Agnes lost her son; William, it seems, threw himself into the theater to sublimate his grief. Only a few years later, Hamlet premiered. Coincidence? Hard to believe.

Maggie O’Farrell’s novel: grief turned into literature

In Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell makes Agnes the protagonist. Far from the invisible wife so often reduced in traditional biography, she appears as a woman connected to nature, with almost mystical gifts, endowed with singular strength. The narrative alternates between the present—Hamnet’s illness—and flashbacks to the couple’s early relationship, their marriage, and domestic life.

More than a biography, it is a poetic reinvention. The focus is not on Shakespeare but on Agnes and her intimacy with her children, and her attempt to save Hamnet. The novel builds the idea that grief was, in some measure, transformed into artistic creation: Hamlet, written only a few years later, not only shares the name but plunges into questions of death, memory, and legacy.

Critics unanimously praised the literary achievement. Hamnet was hailed as one of the great works of historical fiction of the decade, acclaimed for its lyrical writing and for giving humanity back to figures stiffened by history.

The final scene: Agnes before Hamlet

The most moving point of the novel is its final scene. After years of silence and distance, Agnes travels to London and enters the theater where her husband’s new play is being staged. Still in mourning, she hears the title—Hamlet—and immediately feels the stab of remembrance.

As the play unfolds, Agnes sees her son reflected in every gesture, in every word spoken by the Prince of Denmark. It is as if Hamnet had been brought back to life, but at the same time as if his absence were even more unbearable. O’Farrell describes Agnes watching the stage and realizing that Shakespeare had transformed private tragedy into a monument: Hamlet itself is the epitaph, the living gravestone of the lost child.

There is no single highlighted quotation, but readers recognize echoes of the great soliloquies—the melancholy of “To be or not to be,” and the acceptance of fate in phrases like “There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow.” It is as if Agnes were hearing, in the words of the prince, the words she never heard from Hamnet.

The film adaptation: Chloé Zhao and her sensorial style

In 2025, Hamnet came to the screen under the direction of Chloé Zhao, Oscar winner for Nomadland (2020). Zhao’s style is unmistakable: ethereal images, near-documentary naturalism, and an emphasis on landscapes and the relationship between people and nature. In Hamnet, she translates that signature to the Elizabethan world, creating what she herself described as a “fairy tale for adults.”

The film, produced by Sam Mendes and Steven Spielberg, was shot in Wales in 2024 and premiered in September 2025 at the Toronto International Film Festival. It will open in the U.S. in limited release on November 27, 2025, and expand nationwide on December 12, with international distribution by Universal.

Cast and music

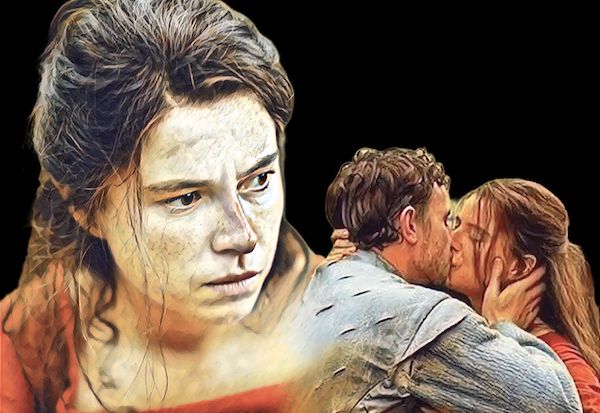

At the center of the narrative are two of Ireland’s most celebrated actors. Jessie Buckley (Oscar nominee for Best Supporting Actress for The Lost Daughter, 2021) plays Agnes with visceral intensity, while Paul Mescal (Oscar nominee for Best Actor for Aftersun, 2022) plays William Shakespeare, here seen more as an ordinary man than as an icon. Their chemistry, according to early viewers, sustains the story’s emotional force.

Young Jacobi Jupe plays Hamnet in a tender and painful performance. The cast also includes Emily Watson and Joe Alwyn.

The score is by Max Richter, weaving pure emotion. Known for The Leftovers and for post-minimalist albums, Richter created music for Hamnet that, according to Buckley, moved cast and crew to tears.

Early critical reception

The official premiere in Toronto will be on September 7, but critics who have already seen it describe a work of rare sensitivity, one that avoids the academicism of traditional biopics and instead bets on sensorial immersion: images of nature, the silence of grief, music as catharsis. It is seen as a strong contender in awards season, especially for the intensity of Buckley and Mescal’s performances and Zhao’s lyrical direction.

The connection between Hamnet and Hamlet

Historically, we know that Hamnet Shakespeare died in 1596 and that Hamlet was written around 1600. The two spellings were interchangeable at the time: Hamnet and Hamlet were common variations of the same name. More than coincidence, there is context. Shakespeare, having lost a son so young, soon wrote the greatest theatrical meditation on life, death, and memory. The Prince of Denmark, haunted by ghosts and obsessed with meaning, echoes a father’s grief.

O’Farrell’s novel, and now Zhao’s film, embrace that gap: the idea that Shakespeare transformed intimate tragedy into immortal art. There is no documentary proof, but there is more than enough poetry to convince.

Hamlet before Hamnet: the Danish prince

It is important to remember that Shakespeare did not invent the plot of Hamlet from nothing. His source was an old Norse legend recorded by Saxo Grammaticus in the 12th century, in Gesta Danorum. There we find the figure of Amleth, a Danish prince who feigns madness to survive after his uncle kills his father and takes the throne.

This narrative circulated in French adaptations in the 16th century, which Shakespeare likely read. In other words, there was indeed a “Hamlet” before Hamnet—Amleth, the legendary figure. But he was more myth than history, a mixture of chronicle and saga.

What Shakespeare did was take that folkloric base and, after losing his son, clothe it in grief. The Danish Amleth gave the plot its skeleton; Hamnet, the real boy, gave it flesh and soul.

What we have, then, is a triple fusion: the Scandinavian myth of Amleth, which provided the storyline of vengeance, ghosts, and feigned madness; the real boy, Hamnet Shakespeare, whose death in 1596 marked the lives of William and Agnes, and finally, the play, Hamlet, which united myth and personal grief, creating the greatest tragedy of English literature.

The theory that Hamlet is a direct homage to Hamnet is powerful and seductive. But, interestingly, other works by Shakespeare may echo the lost child even more clearly.

Specialists point to Twelfth Night, the comedy that presents a pair of twins—Viola and Sebastian—separated by a shipwreck. Each believes the other to be dead, a parallel to Hamnet and Judith, Shakespeare’s twins, separated forever by death.

More still, it is almost certain that Sonnet 33, one of the most melancholy in the collection, was written for Hamnet. In it, Shakespeare describes the feeling of losing something precious and inevitable, with images of clouds obscuring the sun. Many scholars read it as a veiled allusion to his grief for Hamnet, since when he speaks of the “sun”—in English sun, homophone of son—he is speaking of his boy:

“Even so my sun one early morn did shine

With all triumphant splendour on my brow;

But out, alack, he was but one hour mine,

The region cloud hath mask’d him from me now.”

Thus, the child is present in more than one corner of his father’s work: not only in the tormented prince, but in the comedy of separation and in the lyrical sonnets of loss.

All Is True (2018): another portrait of grief

Even before Maggie O’Farrell and Chloé Zhao, cinema had already explored this absence. In 2018, Kenneth Branagh directed and starred in All Is True, written by Ben Elton. The film is set in 1613, after the Globe Theatre fire, when Shakespeare retired permanently to Stratford.

There, he reunited with Anne Hathaway (played by Judi Dench) and his daughters, trying to rebuild bonds after years apart. The ghost of Hamnet hovers over everything: Shakespeare plants a garden in his memory and confronts old guilt. The cast also includes Ian McKellen as the Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s close companion.

All Is True is visually stunning, inspired by Baroque and Elizabethan paintings, but its tone is melancholic, contemplative, and almost an epilogue. It is not about creative glory, but about old age, fatherhood, and grief.

Compared to Hamnet, it shows the other extreme of pain: not the moment of loss, but the aging with it. O’Farrell’s novel (and Zhao’s film) speak of the immediate impact; Branagh speaks of wounds that never heal.

The mystery and the love for Shakespeare endure. If Shakespeare in Love invented a fictional muse to justify Romeo and Juliet, Hamnet offers another answer: the playwright’s heart was not only fueled by youthful passions but also by irreparable grief. The death of Hamnet is the loudest silence in Shakespeare’s biography.

Maggie O’Farrell’s book gave that silence words; Chloé Zhao’s film gave it images, music, and flesh. Together, they reconstruct not just the genius, but the family, the pain, and the love that shaped some of the greatest works ever written. And yes, the Oscar race is likely to include the film among the main categories. We shall see.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

Fascinating stuff. I had heard about Hamnet, but the way you draw parallels here is most compelling. I shall have to research this matter further. . .

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa