Some ballets seem to belong to history, artifacts of a vanished world, and some ballets live as declarations, as manifestos disguised as choreography. Theme and Variations, created by George Balanchine in 1947 for American Ballet Theatre, belongs unmistakably to the second category. It is both a memory of the imperial Russia he left behind and a vision of what ballet might become in America. It is a monument built out of steps, variations, and crystalline geometry — a work that breathes at once nostalgia and modernity.

When Balanchine turned to the final movement of Tchaikovsky’s Suite No. 3, he chose not only music but history itself. The score evokes grandeur, imperial fantasy, and ceremonial majesty. In its cascades of variations and culminating polonaise, Balanchine heard an echo of Petipa, of the court ballets of St. Petersburg. Yet instead of recreating that past literally, he abstracted it. He distilled its essence into pure dance: no narrative, no decorous drama, just bodies tracing architecture in space, bodies becoming rhythm.

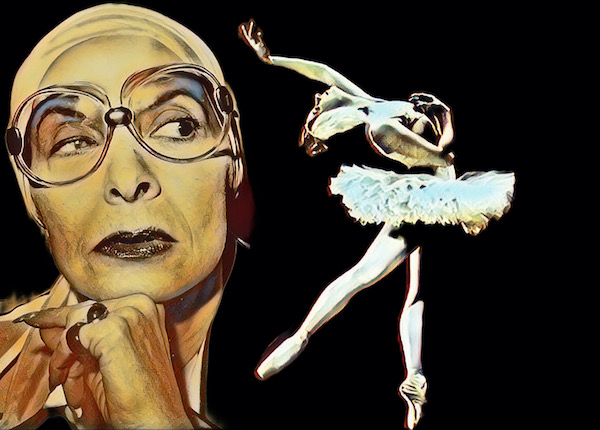

At its premiere, Alicia Alonso and Igor Youskevitch were entrusted with the mission of bringing the ballet to life. Alonso, already facing her progressive loss of vision, seemed destined for the role: she danced not only the movements but the stage itself, even the music, entirely by memory. Later, she would recall: “Technically, it was very difficult. I always have a good rhythm of breathing with my dancing, but at the end of the ballet, it is very, very hard. The air is not enough.” The challenge was not only physical but above all musical: there were passages where the rhythm of the choreography seemed misaligned with the rhythm of the score. “At the end of my variation,” she explained, “the steps took five counts when the music was in four. That meant I always felt I was late, that I had to hurry. It was very difficult.”

This kind of tension was deliberate. Balanchine liked to “play” with his dancers, proposing almost impossible difficulties. Alonso admitted: “It was a kind of game, at my cost, because he said he would make everything very difficult, and I would work and I would succeed. And this time, he really did it.” This game of provocations and challenges became a silent battle between them — a creative duel in which neither the choreographer nor the ballerina would yield.

“I danced with the music, but I was not conscious of the value of dancing the music. I had the feeling that for Mr. Balanchine, number one was the music, and number two, the ballerina. Once he told me that he didn’t see dancers; what he saw were the notes of the music dancing.”

— Alicia Alonso on George Balanchine and Theme and Variations

Alicia rejected the idea that Balanchine had built the ballet around her strengths, as some critics suggested. “He never worked with what was easy for me. He worked from his own inspiration. Always harder, harder, to see if we would give up. And I never did. I was very stubborn: if I had to do something, I did it. And I think he admired that.”

Her interpretation established the paradox at the heart of Theme and Variations: that absolute control and absolute surrender must coexist, that clarity of line must merge with ineffable majesty.

For any ballerina who attempts it, the ballet remains an ordeal. It is not only a technical Everest — though it is that, with its relentless succession of pirouettes, jumps, and crystalline steps — but also an aesthetic trial. To conquer it is not merely to display virtuosity; it is to embody majesty. The performer must appear to float above exhaustion, to radiate an authority that is not personal but archetypal. In this sense, Theme and Variations is not just choreography; it is ritual: the ritual of testing whether the classical tradition can still live, whether the imperial dream can be renewed through the body of a ballerina.

