To discuss revival is to discuss a profoundly human mechanism: nostalgia. Every 20 or 30 years, fashion, music, cinema, and literature seem to revisit their own archives, bringing back aesthetics and narratives that once defined a generation. But beneath the surface — flared jeans reissued, synthesizers revived, films and series reimagining classics — what truly moves is something more intimate: the collective desire to reconcile with the past and redefine our own identity.

The most evident explanation is psychological. Adolescence and early adulthood are periods of intense emotional formation. The songs we listen to then, the books we read, the films that move us — all of these inscribe themselves into memory with unique intensity. By the time we reach our 30s or 40s, we seek refuge in those symbols, which suddenly return as if time were a cassette tape rewinding. The cultural industry is aware of this and fuels the process: when a generation gains purchasing power, its past becomes a highly sought-after product. Marketing merely amplifies what is already inevitable, because the foundation is unconscious.

This movement explains why it is not uncommon to see parents and children united by the same band T-shirt or a rebooted series. Revival creates generational bridges: the adult relives their youth while the teenager discovers it as something new. The cycle sustains itself. There is also a dimension of psychological safety: in times of uncertainty, returning to what we know becomes a way of holding on to an emotional home. The 1970s aesthetic resurfaced in the 1990s, a time of political and cultural transformation. The 1980s returned in the 2000s, amid crises and technological transitions. Today, the late 1990s and early 2000s dominate runways, stages, and screens, in a world still processing the impacts of the pandemic, wars, and radical digital shifts.

In film and television, revival takes the form of remakes, sequels, and expanded universes. The very existence of endless franchises — from Star Wars to Marvel — responds to this impulse: keeping alive something once loved, updating its codes for new audiences, while simultaneously offering viewers more of what they already know. The sense of familiarity is comforting, but also a trap: how much novelty is truly offered, and how much keeps us tied to the familiar? Psychology shows that memory is not a faithful recording but a recreation. Revivals work the same way: they do not return the past as it was, but as we wish it had been.

In literature, the logic is similar. Reprints, adaptations, and reinterpretations carry the same impulse to retrieve and reinvent. Yet today, in the digital age, this process takes on a new layer. Cultural time seems accelerated. The 1990s have returned before they ever really “left.” Memes, playlists, and algorithms have shortened the distance between past and present. Streaming puts everything a click away: we can jump from a 1950s film to a newly released series in seconds. Revival, in this context, is no longer just cyclical — it becomes permanent.

This creates a contemporary paradox. If the cycle was once predictable — every 20 or 30 years, something would return — now we live in an expanded present, where all decades coexist simultaneously. A teenager today can dress like it’s the 1970s, listen to a vinyl record from the 1980s, binge-watch a 1990s series, and post it all on TikTok. Revival has ceased to be a generational gesture and has become a continuous language, shaped by algorithms that calculate our nostalgia before we can even name it.

At its core, though, the psychological need remains: we revisit the past to make sense of the present. Revival cycles remind us that identity is not a straight line, but a mosaic of times, sounds, images, and symbols that reappear whenever we need them. The market may turn this into a strategy, but the initial impulse is human. We long to meet ourselves again — and in doing so, perhaps reinvent who we are.

Revival in real time

Today, we are surrounded by signs of this process. In music, Britpop is back in the spotlight: Oasis has reunited after years of rivalry, Blur is revisiting its own trajectory, and Gorillaz is celebrating 25 years as proof that the turn of the millennium still pulses with life. Meanwhile, Y2K aesthetics dominate fashion, with low-rise jeans, metallics, and cropped tops returning to streets and runways.

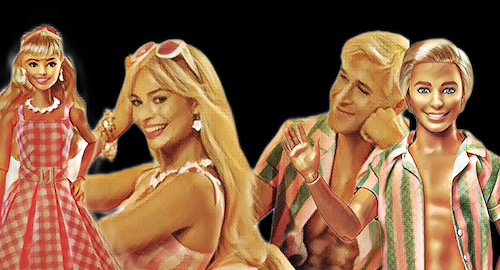

On screen, Stranger Things demonstrated how the 1980s could be resurrected with emotional force, creating new generations of fans, while Barbie (2023) reimagined a 1950s icon through a postmodern and feminist lens. The same applies to the wave of music biopics: Elvis, Whitney Houston, Amy Winehouse, and now Michael Jackson reappear in cinematic form, not just telling stories but offering affective reconciliations with artists who defined eras.

In literature, we see both reprints of classics in new formats and adaptations that rewrite entire universes — from Jane Austen retellings to the Dune phenomenon, which blends past and future in its new volumes and film adaptations. Literary revival is not simply about return, but about updating archetypes that continue to resonate.

These examples show that revival has stopped being a periodic “wave” and has become almost a permanent layer of our culture. Time, in today’s imagination, is not linear but simultaneous. We live in multiple decades at once, stitched together by desire, memory, and algorithm.

The future of revival

We may now be facing a moment where the traditional 20–30-year cycles no longer apply. If nostalgia once followed a predictable rhythm, today it is on demand. This could lead us into uncharted territory: the end of revival as return and the beginning of continuous nostalgia, happening in real time. What once reemerged decades later is now recycled instantly — often before it has even settled as memory.

This new cultural and technological era alters our relationship with the past. We may lose ourselves in a labyrinth of references, or, on the contrary, learn to live in constant dialogue with history — recognizing that culture no longer needs to wait decades to come back. It is always within reach, ready to be rediscovered.

And perhaps that is the most revealing truth: no matter how fast technology accelerates, the need to revisit who we once were remains the same. Revival is less about fashion, music, or film than about ourselves — about the eternal human desire to rewrite the past to understand the present, and thus, imagine the future.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.