We live in a time when watching is no longer a passive act. Today, everyone is both audience and critic, narrator, producer, and even amateur historian. Nothing reaches the public without being immediately dissected, compared, praised, or torn apart online. The paradox is that this culture feeds on two extremes: on one side, the insatiable craving for stories labeled as “real,” “historical,” or “based on true events”; on the other, the passion for absolute fantasy—dragons, vampires, zombies, whole galaxies conjured out of imagination.

The middle ground, that of pure invention, grows increasingly narrow. The audience wants either to believe that what they are watching really happened or to escape so completely that the story becomes a total detachment from reality.

When History Becomes Spectacle

The Gilded Age is a perfect example of this new logic. Viewers don’t just watch the lives of New York’s high society; they go online to research genealogies, to compare which characters are inspired by real people, and which families actually existed. There is a double pleasure here—learning history, but also losing oneself in dramatized invention. Strikingly, no one objects when Julian Fellowes alters details, creates new characters, or reshapes situations. On the contrary, the blend of fact and fiction enriches the narrative.

The same happens with Peaky Blinders. The Shelby gang never existed exactly as portrayed, but they were loosely inspired by real criminals from early 20th-century Birmingham. As the series progresses, it weaves historical figures (like the villain of the final season, Oswald Mosley, the British fascist leader) into a fictional plot. This constant oscillation between documented reality and artistic license is precisely what sustains its appeal.

Vikings and its sequel, Vikings: Valhalla, take a similar path. Characters like Ragnar Lothbrok, Lagertha, and Leif Erikson live in a liminal zone between legend and history. Very little is known about them, and the show fills those gaps with creative imagination, inventing dialogues, motives, alliances, and battles that can never be proven. And audiences embrace it, because they want to experience “history” and fantasy simultaneously.

When Fiction Takes on the Weight of History

On the other side, purely fictional universes have come to be treated like sacred canon. House of the Dragon exemplifies this: though based on George R. R. Martin’s Fire & Blood—a book that is itself entirely fictional—every episode is scrutinized by fans demanding near-documentary accuracy. Small changes in dates, relationships, or personalities spark fiery debates. The same phenomenon governs Game of Thrones and, of course, Star Wars.

The contradiction is obvious: we treat fantasy as if it were fixed history. Dragons and Jedi are discussed with the same rigor as dynasties and real wars.

The Real Dramatized

Meanwhile, there is a proliferation of films and series that exist only because they carry the label “based on a true story.” True crime booms, biopics of musicians flourish, and political dramas multiply. Even Shakespeare’s life—about which we know almost nothing—becomes the target of speculation, with filmmakers interpreting his plays as autobiographical clues. It’s a cultural compulsion to turn art into confession, fiction into diary, text into testimony.

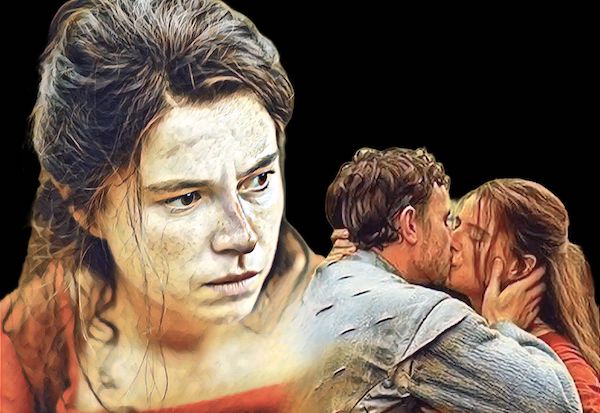

In this category, we also find the BBC’s King & Conqueror. Costume designer Margrét Einarsdóttir was clear: “It was never meant to be historically accurate.” The goal was not documentary but translation—making an era from a thousand years ago legible today. Costumes, colors, and textures become symbols: red as power, leather as female strength, blue turning to purple as a character nears the throne. It is reimagined history, fearless of distortion, because the aim is not dates but humanity.

The Audience’s Dilemma

Together, these examples reveal a deep cultural dilemma. We crave surprises, but criticize alterations. We want authenticity, but reject excess invention. We demand fantasy, but treat fantasy as if it were archival truth. At the same time, the label “based on true events” has become a seal of value—even when creative freedom stretches reality beyond recognition.

The True Work of Art

The result is that the show, the film, or the book is no longer the final product. The real contemporary artwork is the debate that unfolds around it. The Gilded Age inspires historical comparisons; House of the Dragon fuels endless disputes over fidelity; Star Wars lives perpetually in the tug-of-war between nostalgia and reinvention; Peaky Blinders and Vikings turn history and myth into a hybrid playground; King & Conqueror sparks reflection on the very nature of truth and invention.

And this is where social media comes in. Platforms like X, Instagram, TikTok, and Reddit are the new stages where these narratives expand. Episodes are live-commented, characters become memes, and creative decisions prompt petitions. Collective reception has become inseparable from the work itself. What was once just a series or a film is now also a forum, a battlefield, a mural of endless interpretations.

In the end, this may be the true spectacle of our age: the story exists, but what really matters is what we do with it—how we reinvent, critique, and remix it together. Fiction is no longer only on the page or screen. It lives in how we choose to experience, dispute, and rewrite our narratives in community.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.