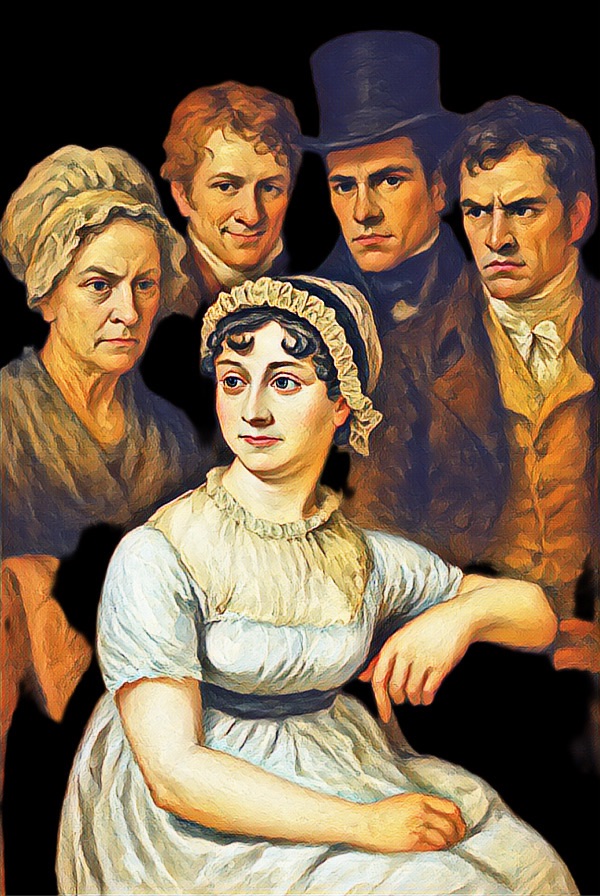

Jane Austen never needed Gothic villains or grandiose threats to create tension in her stories. Her antagonists are always much closer: neighbors, relatives, charming suitors, or authoritarian ladies who, with a polite smile or a gesture of arrogance, become silent obstacles to the love and integrity of her heroines. Instead of monsters, Austen gives us ordinary people, wrapped in the veneer of what society valued most in her time — wealth, charm, social position, politeness — but unable to sustain these appearances when confronted with truth.

What makes these characters so enduring is not explicit malice, but the way their masks gradually fall away. Each of them — from Wickham to Lady Susan, from Willoughby to the Crawfords, from William Elliot to General Tilney — reveals the same fundamental contrast: what appears virtuous on the outside, but proves hollow within. Austen, with delicacy and irony, does not destroy them with violence; she simply exposes them until only their essence remains. And in doing so, she goes beyond criticizing individuals: she unmasks an entire society built on fragile appearances.

Pride and Prejudice

George Wickham is perhaps the most charismatic antagonist in Pride and Prejudice. With smooth speech, distinguished looks, and undeniable charm, he wins Elizabeth’s trust and the sympathy of all Meryton. Yet his interest was never true love, but personal advantage, whether financial or social. Wickham’s downfall is not public ruin, but the revelation of his frivolity — when he seduces Lydia with no intention of marriage. At that moment, his mask falls, and Austen exposes the fragility of a man sustained only by appearances.

Lady Catherine de Bourgh, on the other hand, embodies the weight of hierarchy. Proud of her lineage and fortune, she sees Elizabeth as a threat to the order she considers natural: one where wealth and name determine destinies. Her interference in her nephew’s romance with Elizabeth is authoritarian and rude, but fails almost comically. The more she insists on imposing her will, the more she strengthens their union. Austen shows that aristocratic arrogance cannot resist the quiet power of integrity.

Mrs. Bennet, though not ill-intentioned, plays an antagonistic role for her daughters by embodying the most superficial side of social life. Obsessed with advantageous marriages, driven by anxiety about securing her daughters’ futures, her suffocating insistence creates embarrassment and reinforces prejudice against the family. Her downfall is symbolic: the more she speaks, the more she exposes her vulgarity before society. Austen portrays her with some affection, but makes clear that lack of decorum can be as limiting as aristocratic arrogance.

Lydia Bennet is, in herself, an obstacle. Her imprudence, vanity, and recklessness not only expose her to scandal but also compromise the reputation of all her sisters. Her interest is purely youthful: pleasure, dances, male attention. Her downfall — eloping with Wickham — is not only personal, but collective, affecting the whole family. Austen does not treat her cruelly, but shows how thoughtlessness could have devastating consequences in a society where female honor meant everything.

Mr. Collins, the obsequious clergyman, completes the picture. As an antagonist, he poses no real danger, but much embarrassment. His interest lies in securing social stability by marrying Elizabeth — a proposal made with such self-assurance it borders on absurdity. His downfall is immediate: Elizabeth’s refusal disarms his blind confidence. Later, by marrying Charlotte Lucas, Mr. Collins confirms what Austen criticizes with subtlety: marriage treated as a transaction, without affection or integrity.

Sense and Sensibility

John and Fanny Dashwood are the first antagonists of Sense and Sensibility, and their presence weighs heavily from the opening pages. Driven by cold self-interest, they reduce a father’s last wish to nothing. What should have been support for the Dashwood sisters becomes endless excuses to give them nothing. Their interest lies in preserving and increasing their own fortune, not sharing with those who, by natural generosity, most needed it. Their downfall is not scandal, but Austen’s characterization itself: a chilling portrait of a loveless marriage sustained only by selfishness.

Willoughby appears as Marianne’s perfect romantic ideal: handsome, witty, a lover of poetry and music, able to speak her language of sensibility. At first, his interest seems genuine: he flirts, charms, and shows tenderness. But soon his weakness and inability to withstand social pressure are revealed. By choosing a wealthy heiress over Marianne, Willoughby betrays himself. In their late reunion, his excuses sound sincere: he truly had loved Marianne, but could not sustain it against convenience. Austen does not absolve him — his punishment is to live in a loveless marriage, haunted by what he lost — yet she grants him a rare dimension among her antagonists: that of a repentant man, who once held happiness in his hands and let it go. This ambiguity allows interpretations of Willoughby not only as a villain but as a reflection of fragile and cowardly passions.

Lucy Steele is the calculating counterpart, cold where Willoughby is weak. Her interest is purely strategic: she traps Edward Ferrars in a secret engagement to secure her future, manipulating with false sweetness and an unsettling knack for intrigue. The shock comes when, realizing Edward brings no prestige, she transfers her affections without remorse to his brother. Her downfall is moral: in society’s eyes, her cunning may look like triumph, but Austen shows it is mere mediocrity, a victory without greatness. Lucy is not destroyed — she finds stability — but in the reader’s eyes, she remains small, reduced to a life built on calculation rather than feeling.

Emma

Emma turns the game inward. Frank Churchill, with his charm and secrets, deceives and entertains at others’ expense, but it is Emma herself who becomes her own antagonist. Her vanity, her conviction that she can direct others’ destinies, nearly ruins Harriet’s life. Her downfall is not public humiliation, but the painful recognition of the harm she caused. Austen, generous, does not destroy her: she allows Emma to grow and mature.

Frank Churchill is one of Austen’s most subtle and fascinating antagonists. Son of Mr. Weston, but raised apart in the wealthy Churchill household, he carries the mark of an indulgent upbringing. That indulgence made him witty, charming, and socially adept — but also accustomed to escaping consequences. His true passion is for Jane Fairfax, but, bound by their secret engagement, he masks it by diverting attention toward Emma. He hints, flatters, and plays, creating needless confusion that nearly destroys Harriet’s hopes. His “fall” is discreet: once the secret is revealed, his image of gallant wit collapses into that of a man who used charm to shield his own interests. Austen does not condemn him harshly — he still wins Jane — but makes clear that his charm was as deceptive as it was dangerous. He belongs to Austen’s gallery of seductive villains: not cruel, but capable of destabilizing hearts and narratives with a smile.