For Alonso, the result was a ballet that allowed no breathing space. Each solo presented not only technical variation but also facets of personality: “For me, each solo showed a different part of the ballerina. One was fresh, fast, and elegant; another had cadence, an adagio with the corps, more romantic; another was pure technical virtuosity. None of them was easy. But together they formed one continuity, one complete vision.”

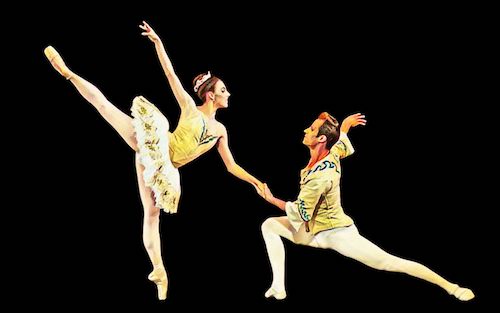

The final pas de deux, which comes immediately after the ballerina’s variation — reversing the traditional order — was especially punishing. “That was very difficult, because usually the pas de deux comes first, followed by the variations. Not here. I finished my variation and immediately had to go into the pas de deux. But he knew what he was doing. The way he choreographed, the way he played with the music, made us able to go on.”

This consciousness of music marked Alonso profoundly. Although she had always been a musical dancer, she admitted, “With him, I became conscious. I danced with the music, but I wasn’t aware of its value. He made me feel how each step belonged to each note, as if the musical phrase was the true motor of the choreography.” She even described how she associated movements with specific instruments: if she heard the trombone, her arm gained weight and impact; if it was a violin, she sought continuous fluidity.

With Youskevitch, she formed one of the most celebrated partnerships in ballet history. It was not merely stage chemistry but relentless work. “Even on tour, in cafés, on trains, in hotels, we were always talking about how to make it better. We tried a detail differently, adjusted the glance, the diagonal, the relation to the audience. We were never satisfied.” This constant dialogue turned Theme and Variations into something larger than the sum of its parts — an encounter between choreographer, dancers, and music, all striving to go further.

Regarding the critical reception, Alonso remembered with irony that Lincoln Kirstein, Balanchine’s historic partner, had once dismissed it as “not first-class work.” Her response was dry: “Perhaps he was in a bad mood. He was very intelligent; he knew when something was good, and this ballet was good.”

Time proved her right. Today, Theme and Variations is seen not only as a difficult piece but as one of the masterpieces of the twentieth century. Alonso herself justified its preservation simply: “I think it is a masterpiece. And I don’t think only those who saw it then, or see it now, have the right to it. The future has the right to see it.”

Over the decades, interpreters from Gelsey Kirkland to Natalia Makarova, from Paloma Herrera to Darci Kistler, have offered variations upon this theme of grandeur. Each has danced the steps; each has faced the trial. Yet the standard remains Alonso’s: not because she was flawless, but because she made imperfection part of transcendence. To dance Theme and Variations is always to measure oneself against that first apparition of impossible majesty.

If ABT was its birthplace, the ballet has long since outgrown national borders. It belongs now to New York City Ballet, to the Royal Ballet, to the Paris Opera Ballet, to the Mariinsky — to any stage willing to attempt its impossible purity. It is a global classic, one of Balanchine’s most enduring works, and one of the few pieces in the neoclassical canon that functions as both tribute and critique. Tribute, because it honors Petipa and the world of imperial ballet. Critique, because it strips that tradition of ornament and drama, revealing only the skeletal architecture of dance itself.

To watch Theme and Variations today is to witness a paradox. It is a ballet haunted by the past, yet it insists on futurity. It recreates the grandeur of a vanished empire, yet it insists that such grandeur can be reborn in America, in modern bodies, in new generations. It is a work that reveals the essence of Balanchine’s genius: his ability to transform memory into geometry, history into abstraction, and music into dance so exact that it seems inevitable.

More than seventy years later, the ballet has not aged. If anything, it has grown more austere, more impossible, more luminous. It demands of each dancer a confrontation with tradition and with the self, a willingness to step into history and to transcend it. To call it a ballet is perhaps insufficient. Theme and Variations is a dream of empire, a test of faith, and a manifesto for the future of dance.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.