When Amélie premiered in 2001, it felt like a gift to a cinema that had grown skeptical of fantasy. Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s delicate eye, the saturated colors, Yann Tiersen’s unmistakable score, and Audrey Tautou’s almost childlike charm turned the film into an improbable global success: more than $170 million at the box office, five Oscar nominations, awards in London and Paris, and Montmartre forever stamped as a tourist destination for those seeking the “Amélie café.” But more than numbers, Amélie became a language. A way of speaking about the absurdity of everyday life with poetry, irony, and tenderness.

It is curious, then, that Amanda Knox chose this very film as her favorite — and as the lens through which to tell her story. Acquitted in court but never freed from the caricature the media built around her, Knox lived through a grotesque spectacle: headlines that painted her as a femme fatale, televised trials that mattered more than the courtroom itself. What could have been framed only as tragedy became, in her eyes, an absurd fable. By invoking Amélie, Knox refuses melodrama, choosing instead a tone that is playful, almost detached — as if the only way to survive horror is to recount it as a story too improbable to be believed.

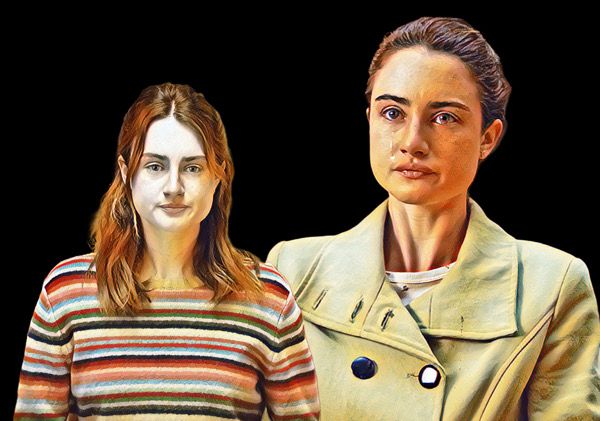

And this is precisely where The Twisted Tale of Amanda Knox tries (and fails) to follow her lead. There are inventive moments — symmetrical shots, color palettes that wink at Wes Anderson, and flashes of lyricism that recall Amélie’s eye for small gestures. Grace Van Patten, in the role of Knox, delivers a nuanced performance, balancing fragility and confusion, carrying scenes that might otherwise collapse under the weight of an uneven script. But the critics are right: the tone falters. The whimsical feels pasted over the tragic, and poetry too quickly gives way to artifice.

The deeper problem is imbalance. In its attempt to restore Amanda’s narrative, the series drains away context — Meredith Kercher remains in the shadows, and the institutional mechanisms that sustained the judicial farce are reduced to background noise. Instead of a reflection on media misogyny or systemic failure, what we get is a stylized retelling of a story already told too often, but rarely understood.

I agree with the critics: there is a lack of depth, a lack of courage to push beyond the surface. And that is what makes the comparison with Amélie even more striking. In the French film, it was the smallest details — a spoon breaking the crust of crème brûlée, a forgotten note, a shy glance — that revealed entire worlds. That is the gaze the series misses. Amanda Knox may cling to Amélie’s poetics to endure the absurd she lived through, but the adaptation forgets that to give meaning to horror, colors and framing are not enough. One must listen to the silences, give space to what was erased.

In the end, the irony is sharp: Amélie, a story about how small gestures can alter destinies, remains a more powerful key to understanding Amanda Knox than the very series made to tell her tale.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.