Emma Woodhouse, however, is the truest antagonist to herself. Wealthy, beautiful, and clever, she grows believing she can read and shape the lives around her. Her interference in Harriet’s affections, her manipulations and misreadings, all stem from vanity and self-assurance rather than malice. Her downfall is moral awakening: realizing she hurt Harriet and that her pride blinded her. Austen treats her with empathy, granting her the chance to change. Emma is thus a heroine-antagonist, a reminder that the greatest dangers often come from self-deception.

Mr. Elton, Highbury’s clergyman, at first seems a suitable match in Emma’s schemes for Harriet. But his real interest is Emma herself, for her fortune and status. His pompous, arrogant declaration in the carriage makes him an antagonist not only to Harriet but to Emma’s illusions. His downfall is immediate and moral: in exposing his opportunism, Austen makes him ridiculous, a man hiding vanity behind clerical decorum.

Mrs. Elton, his new wife, intensifies his antipathy. Recently enriched, lacking refinement, she seeks to dominate Highbury’s social life with condescension and ostentation. Her “fall” is gradual: every scene reveals her vulgarity, until she becomes the novel’s most detested caricature. Austen draws her with almost cruel humor, exposing pretension without substance.

Jane Fairfax is not an antagonist by design, but by contrast. Refined, reserved, modest, she embodies everything Emma is not: disciplined where Emma is impulsive, dignified where Emma is vain. Her quiet presence unsettles Emma, whose jealousy and coldness betray insecurity. The strain of her secret engagement to Frank nearly breaks her, a reminder of the harsh realities faced by women without fortune. Her “fall” is only apparent: the suffering of concealment and the humiliation of secrecy. Yet Austen preserves her dignity, making Jane a moral mirror through which Emma confronts her flaws.

In Emma, Austen weaves a constellation of antagonists — Frank Churchill, Mr. Elton, Mrs. Elton, and even Emma herself — each embodying a different failing: duplicity, opportunism, vulgarity, and self-deception.

Mansfield Park

Henry Crawford is one of Austen’s most complex antagonists. Handsome, witty, and naturally seductive, he treats flirtation as sport. His interest in Fanny Price begins as another conquest — a test of charm — but deepens into something more real. Many critics believe Henry truly fell in love with Fanny, drawn by her integrity and moral steadiness. But when she rejects him, his wounded vanity drives him into a destructive spiral, culminating in adultery with Maria Bertram. His inability to bear defeat shows the fragility of his feelings: he cannot sustain genuine love, reverting instead to the frivolity that defines him. His downfall is thus the revelation that charm without principle cannot endure reality.

Mary Crawford is more calculating. Intelligent, spirited, socially brilliant, she represents a world where appearances and convenience outweigh morality. Her love for Edmund Bertram is sincere, but bound to ambition: she wants him to rise, to embody prestige. Her downfall comes when she excuses her brother’s adultery as inconvenient rather than immoral. In that moment, she loses Edmund, and Austen shows that brilliance without integrity leads only to emptiness.

Mrs. Norris, Fanny’s aunt, is perhaps Austen’s most detestable antagonist. Petty, partial, and cruelly biased, she belittles Fanny while flattering the wealthy. Her interest lies solely in self-preservation within the family hierarchy. Her downfall is harsh: after Maria’s scandal, Mrs. Norris is cast out, condemned to isolation. Austen spares her no kindness, making her a biting caricature of meanness.

Sir Thomas Bertram, Fanny’s uncle, is ambivalent. Not villainous, but often antagonistic, his rigidity and blindness to his children’s flaws enable moral collapse at Mansfield. His interest lies in preserving order, wealth, and reputation, not individual happiness. He pressures Fanny to accept Henry, unable to see her values. His downfall is silent but heavy: the shock of watching his household unravel. Austen redeems him partially in the end, when he recognizes Fanny’s worth, but never hides how patriarchal severity contributed to the ruin.

Persuasion

William Elliot, cousin and heir, is Persuasion’s most direct and enigmatic antagonist. Polished, attentive, and impeccably mannered, he seems the opposite of Anne’s vain relatives: he listens, respects, and even appears to admire her intelligence. Perhaps there was some genuine admiration, a trace of affection for her steadfastness. Yet calculation always overrides any warmth. His aim is to secure his inheritance, prevent Mrs. Clay from marrying Sir Walter, and keep his position intact. Once exposed, his charm evaporates, and Austen shows that any affection he felt was hollow beside ambition. His downfall is the unmasking, a portrait of a society where even tenderness could be corrupted by interest.

Sir Walter Elliot, Anne’s father, is vanity incarnate. Obsessed with mirrors, titles, and lineage, he dismisses Anne’s worth and embodies aristocratic decay. His downfall is symbolic: trapped in his own arrogance, ridiculous rather than powerful.

Elizabeth Elliot, the eldest sister, inherits his vanity. She treats Anne as invisible, living only for social status. Her downfall mirrors her father’s: Austen does not punish her overtly, but leaves her confined to a sterile, loveless existence.

Mary Musgrove, the youngest sister, is not villainous but an indirect antagonist. Hypochondriac, self-centered, always craving attention, she drains Anne’s energy and eclipses her space. Her downfall is comic exposure: Austen portrays her as someone who never grows up.

Northanger Abbey

John Thorpe is the most obvious antagonist. Loud, vulgar, compulsively dishonest, he embodies everything Catherine Morland is not. His interest is shallow: Catherine’s supposed fortune and the chance to boast. His downfall is swift and ridiculous: Catherine sees through him, and he is dismissed as crude mediocrity.

Catherine’s imagination, however, is the novel’s truest antagonist. Steeped in Gothic romances, she projects murder and secrets into Northanger Abbey, mistaking reality for fiction. Her downfall is private and tender: the shame of realizing her fantasies were baseless. Austen does not ridicule her — she allows Catherine to grow, to mature into awareness and readiness for love.

General Tilney, finally, hovers between Gothic villain and pragmatic father. Austere and domineering, he appears menacing to Catherine, but his real interest is wealth and advantageous marriages. Welcoming Catherine under false assumptions of fortune, then expelling her upon learning the truth, he reveals greed and calculation, not monstrosity. His downfall is mild but clear: in the end, he must accept her marriage to Henry, proving affection stronger than control.

Lady Susan

Lady Susan Vernon is singular among Austen’s creations, for she unites in herself the brilliance and corruption that, in other novels, are spread across many characters. A beautiful, witty, intelligent widow, she manipulates everyone with calculated coldness. Her interest is never love, but advantage: a suitable marriage for herself, and ridding herself of responsibility by forcing her daughter into a detested match. Her letters reveal razor-sharp irony and full awareness of her deceit. Her downfall is relative: she is not ruined, but ends in a lesser marriage, still clinging to her mask of triumph. Austen, in this biting satire, shows what happens when calculation and manipulation form the core of a character. Lady Susan is antagonist to all — her daughter, her rivals, her lovers — and protagonist of her own tale.

The antagonists of Jane Austen — from Wickham’s charm to William Elliot’s calculation, from Lady Catherine’s arrogance to Mrs. Elton’s vulgarity, from Lady Susan’s manipulation to General Tilney’s cold pragmatism — share a common essence: figures polished on the outside, yet fragile in integrity. They embody what society prized: wealth, beauty, charm, and position. But in Austen’s hands, the veneer always cracks.

Their downfalls are not thunderous punishments but moral unmaskings. Wickham is not crushed, only revealed. Willoughby is not ruined, only trapped in emptiness. Henry Crawford cannot redeem himself. William Elliot loses credibility. Lady Susan shrinks into a smaller destiny. Austen never shouts, never brutalizes — she simply lets the masks fall under quiet light.

With irony and empathy, she sketches human flaws. Her antagonists are not monsters, but ordinary people, driven by vanity, selfishness, fear, or convenience. That is why they endure: because they force us to recognize, beneath polished surfaces, the universal tension between appearance and truth, calculation and affection, convenience and integrity.

In the end, Austen reminds us that her true heroes and heroines prevail not through force or splendor, but through constancy of character. Integrity, in her world, is always the greatest triumph — and her antagonists, in their silent downfalls, reveal just how rare, precious, and revolutionary that virtue truly is.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.