“And thus the heart will break, and yet brokenly live on.”

— Lord Byron, Fare Thee Well (1816)

There is something profoundly symbolic in Guillermo del Toro’s decision to close his Frankenstein adaptation with this line by Byron. Written in 1816, in the midst of the poet’s painful separation from his wife, the verse was born from intimate sorrow. Yet it holds a universal truth: the heart may shatter, and still continue to live — fractured, but beating. This paradox, the endurance of something that can no longer be whole, connects Byron to Mary Shelley’s universe and to the creature she conceived in one of the most singular moments in literary history.

It was also in 1816, during the infamous “year without a summer,” that a small circle of poets and thinkers sought refuge at Villa Diodati, on the shores of Lake Geneva. Mary Godwin (not yet Shelley), Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, John Polidori, and Claire Clairmont gathered in an atmosphere thick with gloom. The eruption of Mount Tambora had plunged Europe into a season of darkness and storms, a mood that mirrored the apocalyptic conversations of the group. To pass the time, they read German ghost stories from Fantasmagoriana, and their discussions wandered from philosophy to galvanism, to the possibility of reanimating life itself. It was Byron who, eager for provocation, suggested a contest: each should write a tale of horror.

What emerged from that challenge changed literature. Polidori wrote The Vampyre, the blueprint for the modern vampire and a direct influence on Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Byron himself produced only a fragment. Percy Shelley tried but left no lasting piece from the game. And Mary, just eighteen, conceived something far greater than anyone expected.

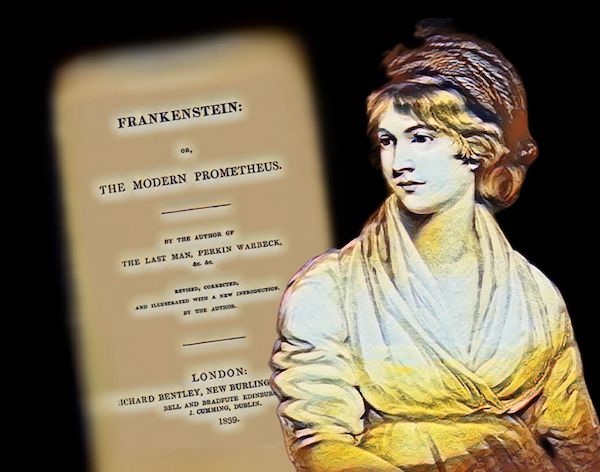

Haunted by insomnia and the weight of their debates, she experienced what she later described as a “waking dream.” In it, she envisioned a young scientist who, obsessed with piercing nature’s veil, assembles a living being from the dead. When the creature awakens, the creator recoils in horror. From that vision was born Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818).

At first, it seemed nothing more than a response to Byron’s challenge. But Shelley’s work transcended the moment. She fused Gothic dread with Romantic awe, and in doing so, she invented something entirely new: the beginnings of modern science fiction. Victor Frankenstein embodied the peril of knowledge without responsibility, the drive to create without considering consequences. His creature, meanwhile, became the mirror of human fears — at once monstrous and innocent, rejected not for what he does but for what he is. Like Byron’s line, the creature is condemned to live brokenly: shunned by his maker, cursed with loneliness, yet carrying within him the ability to love, to rage, and to suffer.

The impact of Frankenstein is immeasurable. Mary Shelley did more than outshine her companions at Villa Diodati; she gave literature a metaphor that still breathes. She opened the door to narratives that would explore man and machine, creator and creation, inspiring everyone from H. G. Wells to Isaac Asimov, from German Expressionism’s Metropolis to Universal’s horror classics, and even to today’s debates on bioethics and artificial intelligence.

It is striking that the same year Byron wrote Fare Thee Well, Mary gave birth to Frankenstein. Both works belong to the same Romantic moment: the sublime, the tragic, the endurance of what is broken. By ending his film with Byron’s words, del Toro weaves the two together — the broken heart and the rejected creature, both surviving in fragments.

Ultimately, Frankenstein is not simply Gothic horror, nor merely the first step into science fiction. It is a parable of human existence: our urge to create, our fear of what we bring forth, our cruelty in rejecting the other, and our uncanny ability to live on in ruins. Byron gave the words, Mary gave the narrative, and together, in 1816, they left us a legacy that still beats — however “brokenly.”

The film premieres in theaters in October, but arrives on Netflix on November 7, 2025.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu