There are pieces of music that become larger than the score. Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings and Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight belong to that rare category where emotion is so universal that the work itself becomes almost synonymous with grief, loss, and contemplation. It is impossible to listen to either one without feeling a lump in your throat — and perhaps that is why cinema and television have adopted them as definitive soundtracks for human sorrow.

The Melody of the Impossible: On the Nature of Daylight and the Weight of Emotion

Among all of Max Richter’s creations, On the Nature of Daylight holds a singular place. Written in 2004 for the album The Blue Notebooks, the piece began as a meditation on violence and political emptiness; yet, it has transcended decades to become one of the most recognizable voices of melancholy in film and television. It is impossible to hear it without feeling that knot in the chest that only music can provoke.

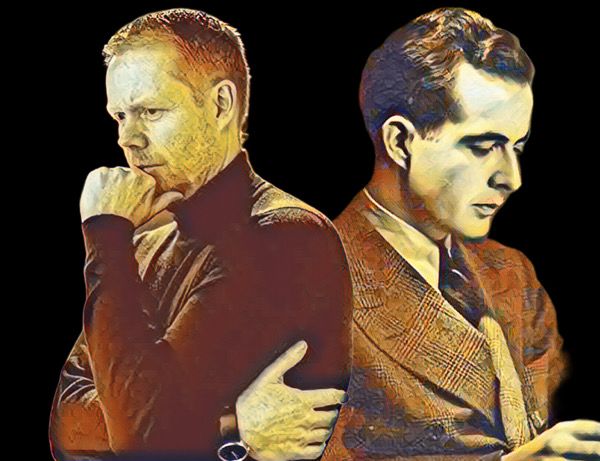

The inspiration came from Richter’s desire to translate the silence of grief into strings — not a grief that roars, but one that settles in slowly, like an absence. Perhaps that is why it is so often compared to Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, another piece that has endured through time as a synonym for mourning and beauty. Barber wrote in the 1930s; Richter, at the dawn of the 21st century. Both, however, seem to wrestle with the same question: how can music give voice to what cannot be said?

Unsurprisingly, On the Nature of Daylight has become a recurring soundtrack in moments of great emotional weight. Martin Scorsese used it in Shutter Island (2010), heightening the sense of intimate tragedy. Denis Villeneuve placed it at the heart of Arrival (2016), where time and loss merge into an inevitable tenderness. The series The Last of Us also drew upon it to underscore one of the most devastating passages of its first season, confirming that the piece has become an emotional code understood everywhere.

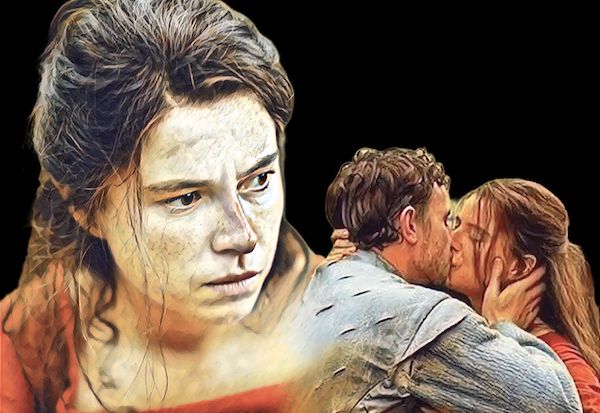

And now, in 2025, the music strikes us again in Hamnet, Chloé Zhao’s film adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s novel. If there were any doubts that the composition might grow stale, listening to how it fits into this story of Shakespeare and the grief over a child’s death makes it clear: however often repeated, On the Nature of Daylight never fails to break our hearts. Each time it appears, it doesn’t merely accompany the scene — it becomes the scene.

This, perhaps, is Richter’s greatest achievement: crafting a piece that, even after countless reuses, never loses its power to wound us gently. It is the music of the impossible: turning pain into beauty, and beauty into pain, in an endless cycle.

Barber and the Cry of the 20th Century

Samuel Barber composed Adagio for Strings in 1936, and the work soon became the funeral hymn of the 20th century. Played at U.S. presidential funerals and in ceremonies of collective mourning — including after the September 11 attacks — the piece acquired an aura of public solemnity.

Its impact in cinema was just as defining. Oliver Stone used it in Platoon (1986) to intensify the horror of the Vietnam War, while David Lynch placed it in The Elephant Man (1980), underscoring the tenderness and sorrow of a man living on the margins. On television, it appears in documentaries and memorial events whenever the need arises to summon a sense of national tragedy or irreparable loss. The Adagio is the collective cry: music that does not belong to any one listener, but to humanity itself.

Richter and the Sigh of the 21st Century

Max Richter, decades later, wrote On the Nature of Daylight with a similar intent: to carve out a space for contemplation in the face of emptiness. But instead of Barber’s romantic grandeur, Richter relies on minimalism. Repetitive strings, gentle variations, restrained pacing — all arranged to produce not a cry, but a sigh.

In contemporary cinema, the piece has become ubiquitous. Scorsese, Villeneuve, and Zhao have chosen it for moments of intimate revelation, while television has turned it into an instant trigger of emotion. The Last of Us, in particular, secured its place in pop culture by using it in “Long, Long Time,” the farewell of Bill and Frank set against perhaps the most devastating melody imaginable. Richter has become the musical voice of 21st-century grief: quieter, more private, but no less universal.

The Dialogue Between Barber and Richter

To compare Barber and Richter is not only an aesthetic exercise, but also a historical one. Adagio for Strings is the monumental lament of the 20th century, capable of translating wars, tragedies, and national mourning. On the Nature of Daylight, meanwhile, is the sigh of the 21st century: intimate, minimalist, written for personal narratives that take on collective meaning through the screen.

One is the cry of an era marked by world wars and ideological battles; the other is the quiet ache of a fragmented time, where violence is diffuse and pain surfaces in smaller stories. Yet both belong to the same spiritual lineage: music that accompanies us when words fail, beauty that rises out of the wound.

Perhaps that is why, when we hear Richter, we inevitably think of Barber. Two composers separated by decades, yet united by the same impossible ambition: to transform the unspeakable into sound.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.